The Bluffer’s Guide to Sake

Sommelier and co-owner of Blackmarket Sake Matt Young talks us through the rice brew.

Ichi, ni, san — SAKE BOMB! Remember how that night ended? Me neither. Or maybe you prefer some kind of lychee-infused-sake cosmo situation. But the elusive Japanese speciality of sake is more than capable of standing alone, as Black Market Sake co-owner Matt Young explains to Concrete Playground.

Young and co-owner Linda Wiss started the groundwork for Black Market Sake some five years ago while they both worked at Sydney's Aria. Today they import from about 16 Japanese producers and have a standout reputation. And Australia's having a burgeoning love affair with sake; we are now the second largest sake importer, behind the United States, and can boast an impressive annual growth rate of 12 percent in the market.

But let's set the figures aside and get you brushed up ahead of Sydney's next drinking trend.

What is sake?

C'est simple! It is a Japanese alcohol brewed from specifically grown rice, water, yeast and koji-kin. But, in the great tradition of Peking duck and Mumbai vs. Bombay, we have a few things to clear up. Firstly, sake just means booze in Japanese, and while that was once near-exclusively what we call sake, in the modern era of Japanese whisky, beer and wine the locals call it Nippon shu, meaning Japanese drink. Our next erroneous assumption is rice wine — this Western shorthand ignores that being brewed from a grain not from fruit makes sake closer to beer than wine, and its booze content puts both to shame, with most sakes coming in just under the 20 percent mark.

Wait, koji-kin?

Koji-kin is the magical ingredient, which is very unique to Japan and it is what helps break the starch in the rice down into sugar — so the sugar is then fermented into alcohol. It is also used in the production of many other products, notably soy, mirin miso and so on. It is a kind of mould, but the good kind, Young is quick to explain, "like the kind you find in cheese". He even likens the glossy texture koji-kin gives the rice to Camembert cheese.

Is it big in Japan?

Sake consumption within Japan has steadily decreased over the last hundred years; the number of breweries has halved since the 1970s to about 1500 today, and it did the same from the 1930s to the '70s. "The consumption in Japan has been on the slide for a long time. The younger generation got into beer and whisky and gave up on sake as an old man’s drink."

Does sake exist outside of Japan?

Production of rice-wine started in China and — along with Korea — it is still made today. However, in both instances large quantities of additives and distilled alcohol go into the product. “So, Japan has the most refined drink — although you can trace it back to the Chinese.”

What's in a name?

Sake menus have an anxiety causing reputation amongst even the most seasoned diners, and a lot of that is due to their lengthy naming system, but the truth is all the information you need is right there in front of you. "The more words that are on the label the less has been done to the product — so no charcoal filteration (muroka); not-pasteurised (namazake) that sort of stuff is always on the label, but if they do it than there won't be anything on the label,” says Young.

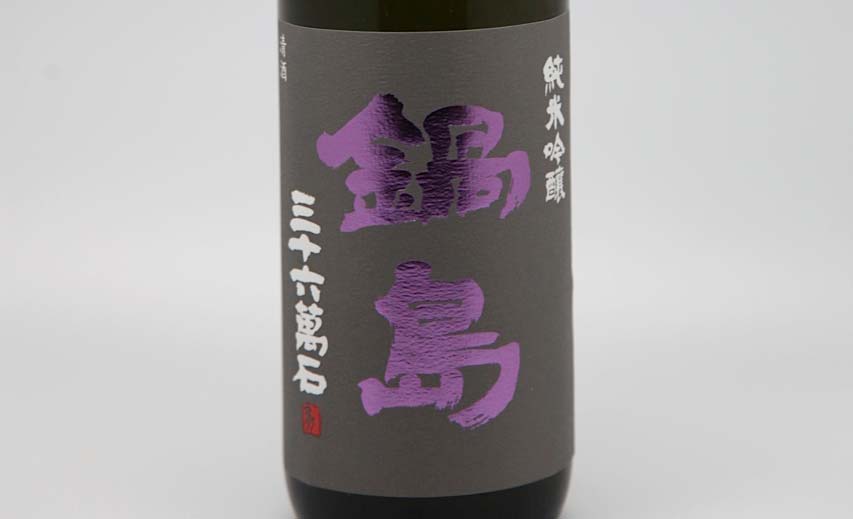

Here are a few keywords to help you unlock a sake list, first up: junmai. This is your producer telling you that they have made a pure sake, i.e. no distilled alcohol or flavour additives went into the brewing process. Some 80 percent of sake made in Japan fail this first test and are categorised as futsu-shu, which is essentially an inferior, cheaper drink.

The next consideration is how much they polished the rice, in layman terms: as you remove more of the grain; the more expensive the sake becomes. “The more you polish away the more aromatic it will be, the less you polish away the more kind of palate weight (it will have) and (the more) textural it will be.” The most polished sake is called daiginjo, where at least 50% of the rice has been removed and then ginjo comes in at least 60%.

(For a full list of common sake terms check out the glossary on the Black Market Sake website.)

How do I spot a good sake?

"Quality for me in sake is balance and complexity on the palate," says Young. "Often you'll see sake that is quite fragrant and elegant and pretty, but it doesn't have a lot of texture or weight on the palate, and coming from a wine background I prefer that more textural sake. So something that has lovely balance a little bit sweetness and something that finishes dry — evenness when you taste it.”

Characteristics he finds more dependent on the skill of the toji (master-brewer) and the quality of the ingredients than whether 70% or 60% of the grain has been removed. Hiroshima, Kyoto and Chiba are all top sake-producing regions.

Which cuisines match well with sake?

Other than the obvious, "French techniques have a lot in common with sake," says Young. So, consommes and broths are easily matched, while more robust sakes (ask for spice and high levels of acidity) stand up to heavier dishes like braised pork. But, if you want to hear Young wax a little lyrical, mention the marriage of cheese and sake. To spite the well-worn tradition of cheese and wine, this sommelier pairs Swiss mountain cheeses, parmesan and other hard cheeses with the Japanese beverage (to apparently elating effect). Also, try a dark chocolate match, as per Young's suggestion.

Hot or cold?

“The Japanese believe that every sake has a sweet spot, and that could be chilled, room temperature or warmed," says Young. "And when we say warmed, we mean gently warmed, 'cause you don't want to boil it but heat it to body temperature, essentially.”

That being said, there are two reasons heating sake became popular. Quick warning: it is embarrassing if you never guessed reason A. Japan is a cold country, and sake breweries are generally about 4-5°C (brewing often takes place in winter — fun fact), so sake brewers would heat up their knock-off sake to heat them up. Similarly, when sakes have had alcohol, sugars and enzymes added to them (remember that is 80% of sakes), there's nothing like a bit of gentle heat to mask the inferiority of the product. For those playing at home, that means futsuu sakes are likely best served warm, while unpasteurized sakes are almost always best chilled.

When is sake traditionally drunk?

The short answer is all the time, but Young notes that in Western culture it has garnered a reputation as an aperitif (that's before the meal, guys).

Where to enjoy sake in Sydney?

Momofuku. Although Young concedes the food is pretty good, too.

Top image, What is sake image, Koji-kin image, How do I spot good sake? image and What's in a name image courtesy of Black Market Sake.