The Nose

Barrie Kosky's take on Shostakovich's work is opera, but not as you know it.

Overview

This is opera, but not as you know it. For a start, it's The Nose, the first opera written by Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich, who, at the time — 1928 — was just 20. Its basis is a surreal, satirical short story by fellow Russian Nikolai Gogol about Platon Kovalev, a civil servant who wakes up one morning in his St Petersburg home without his nose. He sets off to find it, only to discover it's become a character in its own right: a mischief-maker of superior social status. Along the way, Kovalev begs for help in a cathedral, police station and newspaper office, but encounters only callousness. Shostakovich fuels the protagonist's pursuit with a wild, chaotic score of changing time signatures, clashing harmonies and destabilising shifts in direction, influenced by folk, jazz and Gregorian chants. He co-wrote the libretto with Georgy Ionin, Alexander Preis and Yevgeny Zamyatin.

Secondly, it's in the hands of Aussie expat Barrie Kosky, current director of Komische Oper Berlin. Now, there are many ways to interpret the satire: is it a comment on society's obsession with appearances? A critique of classism and snobbery? Does Kovalev suffer a castration complex?

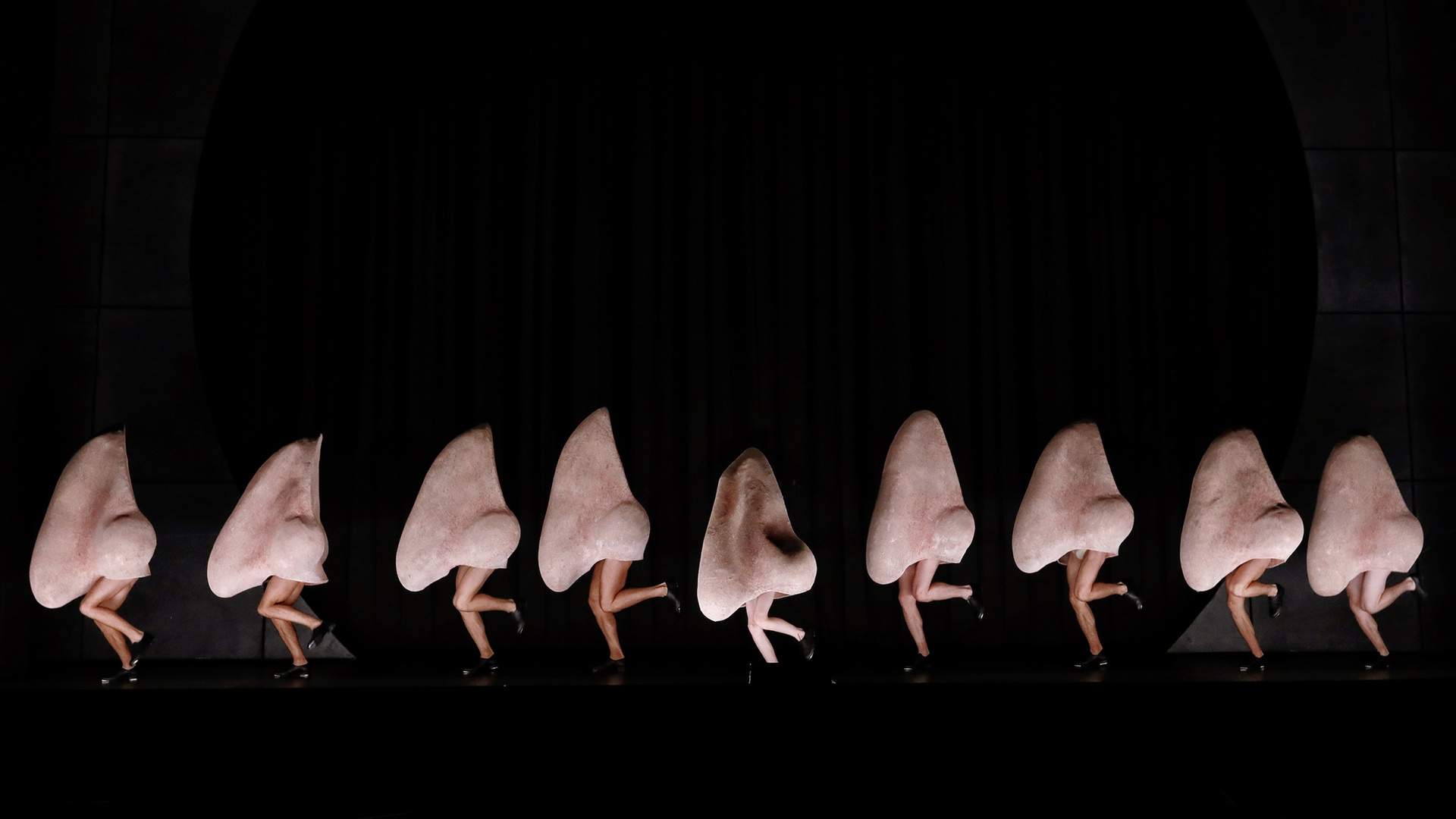

However, rather than choosing a single perspective, Kosky plunges Kovalev (Martin Winkler) into a dystopian world, in which the loss of his nose turns all order upside down. As he lurches from one institution to another, repeatedly met by indifference or outright scorn, his nose appears in various manifestations — here as a menacing shadow, there as a line of cheeky tap dancers. The singing, dancing, jeering crowd is a nightmarish maelstrom of corrupt police officers, worn-out journos and bearded cabaret dancers. Fart jokes, slapstick and disruptions of the fourth wall (at one point, an actor planted in the crowd calls out, "This isn't the Rooty Hill RSL, it's the Sydney Opera House!") interweave with rare moments of pathos, including a moving scene in which the clownish Kovalev sobs alone in bed, hidden beneath the sheets. It's fun and irreverent, but loud, brash, shocking, confronting and, at times, overwhelming.

The production, which features a new English translation of the libretto by David Pountney, is a collaboration between Sydney Opera House and the Royal Opera House, London.

Image: Prudence Upton.