Concrete Playground’s Summer Reading Guide 2013

Read books this summer. Read these books.

Summer is upon us! You could have looked at a calendar for that information, but the fact has only dawned on me this week. Primarily due to the preponderance of sunshine threatening to burn my pale skin, and the fruiting mango tree outside my window in which Sydney’s entire bat population have been spending evenings hosting barn dances or their national AGM, or something that at the very least involves a lot of screeching designed to keep me sleepless and cranky. And, as always, you know it’s summer because you’re finally looking down the barrel of a few months in which you can relax, wear skimpy clothing, drink your liver into retirement and spend long hours sitting on beaches or in backyards with a book.

In an effort to keep my recommendations timely, all the books included in this summer reading guide were published in the last year. Well, year-ish. Some of them came out in 2012, but I was a bit slow on the uptake. And they are really very good, as is everything included on this list, regardless of my arbitrarily self-imposed rule. As ever, I would gently recommend searching out a copy of whatever takes your fancy at your local, independent bookshop. They are more in need of your dollars than Book Depository.

The Flamethrowers by Rachel Kushner

The Flamethrowers is one of the most beloved books of the year, for good reason. Suffice to say, it is very much worth your time. The novel is centred around Reno, a young woman just arrived in New York from art school. It’s 1977, and she’s intent on turning her fascination with motorcycles and speed into art. This coincides with her affair with Sandro Valera, an older man descended from Italy’s foremost motorcycle manufacturer, a man at the centre of the explosion of activity in New York’s art scene. The book shifts from the dreamers, performers and ciphers of the art world to Reno’s childhood in Nevada to the family history of Sandro’s family in Italy and finally to the political radicalism on the streets of Rome, in which Reno is cast adrift. The Flamethrowers is a complex, disorienting, beautiful book, but most importantly it’s alive. Every page is electric.

The Best of the Lifted Brow V1

The Lifted Brow is Australia’s most interesting and innovative magazine.* It’s sincere and it’s funny and it’s excessive and it’s dangerous. It’s proof — if proof was needed — that the publishing industry in this country isn’t chasing it’s own tail around a gurgling drain. There is incredibly exciting, brilliant work being produced, and much of it is being published by The Lifted Brow. This volume comprises some of the best writing TLB has published since it was founded in 2007. Inside, you’ll read nonfiction from Benjamin Law, Sam Cooney and Alice Pung. Michaela McGuire works in a casino, Luke Ryan gets cancer, Liam Pieper investigates the history of cocaine in Australia, and Romy Ash hunts and cooks a rabbit. There’s original fiction from Tao Lin and David Foster Wallace and Frank Moorhouse; stories about bone-struck hearts, holy water, a shipwrecked man and a chimpanzee; and a list of the pornography available for download from the United Dairy Council. So the next time somebody tells you the print industry is dead and nobody has anything original to say anymore, gently thrust a copy of this book into their hands.

*Full disclosure, The Lifted Brow has been kind enough to publish some of my own scribbling.

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz

Junot Diaz’s writing is explosive. The Dominican-born American author writes in a dialect often described as Spanglish, but that doesn’t even begin to acknowledge all the other idioms he taps into when he tells a story. There’s Spanish and there’s English, sure, but there’s also the language of sci-fi, nerd-dom, hip hop, drugs and the literary canon. And there’s quite a bit of swearing. A typical sentence of his reads like this: “Dude was figureando hard. Had always been a papi chulo, so of course he dove right back into the grip of his old sucias, snuck them down into the basement whether my mother was home or not.” That comes from the story The Pura Principle, published in Diaz’s third book, This Is How You Lose Her. The book is a collection of interwoven stories narrated by Diaz’s alter-ego Yunior, who also appeared in Diaz’s first collection, Drown, and the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. If you’ve read either of those books you’ll know how brilliantly Diaz sweeps you up into the world of his writing. This Is How You Lose Her does the same thing, only better.

Taipei by Tao Lin

Tao Lin is widely considered to be a kind of hipster-savant. A novelist, poet, publisher and artist, he’s one of the first writers to have been formed by social media and the internet instead of traditional print culture. His writing is light on plot, mirroring the kind of prose generated by Twitter, Gmail and Tumblr. His writing acknowledges that the record of an individual’s impulses and desires alone can be a worthwhile subject for literature. And while that has struck some critics as needless, navel-gazing overspill, Taipei is the best thing Lin has written so far, and one of the most interesting books published this year. It’s an account of a year or so in the life of Paul, who is pretty clearly a stand-in for Lin himself. Paul wanders around New York and Taipei, doing a lot of drugs with his girlfriend, and spending a lot of time alone, craving solitude and darkness despite the depression and affect-less self obsession which lurk in his psyche at all times. Above all, the book is about the desperate, howling desire to connect which characterises the present.

Tenth of December by George Saunders

In a year when the short story has been re-energised and shoved into the limelight by the awarding of the Nobel Prize in Literature to Alice Munro, George Saunders has been widely lauded as the future of short story writing. Tenth of December is Saunders’ fourth, and best, collection of stories, published to huge acclaim at the beginning of the year. There are stories about rape, abduction, suicide, the frustrated rage of tightly wound people, the post-traumatic impulse of a former soldier to burn down his mother’s house. But these stories aren’t grim. They’re inventive, the language twists and turns, they’re buffeted by anarchic good cheer and merriment. It’s only when you put the book down that you realise how dark the stories are, and the sheer talent of the man who’s crafted them. If you want a taste of the collection, the final story in the collection is free to read here.

Night Games by Anna Krien

Anna Krien’s book is ostensibly a work of investigative non-fiction beginning on the night of the 2010 AFL grand final, and the rumours of a gang rape that began to circulate the next morning. Two Collingwood players were linked to the rape, but in the end one young man, also a footballer although not with the AFL, was charged. The book follows the case from beginning to end, but in the meantime it branches out into many different issues. It’s a story about top-level football, the problem of prosecuting sexual assault, and the treatment of women. But it also highlights the grey areas, the uncertainty, in the way human beings interact with each other. It’s a beautifully written book about deeply complex issues, and it’s that which makes it one of the best pieces of investigative non-fiction I’ve ever read.

All That Is by James Salter

One of the best things I did this year was start reading James Salter’s novels. Despite being one of the best writers of the 20th century, he has never gotten the same kind of recognition, or sales, as many of his peers. He’s frequently called a ‘writer’s writer’, which basically means that people who do their own scribbling think he’s the bees knees . But he is truly one of the most beautiful writers you could possibly read, and All That Is is a very good place to start. All That Is is Salter’s first novel in over 30 years. On the surface of it, the story is fairly simple: it follows Philip Bowman over a period of 40 years, from his youth at the end of WWII and as an editor in New York, through marriage, divorce and a series of middle-aged affairs. What sets it apart is the intensity of Salter’s language, the burn and clarity of the fast-flowing scenes.

How Should A Person Be? by Sheila Heti

How Should A Person Be? is a strange, wonderful novel, arguably one of the most influential books published in the last five years. Subtitled, 'A Novel from Life', it’s a book which sits within a contemporary literary movement bored and frustrated by conventional fiction writing. The book is thus a number of things at once — a confessional, a manifesto, a novel, and a self-help manual, revolving around the life of ‘Sheila’ and her friends in Toronto’s creative community, delving into questions about art, sex and female friendships. Heti claims to have been inspired by reality TV, particularly The Hills, and so many of the emails and transcribed recordings of conversations come from real life. But the book is also shaped, forced into a plot, and sits somewhere at the blurry edges of fiction and memoir. It’s a beautiful and engaging book, and it likely to be a huge influence on contemporary writing for years to come.

Ninety9 by Vanessa Berry

Ninety9 is a memoir of what it was like growing up in suburban Sydney in the ‘90s, written and illustrated by Australia’s foremost zine-maker. Vanessa Berry came of age when triple j was just going national, when the street press was still the arbiter of all things ‘indie’. She grew up pressing ‘record’ on cassette tape decks; compiling handmade zines and sending them through snail mail; staying up late watching Rage; covering her bedroom walls in Teenage Fanclub, The Cure and My Bloody Valentine posters; and creating an identity for herself as a Goth in a city which mocks your melancholy by bathing you in relentless sunshine. It’s a beautiful memoir about adolescence and the lost landscapes of Sydney’s independent fringes, before the Millennium rolled over and the line between alternative and mainstream became dizzyingly vague. For those who like doing two things at once, Vanessa Berry has also compiled a special Ninety9 mixtape to accompany the book, which you can listen to right here.

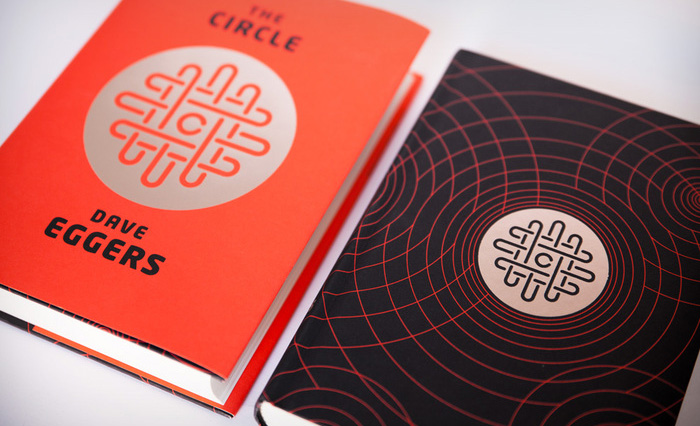

The Circle by Dave Eggers

Dave Eggers, founder of McSweeneys, is without doubt one of the best writers working today — have you read A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius? You really should. Be that as it may, The Circle, Eggers’ newest book, is an excellent example of his tendency to take important contemporary social issues and turn them into interesting, innovative literature. The book, in the tradition of Orwell’s 1984, is set a couple of years in the future, and follows Mae Holland as she begins working at The Circle, the world’s most powerful internet company, which has eclipsed and merged with Google, Facebook, Twitter, etc. The book raises questions about the power of technology to regulate and orchestrate human behaviour, and the way that the dictums of ‘sharing’ and ‘openness’ are beginning to take on a dangerously cult-like loyalty. It is a deeply disturbing book, but it’s also effortless to read, making it the closest thing to a ‘page-turner’ on this list.