-

News

From Barley to the Bottle in the Heart of the City

Watch your beer 'grow' from start to finish at this temporary inner city brewery.

-

News

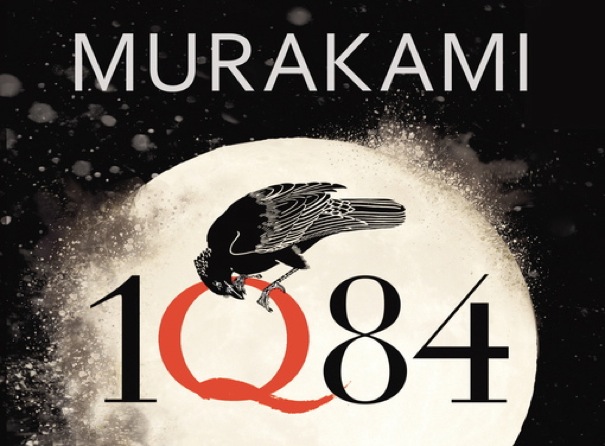

A Guide to this Summer’s Best Beach Reads

In attempt to help out those with a literary whim, Concrete Playground presents the ten best books to read this summer.

-

News

Engagement Photos, Star Wars Style

An American couple have taken their love for Star Wars to a different level by dressing up as the movie's characters for their engagement shoot.

-

News

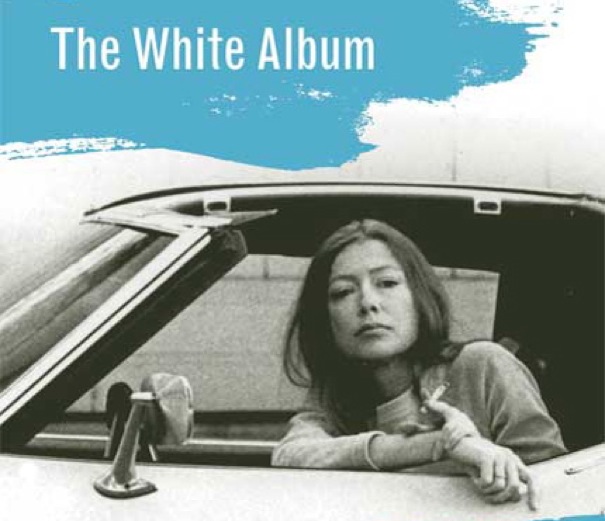

Concrete Playground’s Summer Road Trip Essentials

Road trips can be an idealised summertime activity, so Concrete Playground has come up with some tips to make sure you never have a bad one again.

-

News

The Spirit of Youth Awards Set to Grow in 2011/2012

With the competition's expansion into unprecedented categories, there are now more opportunities for Australia's finest creative minds to showcase their work to the world.

-

News

Benetton Receives Hate for its ‘Unhate’ Campaign

The United Colors of Benetton are the centre of controversy after their new 'Unhate' campaign showed some of the world's leading figures locking lips.

-

News

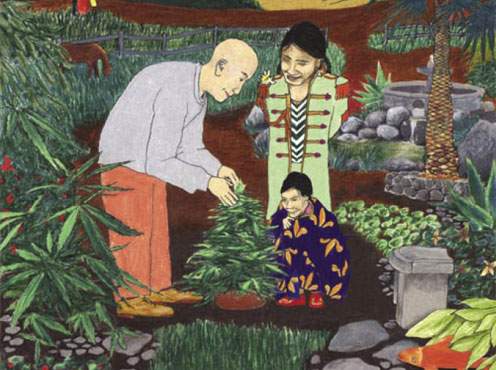

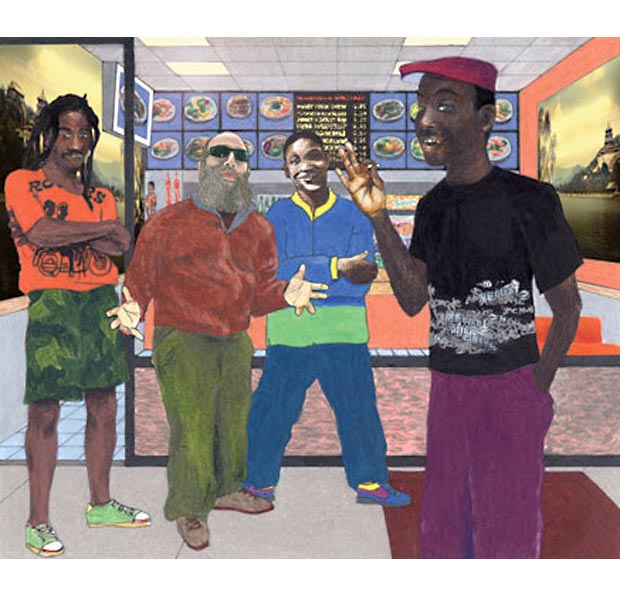

It’s Just a Plant: The Children’s Book on Marijuana

The story of a young girl's educational journey as she comes to understand cannabis, explained to her by her parents, a doctor and a kind gang of Rastafarians.

-

News

The New Seven Natural Wonders of the World

With so many fantastic places to visit around the world, it's often hard to decide where to possibly go. The New7Wonders makes it a little easier for you.

-

News

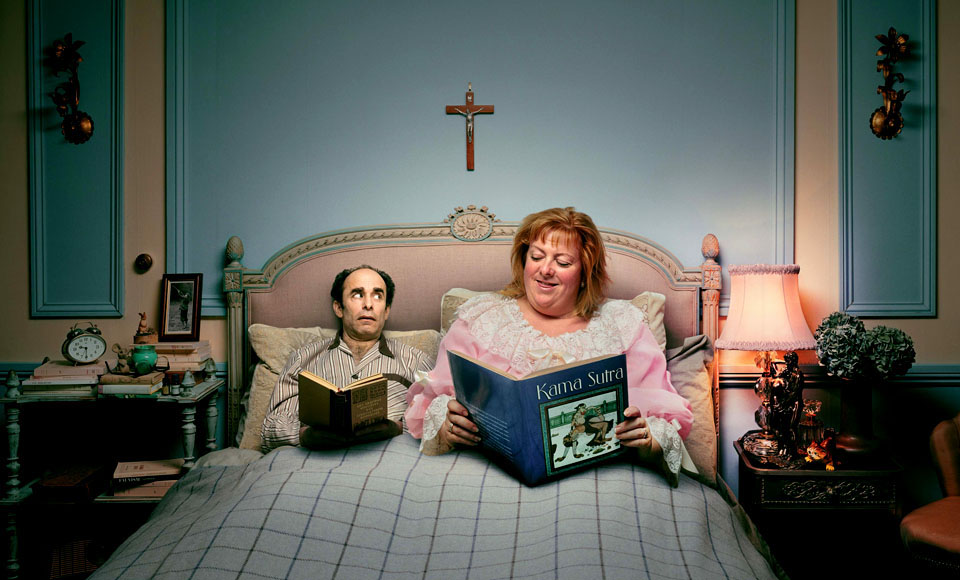

Concrete Playground talks to Photographer David Stewart

Concrete Playground recently caught up with one of England's most respected photographers. Here's what he had to say.

-

News

Win a Priceless Night Out with Florence + the Machine

Win the ultimate night out on the town for you and three friends.

-

News

The Ten Best Bars in the World

Your local favourite may not be on the list, but rest assured that all fifty are well worth the visit next time you find yourself in one of the world's culture capitals.

-

News

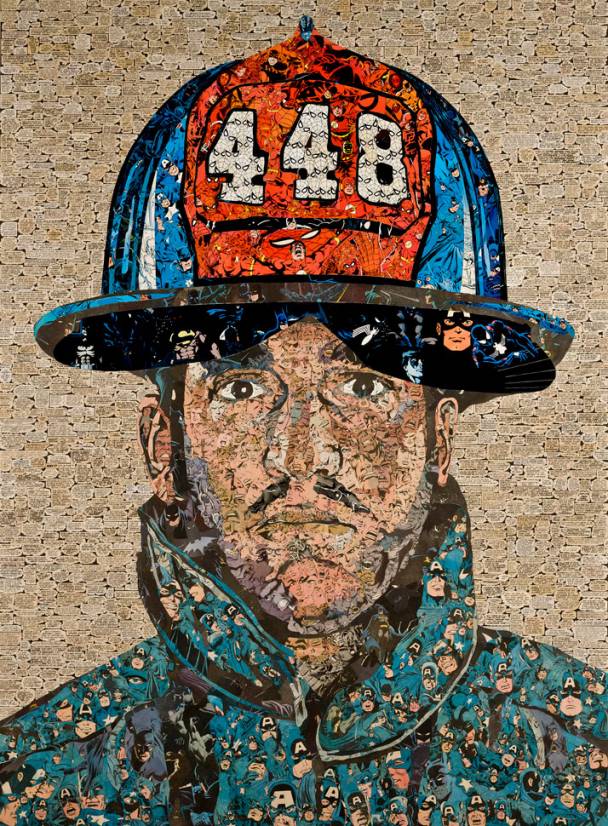

Ben Turnbull’s Real Life Superheroes

This British artist's work serves as a bridge between collective fantasy and the harsh truths of the society we live in.

-

News

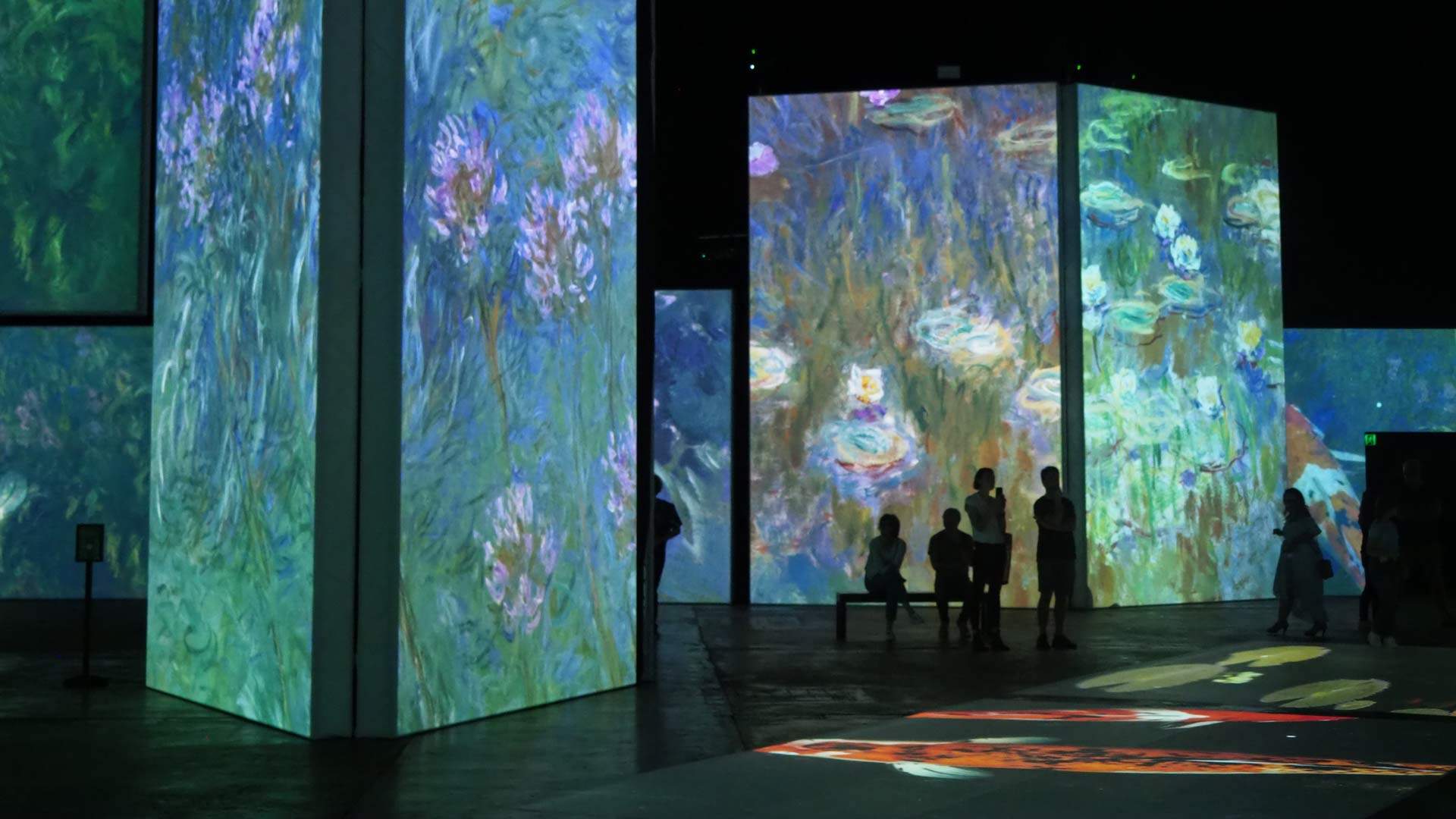

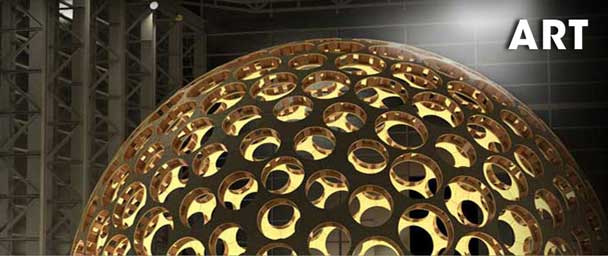

Concrete Playground’s Guide to Sydney Festival 2012

The reinvigorated Sydney Festival has completely transformed our city in summer and it’s made Sydney a truly amazing place to be in January.

-

News

Edinburgh Gardens

With endless grassy lawns canopied by sheltering trees, Edinburgh Gardens caters to a diverse range of picnicgoers.

-

News

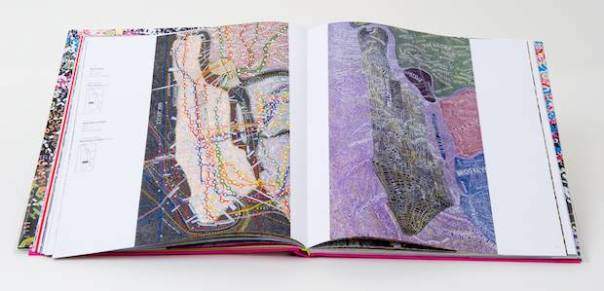

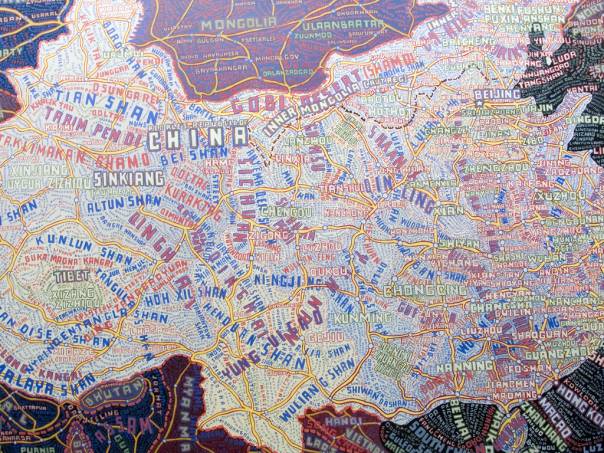

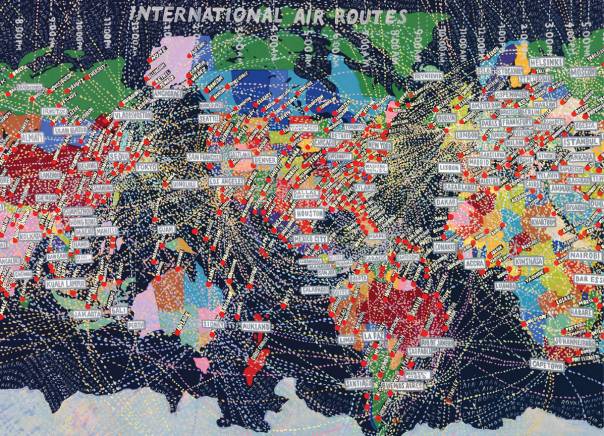

Paula Scher’s Amazing Maps

Scher's pieces offer an individual distortion of the world and strong commentary about our society and often chaotic lifestyles.

-

News

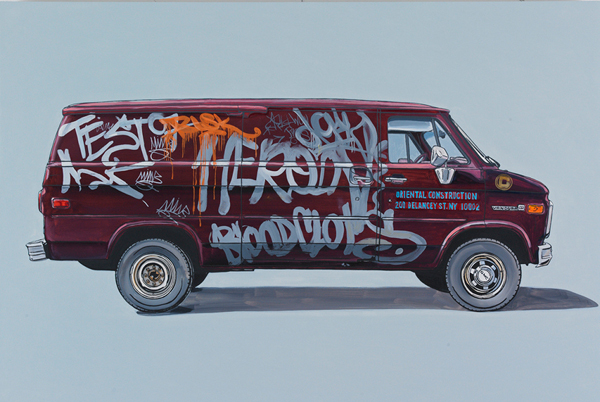

Beautiful Paintings of Graffiti on Vans

New York artist Kevin Cyr paints the artfully graffitied vans and vehicles of his Brooklyn neighbourhood.

-

News

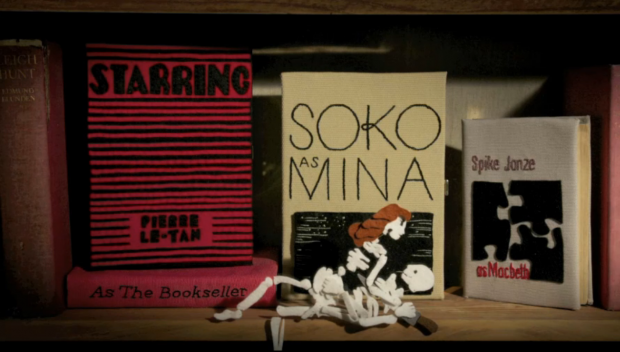

Spike Jonze Directs Stop-Motion Skeletal Love Story

The acclaimed director's latest short film has you falling in love with a pair of horny skeletons who come to life one night in a French bookshop.

-

News

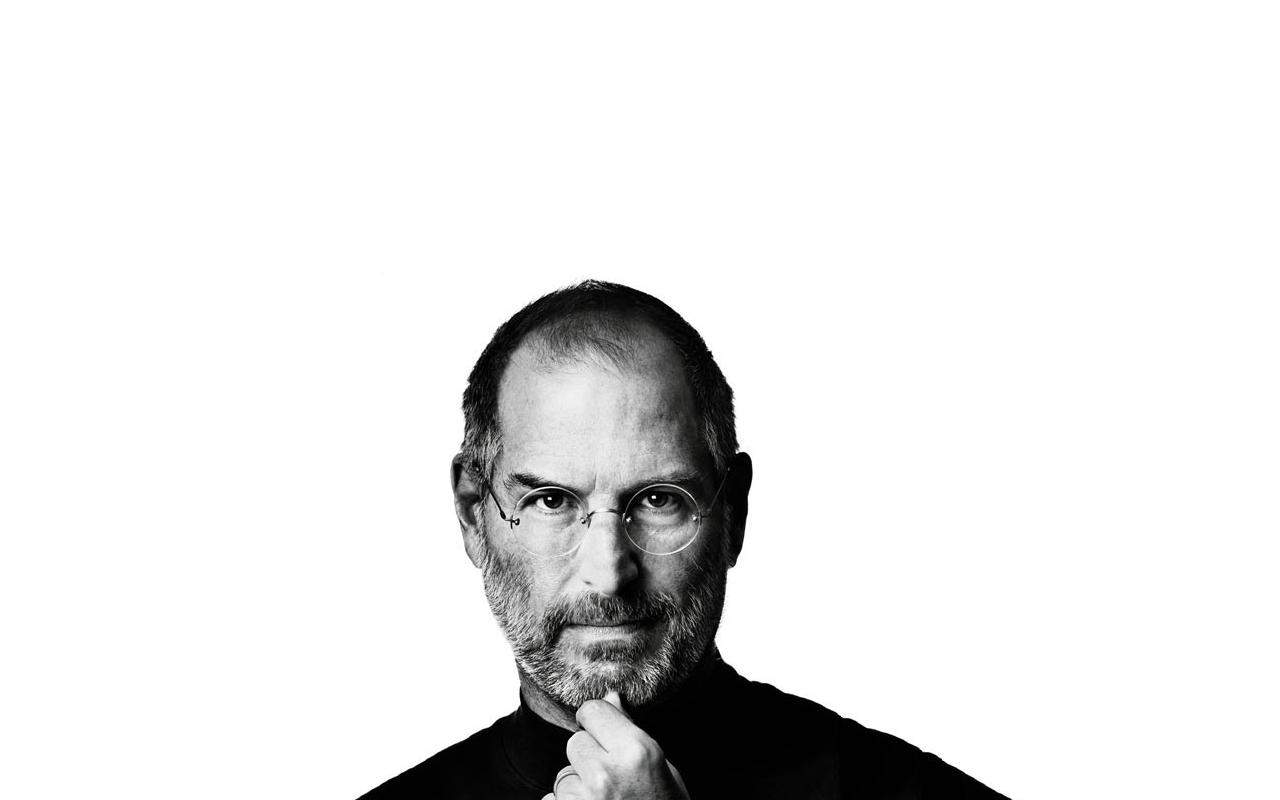

Steve Jobs’ Biographer Interviewed on 60 Minutes

Walter Isaacson shares the story behind the story.

-

-

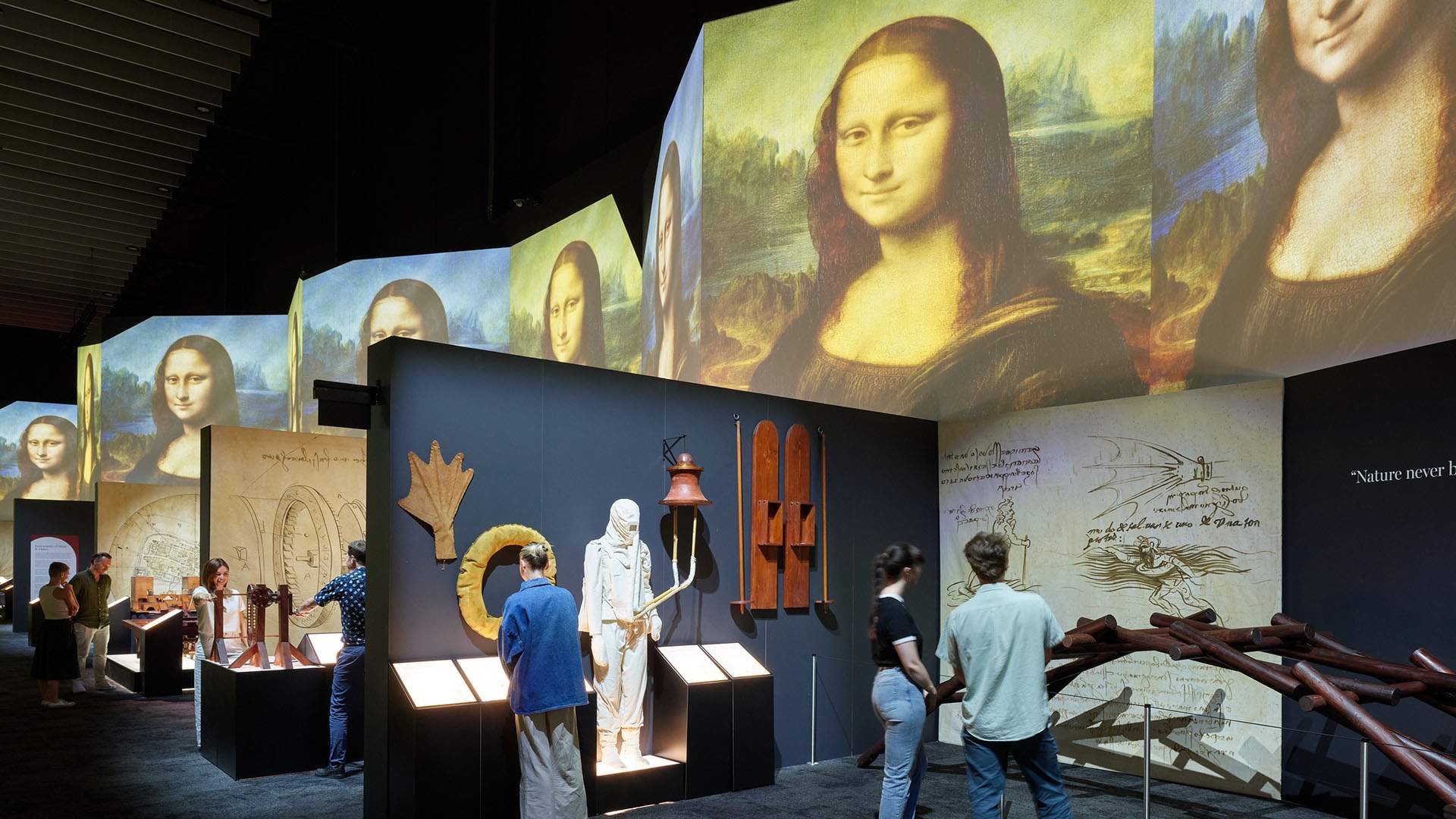

News

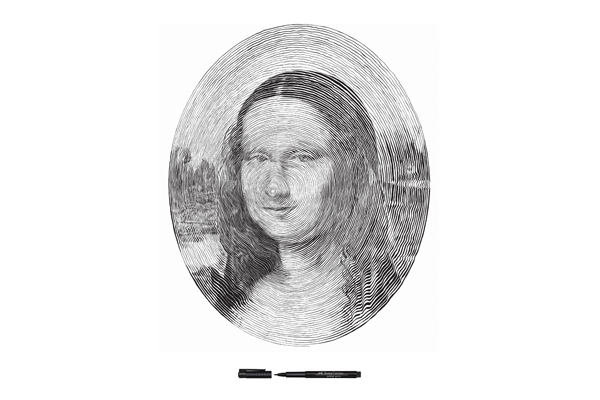

The Mona Lisa Recreated with a Single Line

It's incredible the things an ordinary person can do if they just have the appropriate felt-tip pen.

-

News

Brooklyn Man Turns His Life Into An Exhibition in a Dumpster

In the ultimate act of not being able to let go, an artist has transferred the detritus of his past into a perusable dumpster.

-

News

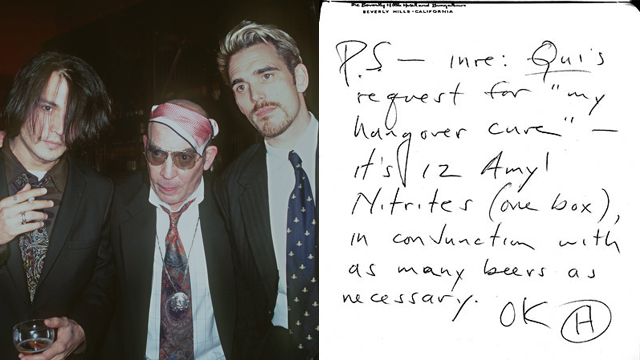

Hunter S. Thompson’s Hangover Cure

The infamous Gonzo journalist has something to cure your throbbing head.

-

News

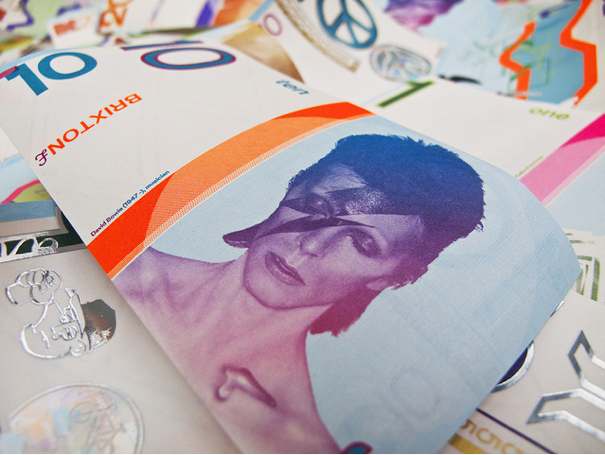

David Bowie’s Face Graces the £10 Note

The face of Ziggy Stardust is now official currency in the London suburb of Brixton.

-

News

Designs That Let You Sleep Anywhere, Anytime

Our society seems to be developing an obsession for sleeping in places that are not our beds.

-

News

Boozy Bears Emerge in South Dakota

Maybe confectionery giants should start selling candy in brown paper bags from now on.

-

News

Win a Double Pass to See Midnight in Paris

Woody Allen’s latest film offers a snapshot of the world’s most adored city in its glory days, where avant-garde intersected with the everyday.

-

News

Concrete Playground Meets Norwegian Wood Director, Tran Anh Hung

We catch up with the acclaimed director ahead of the film's Australia/New Zealand release.

-

News

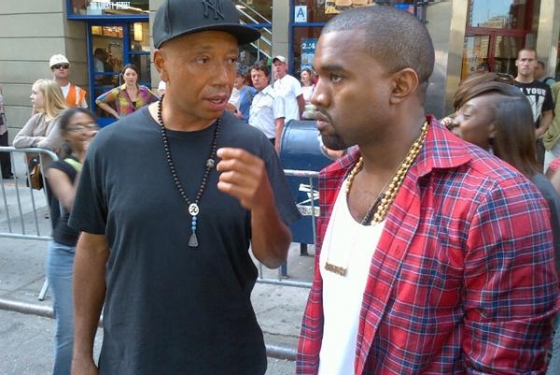

Occupy Wall Street Protests Start to Spread Around the World

How the American Dream has turned into a nightmare for a large proportion of U.S. citizens.

-

News

Feist, Chairlift and Laura Marling to Headline St. Jerome’s Laneway Festival 2012

If you like bands most people haven't heard of, then you will likely love the St. Jerome's Laneway Festival 2012 artist roster.

-

News

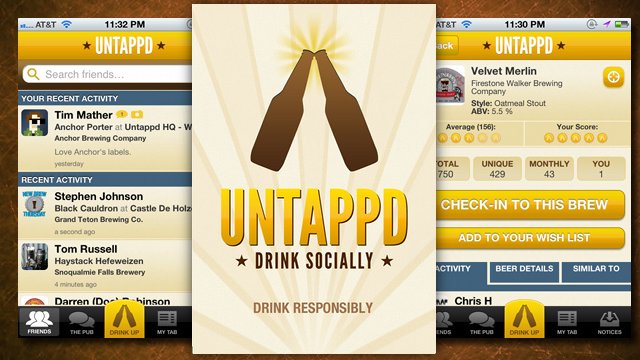

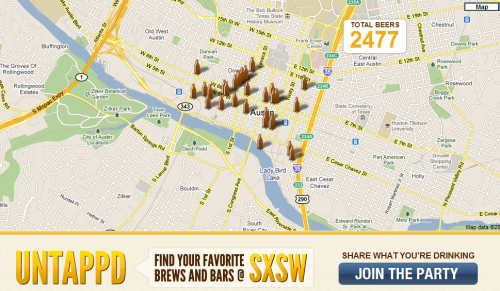

Untappd App Combines Social Networking and Beer

The perfect excuse to drink more beer and check your iPhone.

-

News

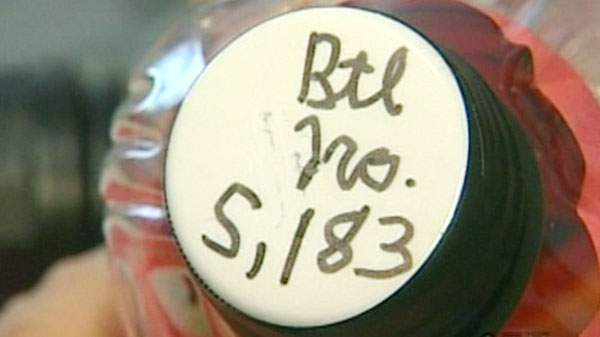

Message in a Bottle: The Unusual Social Network

Harold Hackett has been sending messages all over the world, but unlike most of us he hasn’t been using a phone or a computer.

-

News

Unload Your Emotional Baggage and Get a Free Song in Return

This new site lets you unload your worries to a perfect stranger, who will in turn read it and send you a song they think will make you feel better.

-

News

IPhone Bike Speaker Lets You Listen While You Ride

Play sweet music and use your iPhone as a GPS while riding through the town on your bike.

-

News

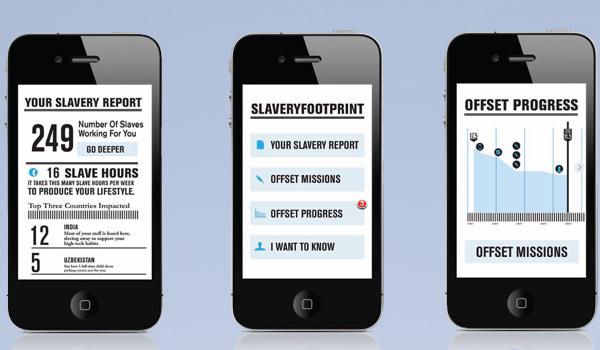

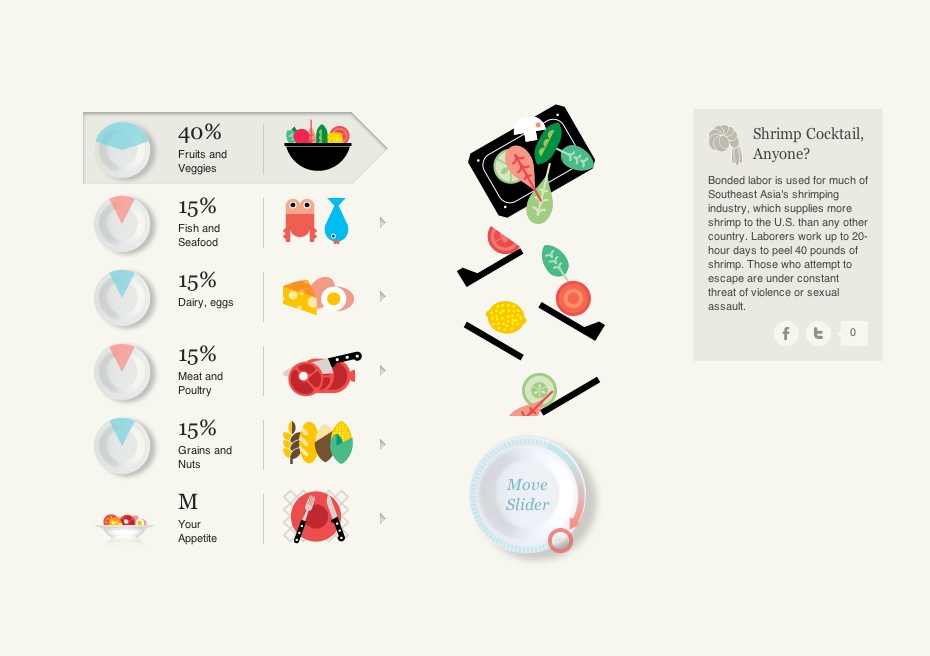

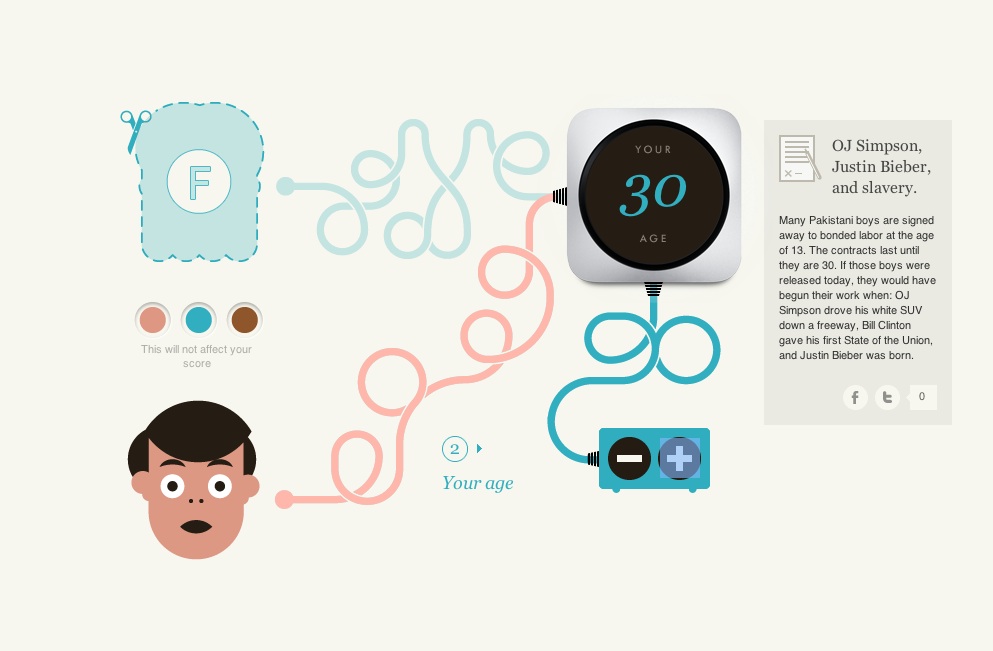

Slavery Footprint: Calculating How Many Forced Labourers Work For You

Cue the bright-eyed, pigtailed offspring of ethical consumerism and social media, Slavery Footprint.

-

News

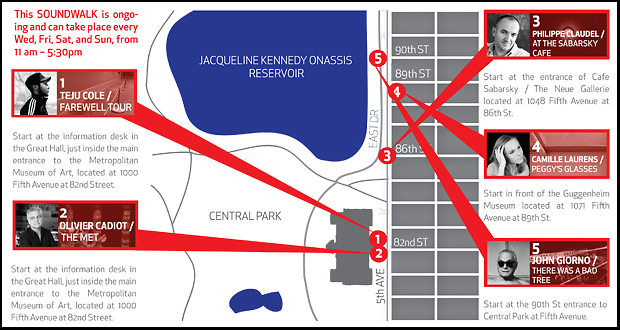

Semi-Fictional Audio Guides Narrate New York’s Museum Mile

A conceptual sound collective and the French join forces to take you for a merry and blissfully confusing journey down Manhattan's Museum Mile.

-

News

Micro-Hotel Sleepbox Makes Being In Transit Appealing

The pod with bed and drop-down desk may mean the days of sleeping in airport food courts are well behind us.

-

News

Win a Double Pass to See The Whistleblower

Based on a true story, The Whistleblower, tells the story of human trafficking in a UN controlled post-war Bosnia.

-

News

Nike Release Back to The Future Sneakers

Nike has released a near-exact replica of the shoes worn by Michael J. Fox in Back to the Future 2.

-

News

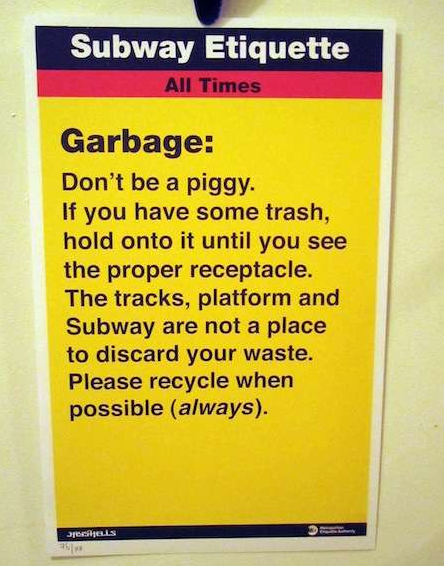

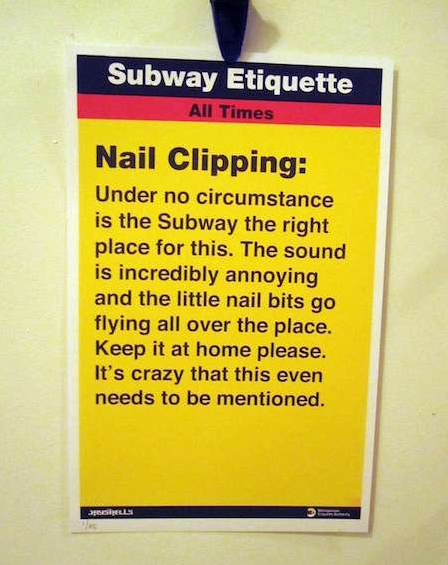

NYC Artist Brings Subway Etiquette to Life

NYC artist Jay Shells' Subway Etiquette Posters pokes fun at commuter pet peeves.

-

News

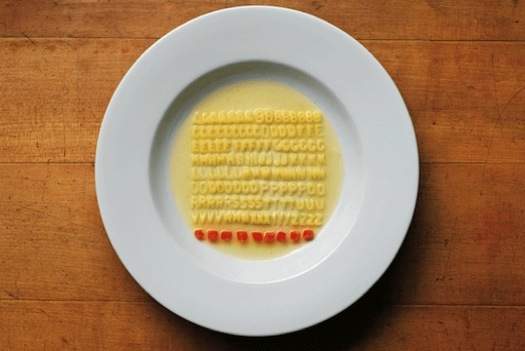

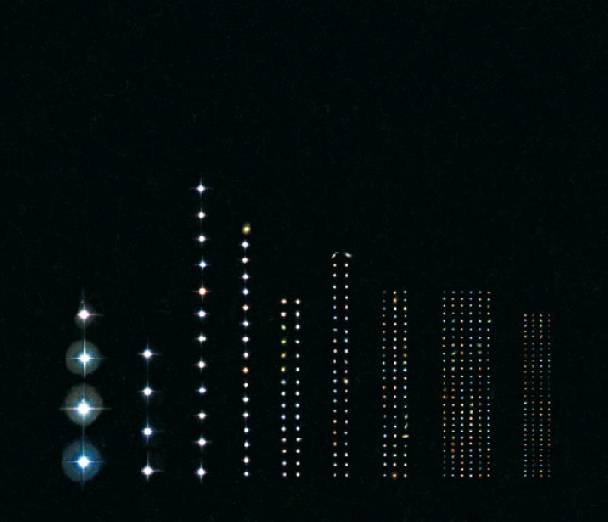

Swiss Artist Injects Order Into the Everyday

Ursus Wehrli wants to put some order into your life.

-

News

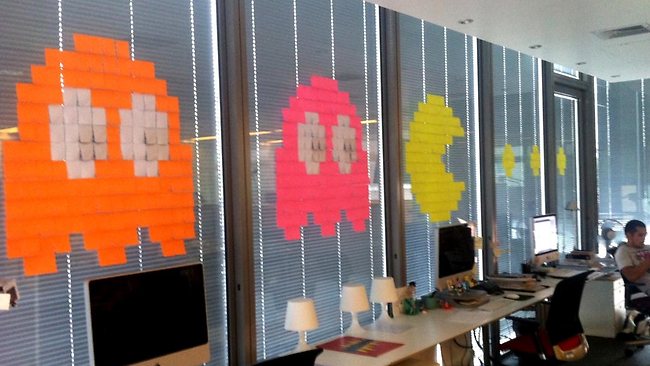

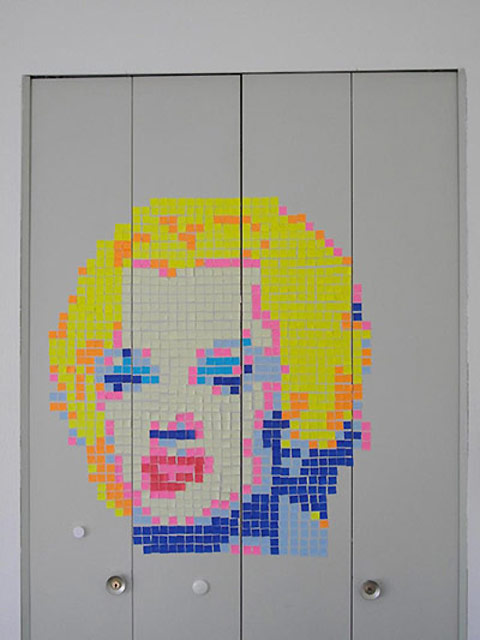

Post-it Note Wars Erupt in Paris

French corporate types are unleashing their creative sides in the French capital.