Overview

In one of the many audio clips that comprise One to One: John & Yoko's impressive array of 70s-era archival materials, the documentary's two namesakes are asked how they want to be remembered. John Lennon's answer: "just as two lovers". It's an apt description, and one that applies in multiple senses in the latest film by Kevin Macdonald — a doco that joins the likes of Oscar-winner One Day in September, plus Touching the Void, the crowdsourced Life in a Day, and the also music-focused Marley and Whitney on the Scottish director's resume, as well as features such as The Last King of Scotland, State of Play, How I Live Now and The Mauritanian. Standing out in the the well-populated realm of Beatles movies, factual and dramatised alike, One to One: John & Yoko steps through Lennon and Yoko Ono's love for each other and for music, and also for doing what they can to make the world a better place.

As much as that "two lovers" quote resonates in the movie, that idea wasn't one of the lenses through which Macdonald, a lifelong Beatles fan and someone who considers Lennon his first pop-culture hero, approached the film. "Not specifically, actually, the kind of love affair between them," he tells Concrete Playground. "I think that comes across as between the cracks, in a way." Instead, in a film that explores a marriage, a milestone concert that also gives the doco its title, and a moment — that's as fascinated with the reality that greeted John and Yoko when they moved to the US from Britain in 1971, how the couple witnessed the era through American TV and their activist efforts to make a difference IRL — he was keen to show Lennon and Ono's romance as a union of equals.

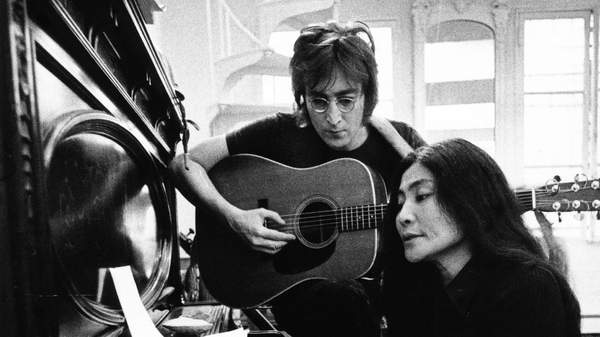

© Bob Gruen / www.bobgruen.com

"I was very interested, though, in trying to give Yoko a bit more of a voice and get her perspective on this period, and on the immediate aftermath of this breaking up of The Beatles and the influence she had on John. And for the audience to see, I think, what to me was very clear as I looked at all this material — is that this is a real marriage of true partners, love partners but also creative partners, and the respect that they have for each other comes across in the film," Macdonald continues. "I think it's a very mature kind of love, I suppose, as in it's not the kind of usual movie romantic, tweeting-birds kind of love. It feels like love that is part of a profound relationship of respect. I think that's what's so striking about it."

"And I'm particularly struck always by, when I watch the film, by seeing John go to the International Feminist Conference at the end — and thinking in early 1973, which other massive rockstar of that period would do that, would be the only man in the room with a bunch of very hardcore feminists, and be open to that, those ideas and that experience, and giving the platform to their partner in such a way? I think that even today, that would be quite rare with a male star."

Macdonald's latest documentary started its life with the One to One concert footage, which was John's last full-length gig — and also his only one after The Beatles. An interview that the filmmaker heard with John speaking about how all he did was watch TV when he arrived in the US, which is quoted at the beginning of the movie, was just as crucial. So began a project with a tricky task, given how frequently cinema's focus falls upon John and The Beatles still. The job: when Sam Mendes' (Empire of Light) four films starring Harris Dickinson (Babygirl), Paul Mescal (Gladiator II), Barry Keoghan (Bird) and Joseph Quinn (Warfare) are on the way — and the Martin Scorsese (Killers of the Flower Moon)-produced Beatles '64 arrived in 2024, The Beatles: Eight Days a Week from Ron Howard (Jim Henson Idea Man) came out in the last ten years and The Beatles: Get Back by Peter Jackson (The Shall Not Grow Old) isn't even half-a-decade old (and that's without thinking about Nowhere Boy and Backbeat and so much more) — how do you come up with something that feels new?

The answer here: fleshing out One to One: John & Yoko not only around the Madison Square Garden benefit concert for children with intellectual disabilities at Staten Island's Willowbrook institution, and not even just through the pair's music, either, but also by using their television viewing to give context to what was happening in America at the time. Also, by giving the movie the vibe — with home movies, plus unheard tapes of John and Yoko's phone calls, too — of hanging out with the pair. Accordingly, Macdonald pairs restored 16mm footage of the pivotal gig with personal clips, archival news, TV snippets and commercials, and even a recreation of John and Yoko's Greenwich Village apartment from the era. The duo's presence in the political and social movements of the time is in focus as well, as is simply revelling in their presence together.

Sean Ono Lennon has said that it's the first film that's truly captured who his mother was as an artist and a person, Macdonald has shared. That's one of many striking elements to the doco. How clearly it highlights the similarities between the 70s and now, how it embraces John and Yoko's fondness for creative experimentation in its approach, its collage-like structure that the director likens to TikTok: they're others. We chatted to Macdonald about the above, plus what it means to him to make One to One: John & Yoko as such a Beatles and Lennon fan, his career journey and more.

On Sean Ono Lennon Saying That This Is the First Film He's Seen That Has Truly Captured His Mother as an Artist and a Person

"I was really happy with that, obviously, because first of all, you make anything about The Beatles or about The Beatles solo and there's so many films and so many books, and so much has been said and written. So to try to do anything that's new, that was my starting point.

I don't want to make a film like every other film that's been made. I want to show something different. But I'm not going to factually show you much that's new — there are probably some things up here that the real Beatles fans can go 'oh that, I didn't know this little fact, that little fact', but it's not really about that.

To me, it's more about the experiential thing of being with these people in a very domestic, everyday setting for a lot of it. I mean, just hanging with them. And I wanted people to have the sense of hanging out on the bed with John and Yoko. So naturally, of course, that means that you, because you're seeing Yoko not always in her public persona, I think you feel closer to her.

And I think there's something about the phone calls, the phone calls that she's on — particularly the one where she talks about how The Beatles treated her, and how people sent her dolls with pins in them and things, which I think give you a great deal of empathy for her, which then is redoubled when you hear the story of her daughter Kyoko. Which, by the way, I thought I knew quite a lot about The Beatles — I didn't even know about Kyoko.

And I think that says an awful lot about how her perspective has not been taken in terms of telling the story in the past. Because John and Yoko went to New York largely because they were looking for Kyoko. They were escaping from what they perceived as the unwelcoming attitude in Britain for Yoko, but they were primarily there because they were trying to find Yoko's daughter. And that drove them through all of this period, and yet that's not something that's talked about.

So I as soon as I started to learn about that story and learn about how that was really the emotional driver for the concert being put on in the first place — this sense that both of them had for the terrible conditions that these kids were being brought up in, which was particularly raw for them because they both undergoing this sense of loss of Kyoko — I think once I put all that together, that gave a perspective on Yoko emotionally, which I think changes the way you feel about her. Because when you empathise with someone, you tend to like them more."

On the Importance of Giving One to One: John & Yoko a Tangible Element Through a Detailed Recreation of Lennon and Ono's Greenwich Village Apartment

"When I got involved in the film, as I said, I was thinking first and foremost about 'how can I open up a different kind of window on them and give people a sense of getting to know them on a deeper, more immediate level?'. And I heard this comment that John made, very early on in my research, where he talked about how television was his window on the world, and how he spent most of his time when he first arrived in America watching TV and learning about the country through the TV. And I thought — that's a light-bulb moment, I thought 'well, that's how I should structure the whole film, is around that concept. And we should see them watching TV or feel like we're with them, feel like they just left the room and they left the TV on and the cigarettes still in the ashtray'.

And so, as I said earlier, to have the feeling that we are on the bed with them, watching what's going on in America — and I like the idea that we're understanding history through shards, in the same ways we do in everyday life. We don't have a perfect knowledge or understanding of what's going on around us. We pick up little bits and pieces, and we create a narrative in our heads. And that's I wanted to reproduce, that experience, which is the experience of how human beings pass through the world.

We don't have perfect narratives that are presented to us and everything coheres and makes sense. We are taking these imperfect little moments and giving them meaning and putting them together in narratives."

On Whether Macdonald Anticipated the Parallels Between America in the 70s and Today That Are Evident inthe Documentary

"No, I actually didn't. I didn't. We started this, I guess, in early 2023, and the legal situation, the political situation in the world, was very different. And it did feel at times — still does feel — like the world is copying our movie. Things keep happening that we're like 'oh my god, that's like the scene where such and such happens in the film'.

And I did for a long time wonder about whether, is this kind of echoing, is this something? I've since read quite a lot about it, actually, and I'm not the only person to have noticed it — it is something which quite a lot of historians have commented upon. And I think even if you go back in time, there's even earlier periods in American history which have a similar rise of populism, demonstrations, economic turmoil.

I think a lot of those things come back in some cyclical way in America every 50–60 years. And I think that they'll probably come back in different ways in other countries. I think it's something I'd be very curious to find out more about.

But I was struck, as we were making the film, that all these echoes and similarities just arose around me. Because it really was — we didn't know that Donald Trump was going to have an attempted assassination. We didn't know that Kamala Harris was going to be the first Black woman to stand for presidency. And we had Shirley Chisholm, who was trying to get on to that ticket [in 1972]. All these many, many connections, they weren't there when we started cutting the film, even. So it was peculiar.

But I think that why I find it comforting in a way, is that we all like to think that our period is a particularly catastrophic, apocalyptic period. It's a kind of vanity, I suppose, we all have as human beings — you think 'oh my god, we're living through the worst of times'. But actually, to see that things were pretty bad before, passions were very high, and then we had Jimmy Carter and things. We had sort of boring presidents and stabilisation in the world, and things did get a little better.

I suppose I took some comfort from that. But I guess you can read it also the other way around. You can read it as 'oh my god, why don't we learn anything?'."

On Making One to One as a Lifelong Beatles Fan and Someone Who Considered Lennon His First Pop-Culture Hero

"I think I — maybe in common with other people, I don't know — the passions that you have when you are in your early teenage years, or between the ages of 11 and 16 or whatever, you never feel passion for anything quite as much again in the way that you did for those things. Whether they be movies or songs or artists, whatever it is, I think you're more open and raw, and everything is new to you and it's super exciting.

And so to be able to go back to one of the people who really was my great hero of that [age]. I think I was aware of The Beatles in 1979 when I was 11 or 12, and then John was shot, and then that confluence of those two things is what made him such a focus of attention for me. But I think that to be able to revisit that period of your life is real pleasure — from an adult perspective, from a more cynical, seen it all, been-there-done-that perspective. Because it reminds you of who you are and the passion that you had. And you can see how right you were in some ways, to love those things. And it reawakens that love that maybe you were a bit cynical about it.

So yeah, I think I find myself, interestingly, in a lot of films and documentaries I've done, going back to this period in the 70s — which is, I guess, the formative period for me. I had an American grandmother and I used to go to stay with her all my holidays in America and watch TV. I remember the Nixon hearings and things like that being on TV. And I remember my grandmother supporting Nixon. I remember her vividly saying 'oh, that poor man, Mr Nixon, why don't they leave him alone?'.

So maybe we're all revisiting our childhood experiences."

On Whether One to One Was Actively Aiming to Match Lennon and Ono's Creative Experimentation with Its Own Approach

"No, not so much. I was looking at what remains of them and what it says. I thought it would be an interesting process to just say 'I'm not going to take any extraneous information, very little extraneous information, in the film, except that which exists in archive footage and audio and whatever. I'm going to see what I can make, how I can create an experience, but also somewhat of a story'. And it's always a balance in this sort of film.

I wanted it to be something that when you experience narrative, you feel like things move forward and change, but for it to also feel moment to moment like it's chaos and anarchy, and you don't know where it's going to go. But actually, I want the audience to feel that, as they watch it, like 'oh, the filmmakers do have an idea — they are taking me somewhere. This is going somewhere. There is a progression. There is a narrative'.

So it's trying to finely balance the chaotic and the structured. And there is a very thought-out structure to it. But it just seems to me like it's interesting to use the crumbs that have been left down the back of the sofa. You can put it like that. It's like you live your life and most of it vanishes with you when you're gone, and those times are gone, but certain crumbs are left down the back of the sofa, and a few coins that fell out of your pocket — and what do they say about you?

And they're not the whole truth. They can't be. Because we can never reconstruct the whole truth of the past. And then, not to get too pretentious, so that's what different documentary forms which are about the past are trying — different ways to evoke and describe that which you know can't be fully brought back to life, can't fully be understood, in an hour and a half or two hours or whatever it is.

And so there's a joy for me in the experimentation, and in the trying to find a different way to bring this period to life, to bring these characters to life, to mix their personal lives with the bigger political scene, and the bigger cultural scene, without trying to explain it all too much.

I've had younger viewers watch the film and say 'this is like the TikTok experience'. This is basically how young people experience the world, watching TikTok, where you just see people, characters, situations appear, and you are very rapidly are making calculations in your head about 'who are they? Where they from? What's the purpose of this? Are they selling me something? Are they just trying to be funny?'. And I think that's the way I want be able to experience this film — that you're making all these connections. You're not being totally passive in it. You have to bring your own mind, bring your own sense of narrative to it."

On Macdonald's Three-Decade Career So Far, Including Jumping Between Documentaries and Dramas

"I feel, on one level, just really lucky to continue to be able to make films and continue to be able to make them in the way that I want to make them. And I have to give thanks to Mercury Studios, who let me make this film — sort of a mainstream experimental film, if we call it that.

And to get the opportunity for people to give you money to be able to make a film is always a privilege. To get a make a film which is idiosyncratic and personal is really an exceptional thing.

So after 30 years of making documentaries and films, yeah, first of all I just feel lucky to have been able to do that and to have supported myself and made a living out of doing it. And I love doing something which you can never perfect. You're always having to realise what did and didn't work in what you last did, and try to do something new — and I think that's maybe the defining feature of my work, which is that it's very varied and I'm always excited to try something different, try something new and go with my own passions for the most part. Although sometimes, obviously, we do things for money — but for the most part we do things for passion.

And also, I'm very happy that I've continued to do both documentary and fiction — and the breathing space that each one gives me and renews in me, that gives me the time to renew my passion for the other one. So when I make a documentary, I'm at the end of it and I'm like 'oh my god, I really want to work with some actors who give me exactly what I asked them to so I don't have to find it in all this footage' and vice versa."

One to One: John & Yoko opened in Australian cinemas on Friday, June 20, 2025 — and streams via DocPlay from Monday, July 21, 2025.

Images: Magnolia Pictures.