I, Malvolio

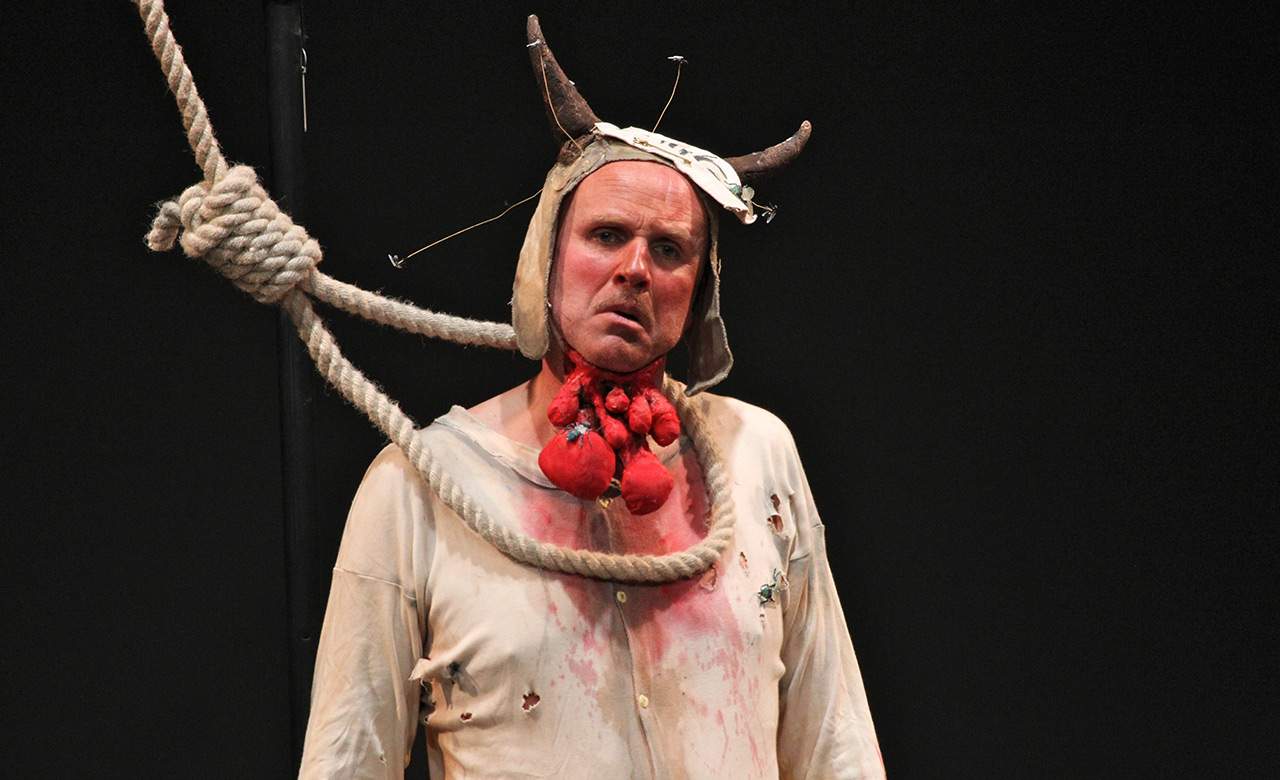

The excellent Tim Crouch gives a Shakespearean underdog a second chance.

Overview

Before he’d even set foot in Australia, Tim Crouch’s work had played to rapturous audiences throughout the country, from Belvoir Street to the Perth, Melbourne and Sydney Festivals. Crouch is an internationally acclaimed theatremaker based in the UK, where he creates his own work as well as directing for the Royal Shakespeare Company, and it’s Shakespeare that’s the subject of his latest show. In his one-man piece at Arts Centre, I, Malvolio, Crouch drags the “notoriously wronged” steward from Twelfth Night out into the limelight.

When I, Malvolio first opened in a Brighton school as part of that city’s festival, Crouch was also asked to make an “adult” version of the same work — now he adapts the piece on the fly in every show, depending on who’s in the house. “If there’s lots of adults the level of interaction becomes more mature and complex, with a younger audience the text changes slightly," he says. "There’s quite a lot of improvisation in this piece, but there’s also quite a lot of strictly scripted words, and it’s in the spaces where the improvisation exists that the piece changes depending on the audience.”

His plays for older audiences typically have a strong ideological bent, pushing against the boundaries of theatre’s capabilities. But he’s found that younger audiences are often more attuned, present and receptive. In this respect, he characterises children and teenagers in a similar way to audiences at festivals, where most if not all of his international work is produced.

“Festivals are melting pots,” says Crouch, “They are meeting points, because work from around the world gathers in those places. Everyone is much more porous — the audience come back at you more deeply.”

I, Malvolio is the fourth in a sequence of five works that began in 2003 with I, Caliban, but Crouch never set out to make a “series”. In these pieces, he liberates characters like Caliban, Banquo and Cinna from the margins of Shakespeare’s plots, letting them take centre stage in their own fluid, transfigured adaptations.

He’s keenly aware of the responsibility these works owe to their “host plays”, but each one is still a freestanding work in its own right. “It’s important that they don’t sit in the shadow of the Shakespeare play they come from; they have to be pieces with their own integrity.”

Crouch believes that this kind of balance allows an Elizabethan playwright’s distinctive voice to resonate with a modern audience, invoking Harold Bloom’s belief in Shakespeare as the inventor of understanding of what it means to be human. “A character like Malvolio is still an archetype that exists in contemporary consciousness,” he says, “and it’s good for a young audience to understand there’s a continuum from that time to now, and how we think about ourselves as human beings. We can still trace our way back.”