Following Up Hottest 100 of Australian Songs Success with a Second Documentary About Your Life and Career: Jimmy Barnes Talks 'Working Class Man'

This iconic Australian rocker has been soundtracking the nation for more than half a century — and, of late, finding catharsis through working through his past on the page and on-screen.

Much that Jimmy Barnes has uttered, sang and screamed is immortalised in Australian history. His discography, both as the lead singer of Cold Chisel and as a solo artist — and via his many collaborations — has echoed across the nation and soundtracked this sunburnt country since 1973. "Oh, my soul" now ranks up there. Those were the three words that he exclaimed to Triple J announcers Zan Rowe and Lucy Smith when he heard live on air that 'Flame Trees' had come in at number seven in the first-ever Hottest 100 of Australian Songs — a chat that he was doing because 'Khe Sanh' had just placed eighth. Australia demonstrated their appreciation for Barnesy's contribution to local music with their votes, including for 'Working Class Man' at number 56, and he clearly, audibly, emotionally appreciated that love in turn.

"We've had a lot of awards and all that sort of stuff, and big claims to fame over the years, and we've always been a bit 'nah, you can't say this is the best song ever', because everybody has their own taste," Barnes tells Concrete Playground. "But for me, the best thing about that top 100, the top 200 even, was the fact that a radio station — which Cold Chisel literally helped start, we were playing when they were Double J, Live at the Wireless, when it was a scrambling little station, we helped get them set up — but there's a station that's become our national carrier, that is the only really, truly national radio station for kids in this country. And there's times when I listen to it and I go 'I don't get it. I don't really get what you're playing here', but they're the only station that still plays a load of Australian music. And the fact that on that day they celebrated Australian music and played 100 Australian songs, which were a collection of songs that had moved and affected the punters in this country — just to be a part of that was a good thing for me, and to be a part of that group of songs."

Barnes himself joined in with selecting his favourites, entering his picks in the poll. "There's a lot of great songs in this country. I voted for 'Eagle Rock' myself," he advises. He's passionate about shining the spotlight on Aussie tunes — "it's very cool. And the thought that they were celebrating Australian music was the best thing ever. That was the best part about it. I think they should do it more often," he offers — and also equally as enthusiastic about the fellow local acts that earned a place in the countdown.

"You look at that that top five or whatever it was, whether it's INXS' 'Never Tear Us Apart' — I think that besides it being a great song and beautiful film clips and all that, we have that loss, that sad loss of Michael [Hutchence], who was such a dear soul and just a magnetic frontman. The band were just unique the way they played, and they couldn't play it like that without Michael. So there's a tragedy to it," Barnes continues. He collaborated with INXS on 1986 single 'Good Times', which featured on The Lost Boys soundtrack.

"You have The Veronicas, who are these little intense pop girls who are just incredible," Barnes says. "They were all from different worlds. There was all sorts of stuff. There was Kylie. There was all sorts of stuff in the top 20, it was so eclectic and so mixed that I just thought 'I'm glad to be a part of that group of songs, doesn't matter where I am in the chart as long as we're in amongst it all, then it's a good thing'. There were acts with more songs than us, but it wasn't that sort of competition. It was just great. I'm listening to the top 100 and I hear Jet come on with 'Are You Gonna Be My Girl' and I go 'what a great song. Jesus, who wrote that? That's really cool'."

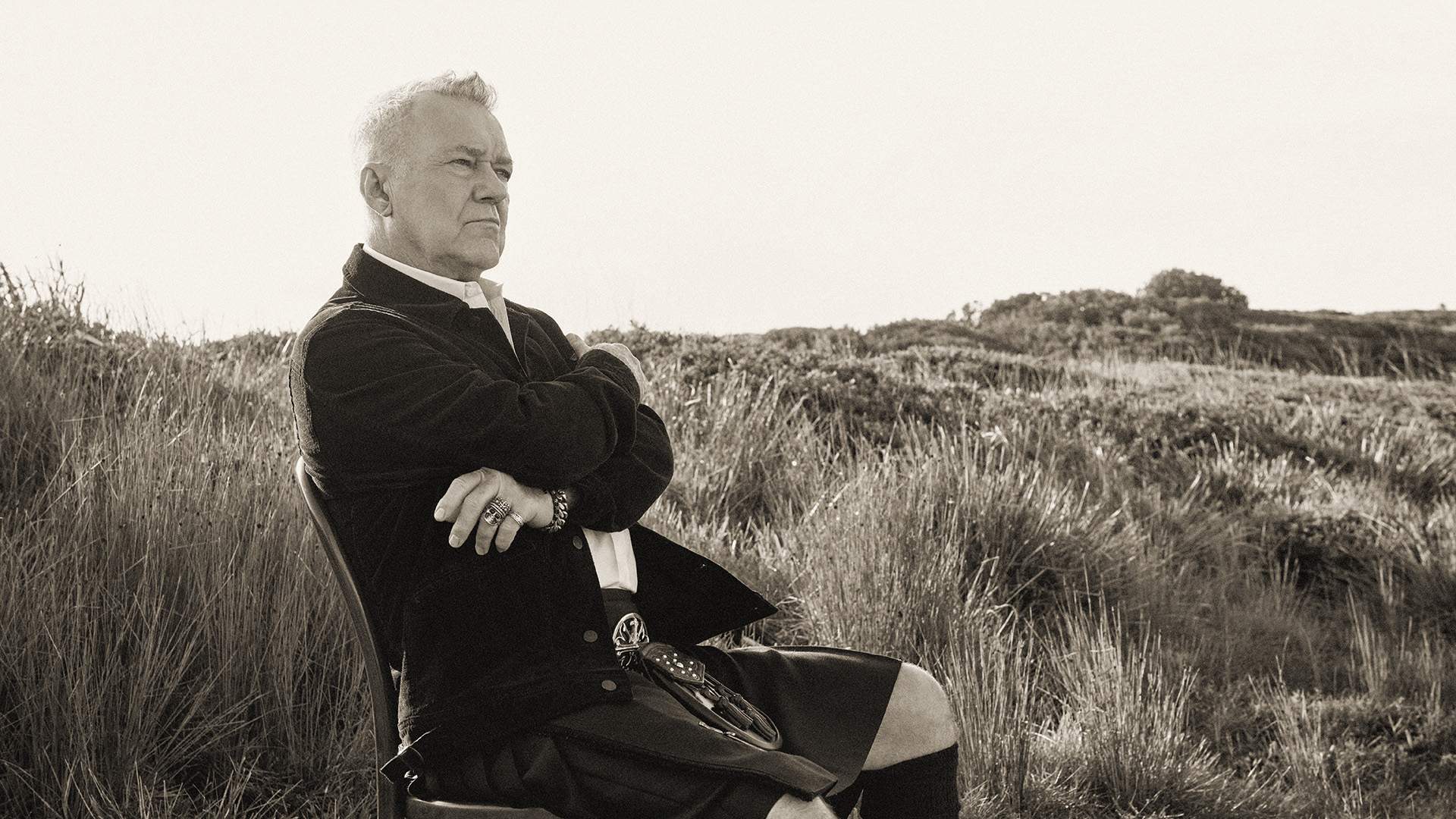

Sam Tabone/Getty Images

Long before the country spent a day revelling in the best 100 Aussie tunes — and a week afterwards enjoying the next 100, too — Barnes was already in deeply reflective mode. Almost a decade ago, in 2016, he released his first memoir Working Class Boy, which saw the rocker lay bare his traumatic childhood. Focusing on his adult years, Working Class Man as a book hit shelves the following year. 2018 then brought Working Class Boy to cinemas as documentary, premiering at the Melbourne International Film Festival. Now, seven years later, Working Class Man is also a film and also debuting at MIFF. Between the page and the screen, Barnes has taken his excavation of his upbringing, life and career to the stage as well.

Australians have been embracing Barnes on every step on this journey. In their printed guises, Working Class Boy and Working Class Man both became bestsellers, and each also won the Australian Book Industry Award for Biography of the Year. Crowds flocked to see Barnes talk about his experiences live. Viewers did the same with the first doco, which notched up a spectacular array of feats at the time. It played on the largest amount of screens, 220, for an Aussie doco; took over $500,000 in its opening weekend to top that period for a local documentary; and it scored the biggest opening for a doco in Australia since This Is It, 2009's Michael Jackson concert film.

James Gourley/Getty Images for TV WEEK Logie Awards

As a movie, then, Jimmy Barnes: Working Class Man is a highly anticipated sequel. With Andrew Farrell (How Australia Got Its Mojo) in the director's chair after executive producing Jimmy Barnes: Working Class Boy — which veteran filmmaker Mark Joffe (Spotswood, Cosi, The Man Who Sued God) helmed — it traces the impact of a childhood of neglect, abuse and poverty upon Barnes as he became a rock star, all as it charts his time behind the microphone from joining Cold Chisel onwards. In the film and in conversation chatting about it alike, the man who'll also be forever known as the voice of 'Breakfast at Sweethearts', 'Choirgirl', 'Cheap Wine', 'You've Got Nothing I Want', 'Saturday Night', 'No Second Prize' and so much more is candid as well as relaxed, even about the darker days that he's been unpacking in his memoirs and their documentary adaptations.

"All that stuff was pretty raw and fairly emotional, but because I've been through writing the book and obviously the process of, I guess, detraumatising myself from it all over the few years after that, and then going through the Working Class Man spoken-word tour, which we based this doco on, it gave me time to process it all," Barnes notes. "So there's stuff there that every time I look at it, I go 'ouch, I wish I could have not done that', but I've learned to live with everything I've done."

Daniel Boud

Of Jimmy Barnes: Working Class Man, he says "they've done a fabulous job". Of Farrell: "we've known each other for a long time and I trusted him completely with it". That act of reflecting the past has also been driving some of Barnes' live tours, with Cold Chisel taking to the stage around the country to mark their 50th anniversary in 2024, and the 40th anniversary of 'Working Class Man', the song — and album For the Working Class Man that it's on as well — the reason for his next tour in November 2025.

Barnes is currently as prolific as ever: alongside the new documentary and the two tours mentioned above, he opened the 2025 Logies, June was all about his Defiant tour, he's released seven albums in the past decade as well as six books so far, and has his second recipe book with his wife Jane, Seasons Where the River Bends, hitting stores in October. From whether he had any inkling that his memoirs would strike such a chord, their leaps to the screen and how he feels about his part in inspiring men to be emotionally open in a way that isn't usually part of Aussie masculinity, through to everything in his life being a family affair, boasting a catalogue of songs that's engrained in Australia's identity and his career longevity, we also spoke with the icon who'll always be known as Barnesy about plenty more.

On Whether Barnes Had Any Idea of What Might Follow Working Class Boy — and the Impact That It Has Had Personally

"No, not really. But I did get a feeling pretty soon after I wrote it — it was so liberating to sit and write the book. It was something, at the time, doing it was very painful. And every day I wrote — this is the first book — every day I wrote, it would open up a new can of worms that I had to deal with. And there was obviously a lot with childhood trauma. There's a lot of stuff you just block out, and you forget details and all that sort of stuff.

And so I'd be writing it and then I'd remember all the stuff that I hadn't thought about for 50 years, 40 years or whatever. And it'd come back to me, and I'd have to process it and deal with it.

So the during the process of it, it was sort of a heavy time, a heavy burden on my shoulders. But every day I'd end up and I'd feel like something has been lifted off. And most days I'd finish writing, and I'd ring up my therapist and talk to him about stuff, and then he'd put more weight back on my shoulders and tell me more things to look for.

Jess Lizotte

So the process of doing that, it was dark and hard to deal with, but it was also enlightening at the same time. And so by the time I'd finished the book, I just felt that I'd learnt a process, a way to process the past and my childhood, without having to sit and actually not physically allow it to overwhelm me. I could do it and walk away from it and process it a bit and breathe, and come back and then write again. And every time it got too overwhelming, I could stop.

So I learned how to process — and that went along with a lot of help that I got from various psychotherapists and rehabs and all that sort of stuff. I had enough tools to be able deal with it. So I really enjoyed it. In the end, I really enjoyed the process of writing.

And that made me just think — I'd sort of half-written Working Class Man while I was writing the other one. The thing was, the publishers and everybody that was on the commercial side of the book was really wanting the rock 'n' roll, sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll story. And I'm going 'I think this is much more important for me to write, that I write the first one first'.

And so when I did it, I wasn't going to sit down and write about sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll, and brag about being wild and all that sort of stuff — because a lot of that stuff, it just is what it was, but a lot of it was as painful as when I was a child. And by the time I finished writing the first book, I realised that my behaviour as an adult, which I obviously, as I say in the book and on the show, I take full responsibility for, but it was heavily influenced by that trauma and that stuff that I just dealt with in the book previously.

So it gave me an opportunity to to look at not only the mistakes my parents made and the mistakes that we made as children, how we were brought up and all that sort of stuff, but also how that affected me and how I moved on as an adult, and how the impact of childhood trauma kept knocking on the door — it kept, every time I'd get over one thing, something else would reveal itself until it became so entwined with addiction.

And you turn into the parents, and I ended up with the same problems as they had, because I hadn't really — before I'd gotten that heavily into alcohol and drugs and that, I hadn't dealt with any of this stuff. So it was interesting. It was a really good process.

Jess Lizotte

And the other thing I liked about it was I could sit sitting down after spending years of singing, going out on stage and literally reaching out to people and going 'look at me, look at me, look at me', I could sit — writing books I'm sitting at a desk and just going back into my mind. It gave me a lot of freedom to, like I said, to not cherry pick but go in and look at things and get out of there before it was too heavy.

And it allowed me to do the same with my imagination. When I started writing fiction or more towards fiction, I just found it was really enjoyable. I could sit in my own head and just disappear into my own worlds there. So writing that first book has opened up this whole new, not career, but a new chapter in my life — no pun intended — that I really enjoy.

I can still go out and make music and feel that emotional response with people, or I can just bury myself in my own head and dig out stories, which I really enjoy almost as much as singing."

On What It Means to Barnes to Help Inspire Men to Be Emotionally Open in a Way That Isn't Usually a Part of Aussie Masculinity

"Well, it wasn't something that I did myself. It was the start of real growth of men. We'd all been brought up, everybody that I knew had been brought up, with 'men don't cry' and 'you've got to hold your emotions in' and 'don't you don't admit you're wrong', all that bullshit.

And I think part of that was just — like when my parents, when my dad was alive, he had to be strong just to survive. He was fighting. He was a prizefighter. My grandfather was fighting bare knuckles in the alleys of Scotland so that he could feed his family, and they had to be tough. They couldn't cry. They couldn't let people know they were weak. But I could look back on them though — and now I remember how scary my grandfather was, I thought he was very scary and that whole image I built up of him was scary — but I look back at it now and I think 'he's probably the same as me, just terrified the whole time'.

I know I spoke to my brother John about it — John was a dangerous guy, he was wild and he could fight like hell, and him and I spoke about it. And he said 'I only fought because I was so scared, and I had to be hypervigilant, hyperaggressive. I had to win because I didn't want to be hurt'. And I realised that they were like that.

So I guess writing these books, I was never looking for blame, to blame anybody, but in the process of writing them, there were times where I was really angry with my parents and angry with my family and all that sort of stuff. And in the process of the first book, I got angry. With the second book, I realised that I fell into the same patterns and I fell into the same traps, and I was trying the best I possibly could but it just wasn't good.

And so I learned about forgiveness for my parents in the process of writing those first two memoirs."

Sam Tabone/Getty Images

On Sharing Barnes' Story, and the Path to Working Class Boy and Working Class Man Receiving the Documentary Treatment

"I realised when I started writing Working Class Boy, in the process of writing, I realised that my story wasn't that unique to me. It was a common story that a lot of people went through. A lot of people went through the same things as me. And that was one of the reasons why I put the book out.

When I was first started to write, I was thinking I'd just write and when it's all finished, I could burn it and that'd be okay. It'd have done its job. But everybody I let have a look at it went 'oh, I can relate to this. I can relate to that'. And I realised that there were people who were going to be touched or see themselves in it, and maybe get a window of hope from it.

And so I wanted to film the shows — and one of the reasons I wanted to film the shows was because every night, when I go up and talk about all the stuff that I had written, something else would reveal itself to me. I'd be up there talking about my mum being angry and storming around and dragging us through the streets and stuff, and then I go 'oh geez, I remember this now'. I'd remember something else that she did.

There was a point where I remembered, I realised that as scary as my mum was, and as wild and all that sort of stuff, and she neglected us, but actually I realised that the only time I ever felt safe was when she held me in her arms, when I was a baby, when I young. And I realised that and I thought 'oh, man, all of this stuff, I've just kept thinking all the bad stuff. You've got to remember the good stuff, too'.

So things would reveal themselves as I wrote them. And I thought — and doing the stories, more would reveal, more detail, I'd think of more things. There's times when I'd be telling the stories — so it's sort of half-rehearsed, but I got pretty good at it after the first ten shows or so — and then suddenly I'd be telling the story and all this new stuff information would come to me. And so it was really, I wanted to film the shows then, because I wanted to see how far that went and see if it could — I didn't know how, if it was going to be a documentary or a movie or what we were going to do with it, it was more to have in case I needed it as another tool to deal with my own shit."

Jess Lizotte

On Ensuring That the Documentaries Were Always the Films That Barnes Was Comfortable With — Including No Dramatisations

"Mark was a dear friend of mine, and I love Mark's work as a filmmaker, anyway. I've known him for a long time. And one of the deals we did when he said he wanted to make it, one of the deals we made was that it had to be the story we wanted to tell. It wasn't going to be glamorous or dramatised — I didn't want to have people acting as us and all that sort of shit.

Which you could do. And I was getting people, literally even once I started writing the book, I was already getting offers to have movies made with actors. And I'm going 'no, this is too close to the bone' and I didn't want dramatisations of it. I wanted it be real.

And Mark was really sympathetic to that, and he made me really comfortable. He said 'we're only going to reveal and open up things, wounds, that you think you need to or you think you can learn from or you think that need to be told to tell the story'. So he was very close to me about it. And Andrew was actually, as a producer, was involved working with Mark all the time on that.

The first one, I was 'hmm, I don't know if I want to put this out', and then the book seemed to really connect with a lot of people. So that was really a good outcome for me and allowed me to let even more of that stuff go.

The second one, I just figured that because everybody had watched me growing up in public onstage, I thought because a lot of those people had read the first book, they would want to see how that affected me — and what effect that had for the good and the bad.

I wouldn't have been the wild rock 'n' roll singer I was had I not been brought up that way. Everything about being abused and unwanted and poor, and the violence and the alcohol in the house all the time, everything that happened to me made me the perfect melting pot to make me a rock 'n' roll singer.

Daniel Boud

I got there and all I wanted — even before I was in bands — all I wanted to do was for people to like me so I felt safe. And what better way for people to like you than to make the whole bloody country like you? I get up on stage and people go 'yeah, Jimmy, you're okay' — and I go 'yeah, I'm all right'. I'd be falling apart, but it would make me feel safe.

And as a traumatised child, to get people to like you they had to look at you. So I'm on stage going 'look at me. Look at me. Look, I can do this — like a monkey, I can do tricks'. And so I wanted people to see what I worked out was actually going on behind the pictures, behind the story that that we all knew that and that I'd created really as far as just being a rock 'n' roll singer.

And I wanted to prove that as bad as all that upbringing was, you've got to be thankful for who you are. If you can learn from it and grow from it, then you can learn to be thankful for all the gifts that were given to you in amongst all that shit — and it doesn't seem that bad anymore."

On Working Class Man Being a Family Affair, Like Everything in Barnes' Life

"They were always there — all the way through my life, my grown life, Jane was there. And she was just waiting for me and she was trying to keep me in the straight and narrow. And at times I drove her into the wild side with me, and there were times where it got out of control, but she was always just trying to keep things and be there for me as long as she could.

I think as much healing as I got from writing the first two books, I think the family got it, too. So as soon as I started to get myself together and started to deal with this, my family blossomed.

They've always been very supportive. Always there. The kids were always singing with me. I used to take the kids on tour with me all the time, and Jane on tour with me — we'd get teachers and tutors and nannies and stuff to bring them on the road, so we wouldn't be apart, because I was just afraid I was always going to lose them.

And as that changed and I started to become a better human being, started to understand my own life, I wanted them there for much better reasons: to share the joy of it with me. And so they went from going — they were always there, but the reasons for them being there and what they were getting from being there changed dramatically.

And so, in the end — because my kids naturally grew up and went into music, and Jane became a musician and a singer as well, but they learned that it was all about the joy, and not about the running and the hiding. And it wasn't just about the wildness and about bravado; it was about growing up and baring your soul to people, and making a connection with someone and walking away feeling like you belong.

And for me, for my children, for Ruby [Rodgers, who also appears in Future Council], my grandchildren, to feel that connection with an audience is, I think, it's probably one of the best gifts I could have given her in life — to feel that she can connect to people and connect with her own soul. When she started singing, she's done her first record, and it was nothing like any of us singing. It's just really sweet and beautiful. But we weren't all pushing her and telling her what to do. She just did it on her own. And she's found his voice, and she's found this direction that she wants to sing and the way she wants to communicate, which is really beautiful. But it was just because she was allowed, nurtured and it was encouraged that she find her own voice.

And I think that's one of the great gifts that we've been able to share in this family. And so they're all a part of this film, because they're all a part of my life and our lives are so entwined. Sometimes, for a while it was unhealthy, but now I think it's very healthy. I used to want Jane to be with me, of course because I love her, but also because I didn't ever want to lose her and I didn't want to be away and I didn't want to forget about her. Now it's just because I just adore her and we just want to be together all the time.

So the reasons sorted themselves out. And I realise that being together even through the adversity, there was times where it was probably more dangerous than doing good, but it also helped keep us together."

On How Barnes' Period of Reflection Has Inspired New Projects

"For a start, being healthier and straight and focused, I just have so much time. I'm hyperactive anyway, but obviously when I was medicating myself and drinking myself to a standstill all the time, it was hard to pick myself up to just even sing.

Nowadays, I'm so healthy. I was up at 7am this morning swimming laps. But I feel so healthy and so good. I just wake up and go 'right, what am I going to do now?'.

And I've got the cookbook coming out this October. I've written two kids books in the last few months for a couple of my grandkids, in at the publishers now. I've started writing more short stories. I've also started, last year or the year before, I started writing a novel, which I'm in the process of rewriting that.

I've got new songs that I've written for the next record. I have to slow down because you really can't put three records in a year. People will go really crazy.

But I'm just enjoying having the time and the energy to focus and do things that are creative and that are inspiring."

Daniel Boud

On Making Music That's Built Into Australia's Identity

"I think we're very lucky that we're a pretty real working-class band, really. It's a mixed bag actually, like Steve [Prestwich] and myself and Ian [Moss] — Ian comes from Alice Springs, he's a country boy; Phil [Small] was sort of middle working class; Steve and I were real working-class families. Don [Walker] was sort of the outsider. His family were writers and are writers, and were really beautiful writers. But Don wrote, he was a voyeur a bit, of life. And he looked at life and the lives that we had and wrote songs about them.

So I was lucky enough and we were lucky enough as a band that we wrote songs, that he was writing, that were influenced by us and influenced by what he's seeing around him. And those songs were so good they've connected with people. Our songs aren't about driving in your limousines or whatever. They were songs that were real earthy, and people connected to them. And I found songs like that, songs like 'Khe Sanh', songs like 'Flame Trees' — I could go on, there's a list of them all the way through. 'One Long Day'. Songs about people who just work in an office trying to get through the week, so they can have a nice time of the weekend with their girl or something. Those songs connected with people.

And over the years, the songs have become part of people's lives. We've been around for 50 years. We never changed. Cold Chisel was always a band, and same with me, people can walk up and say hello to you. We don't have security.

For a while I had security, because it was to keep me from people, because I was too wild. But Cold Chisel have always been approachable. They're always a meat-and-potatoes band. We're like the people we play for. And I think that made us connect with, that band, with those people.

And the songs are just — sometimes it really it brings tears to my eyes, because people come up and say 'I buried my father to your songs', 'I danced at my wedding to 'Flame Trees'', 'I danced at my bar mitzvah', whatever it was. All these different things and people, these songs were part of their lives, and that's something that we don't take for granted.

That's something that anytime we start to get a bit uppity, we remember this is why we play — to be connected to this society, to the people that we love so closely. And I think a lot of that has to do with the quality of songs."

On Barnes' Longevity, Including His Current Prolific Period

"I think it's a real blessing. I think one of the reasons why that happens is, as much as Cold Chisel went away for a while, we always all worked. We always stayed connected to our audience, to the music we love.

And one of the things I tell young musicians is just 'keep doing it because you love it. Some things are going to be successful, some things aren't. And if you just keep doing them, people connect, come and go'. And I feel, we've made maybe 50 records or something, or something more, and they've not all connected. But some of the ones that haven't connected are really special to me.

So if you make music for the right reasons, and you put your heart into it and you put your soul into it, and you're committed, people connect with you and I think you'll always have a career. And the thing is, I'll always have a career because I'll sing till the day I die. Whether I'm selling records or not is another story, but that's what brings me joy, is singing."

Jimmy Barnes: Working Class Man screens at the 2025 Melbourne International Film Festival.

MIFF 2025 runs from Thursday, August 7–Sunday, August 24 at a variety of venues around Melbourne; from Friday, August 15–Sunday, August 17 and Friday, August 22–Sunday, August 24 in regional Victoria; and online nationwide from Friday, August 15–Sunday, August 31. For further details, visit the MIFF website.