Overview

Portraits aren't all regal furs and awkward "Oh, didn't see you there," poses. Tim Storrier nabbed the Archibald Packing Room Prize today with his unflattering-as-blazes portrait of Dr Sir Leslie Colin Patterson KCB AO, with this morning's announcement of the finalists for Australia's prestigious Archibald Prize. Capturing a realistic, unrelentingly vulnerable likeness of your own reflection, someone you've just met or one of your oldest buds takes a fair few stories, maybe a few beers and a willingness to tackle the intimidating notion of thinking up something new after decades of Archie winners.

At the risk of sounding like an HSC essay opener, the final image isn't the whole story. Here's eight of the Archibald finalists making us wake up and pay attention (whether for great or WTF reasons) to Australia's big ol' faces — as told to the Art Gallery of New South Wales in their own words.

Peter Churcher, Four self-portraits in a bunch of balloons

"One particular evening I was walking down a street and coming towards me was a fellow holding an enormous bunch of balloons. I thought it would make a wonderful subject for a still life. I set up a large bunch in my studio. To my delight, I noticed my own reflection very clearly looking back at me in many of the balloons. I particularly like the way each individual balloon slightly distorted my reflection the way those mirrors in the funfair used to.

"I quickly realised I was no longer looking at a straightforward still life. The subject had transformed into a quadruple self-portrait showing myself in my painting studio in four different ways. All this sets up a complex set of different scenarios within the painting. Who is looking at what? Who is looking at who? Is it a still life or a self-portrait?"

James Powditch, Citizen Kave

"I want to stop people in their tracks with this work and have them scratching their heads, thinking “that’s one hell of a film, how come I don’t remember it? Then when the penny drops that it’s all make believe, that it’s a 'what if' picture from 30 years ago, they’ll start thinking about what they were doing back then, remember all the influences and events in their own lives, all the stuff that moulds us over time and makes us who we are.

"Artists like Nick Cave gather all that stuff up: a book from here, a great film from there, music and art. It’s all repackaged and sent out into the world where it is evaluated, absorbed and informs the next generation. He becomes an influence — or if they saw him, maybe a pivotal moment in their lives — and the process just keeps rolling along, repeating endlessly. So the painting represents an imaginary rock opera made in 1983 when Cave was 26 years old, the same age as Orson Welles when he made Citizen Kane in 1941. But it’s about a modern-day media tycoon, Rupert Murdoch rather than William Randolph Hearst. I see Cave and Welles as similar, extraordinary talents, across multiple disciplines."

Sophia Hewson, Artist kisses subject

"I sought out working with Missy [Higgins] because I belt out her songs in the car. I also know her to be genuinely egoless with a deep respect for artistic autonomy, which meant she was willing to work with me outside the traditional portrait structure.

"I’ve been thinking about the proximity of the orgasm to death and spiritual revelation. In my work I’ve been considering the orgasm as a kind of transcendence, and using metaphors like 'orgasming against something plastic' to explore the human experience of when revelation falls short and faith is not found. In this painting it is the constructed nature of the intimacy that suggests ecstasy is just out of reach. I wanted to create something equally portrait, self-portrait, and an examination of post-feminist self-objectification."

Rebecca Hastings, The onesie

"It’s difficult to take anyone seriously when they are wearing a onesie. In this self-portrait I mock my own inadequacies as a mother and lament the struggle to also be an artist. Instead of a paintbrush I hold aloft a lollypop-like object, satin gloves replace my usual hand protection, and the painter’s apron becomes instead a shimmering onesie.

"As a mother of two children I find myself constantly beset by guilt, frustration and anxiety. I consider myself ill-equipped and a bit of a joke when it comes to meeting the lofty, idealistic heights of mummy perfection. This painting is part of a broader exploration of themes relating to 'maternal ambivalence', reflecting my desire to subvert the romantic ideal of motherhood, and chart the unacknowledged, darker side of the complex and contradictory experiences that come with having children."

Wendy Sharpe, Mr Ash Flanders, actor

"I first saw Ash in a production called Little Mercy. He played Virginia, the mother of an evil seven-year-old girl. Although it was crazy and surreal, Ash played her absolutely straight. It is really moving when something can be ridiculous, funny and poignant at the same time. Ash has now been cast as Hedda Gabler, the female lead in Henrik Ibsen’s famous play at Belvoir Street Theatre: a brave and exciting choice. He is not being a drag queen but will play Hedda seriously with intelligence and sensitivity.

"This painting is not about Ash himself but about the uneasy stage persona he will create as Hedda Gabler. The disturbing mix of masculinity and femininity was what excited me to paint the picture. Ash understood exactly what I was after. We worked together in my studio trying different poses and clothes (my dresses, his shoes) to get something intriguing and unnerving, vulnerable and powerful. I was thinking of the paintings of Edvard Munch who, like Ibsen, was Norwegian."

Sally Ross, Harvey

"His [Harvey Miller of Flight Facilities] elaborate corporate narratives and performances combine beauty, brains and youthful hedonism with rump-shaking, turn-of-the-nineties synth pop, blurring the line between art and pop, performance and cultural satire,’ says Sally Ross. ‘When I first saw his epic Aussie montage music video End of the Earth, I thought I had just experienced the work of Barry Humphries’ secret love children. Harvey and lead singer Monte Morgan have featured in my paintings ever since.

"I want to paint clever people that I get to meet in my life, creative people that dare to make the leap of faith required to make art, perform, put their ideas out there. This is a labour of admiration and enthusiasm. My portraits are about asking what do clever people look like? Can a picture have a presence? There is a particular, quite intimate scrutiny created when you paint someone. When I do the “reveal” and show the sitter their portrait for the first time it is completely awkward and wonderful."

Rodney Pople, Well dressed for a Sydney audience

"During his Weimar cabaret in Sydney last year, Barry Humphries commended the crowd as being “well dressed for a Sydney audience”. The same could have been said of the performer. Later, as he transitioned from performance mode to talking with me backstage, I glimpsed a momentary uncertainty behind the facade of Humphries’ various theatrical personae. It is this image, in addition to the sketches made both backstage and from my seat in the audience that evening, on which the painting is based. The result has, to quote Humphries’ response upon seeing the finished painting, achieved a 'more than flattering likeness'.

"The portrait takes its composition form Max Beckmann’s Self portrait in tuxedo 1927, chosen because of Humphries’ interest in Weimar culture. The work of both men combines unsentimental insight and sharp satire to comment on the contemporary society of their respective eras. Where the Beckmann self-portrait conveys a sense of assurance, this painting reveals insight into the man as he moves between roles from stage to sitter. Beckmann’s portrait describes a man at the height of his powers; similarly, this portrait of Humphries celebrates the outstanding career of a man at the pinnacle of success in his 80th year."

Paul Ryan, Rox

"It was Rox’s inspired character Cleaver Greene in the television series Rake that was the catalyst for my desire to paint [Richard Roxburgh]. My regular practice is an exploration of ideas and images of early colonial men and wild colonial boys: lieutenants, squatters, cowboys and dandies. Cleaver Greene is a contemporary portrait of the wild colonial boy. A larrikin, drunk, womaniser and dandy, he falls somewhere between hero and anti-hero. Some of us want to be him, until he wakes with a hangover in another man’s bedroom with another man’s wife.

"The painting is a portrait of an idea of Rox. He is dressed in colonial coat and shirt. It has elements of a likeness but is clearly not a photographic likeness. In the early stages it looked more like Rox but I wasn’t happy with the paint. I moved it around in vigorous swirls with large palette knives. In an instant the image changed and came to life. I had broken free from the constricting desire to capture the face. For me, the best portraits move on from likeness and go deeper."

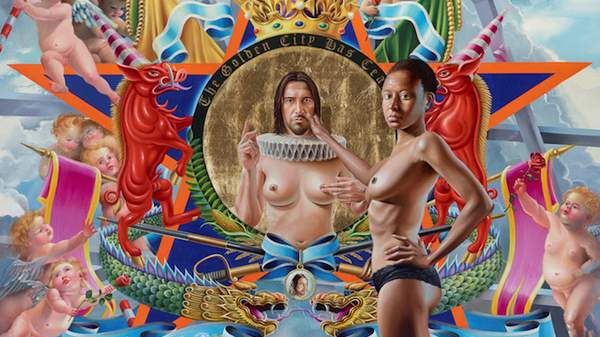

Peter Daverington, The Golden City has ceased

"This is a self-portrait of my imagination, where my signature geometric and spatial elements appear among figurative compositions drawn from various painting traditions. The painting’s title is inscribed as a motto beneath the coronet within a coat of arms. The phrase comes from the Old Testament book of Isaiah and refers to the fall of Babylon. In the centre field is a self-portrait in which my face and arms are connected to a female torso. I appear again in a portrait miniature hanging from ribbons beneath the ring. A second motto written at the base of the star on a blue scroll reads From the future with love. My wife Kianga stands on the step-ladder. The image of burning buildings at her feet is taken from a photograph of the fall of Baghdad in 2003.

"This painting developed intuitively over 18 months. I have drawn inspiration from socialist propaganda posters, Renaissance art, Romantic landscape painting, medieval European heraldry and religious iconography. The unusual combination of breasts and beard has an interesting precedent in Jusepe de Ribera’s The bearded woman, a portrait of a husband and wife from 1631."

Find more stories and the rest of this year's Archibald finalists at the AGNSW website.