20,000 Days on Earth: Truth, Fiction and Never Asking Nick Cave to Do Things Twice

How much of the impossible doco-fiction epic was scripted? The answer may surprise you.

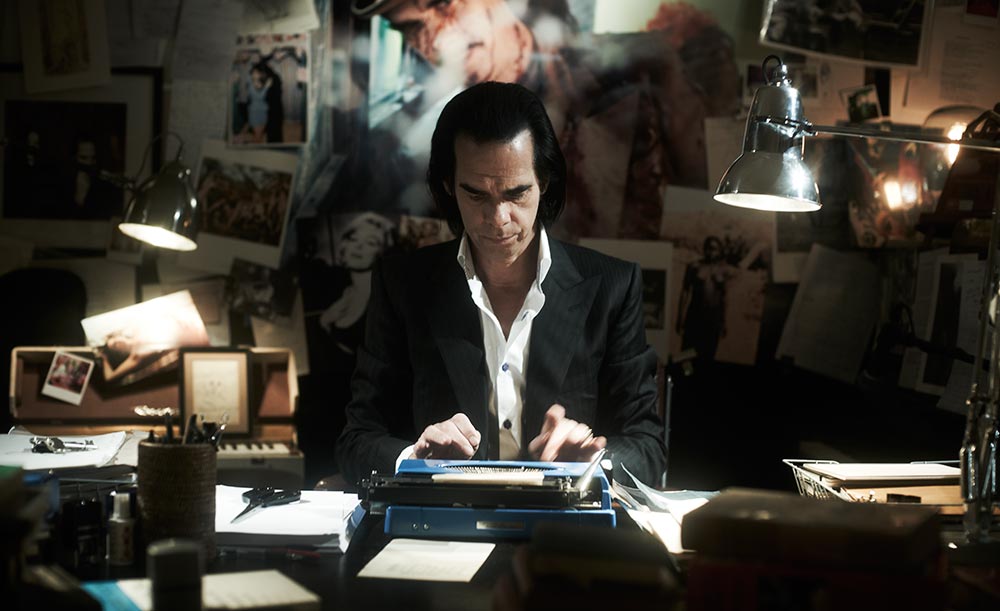

Have you ever seen Nick Cave smile before? It's a shocking thing. For the generations of Australians — and there are many of them — who have grown up with Nick Cave and his Bad Seeds at the centre of musical life, it is startling to realise that amongst the darkness and the tales of addiction, Cave's face can crease itself not into a grimace or a tormented frown but an expression of unguarded joy.

Cave's sudden smile is not the only first for the quasi-documentary 20,000 Days on Earth. Filmmakers Jane Pollard and Iain Forsyth have made a documentary that plays like a narrative but feels like a video clip. Unlike its obvious fictional music-doco predecessor This Is Spinal Tap, the duo's film is not a stealthy takedown: they're playing for real. Partly this is because the filmmaking team are artists with a 20-year partnership of making work together. Without any of the film world's preconceived ideas of what constitutes a documentary, their artistic training has allowed them to craft something out of elements that others would see as disparate and incompatible. And partly it's because Nick Cave's life and music necessitates a different approach to making documentaries. An artist as unconventional as Cave requires the defiance of filmmaking conventions.

After opening Sydney Film Festival in June, 20,000 Days is now in art-house cinemas for everyone — including two very special sessions at Melbourne's Astor where Cave will be appearing in person for a Q&A. We spoke to Pollard and Forsyth about what it means to make a hybrid music documentary, the process behind the beauty and what Nick Cave is really all about.

This is a documentary that blurs some serious lines between genres and fiction and what we think we know as documentary. What exactly was scripted and what flowed organically? Cave himself is credited as a writer.

Pollard: No dialogue was scripted at all. Apart from one line [preceding Cave's meeting with a therapist, Darian Leader], the psychoanalyst's assistant says, "Darian will see you now." The things that Nick wrote were all the voiceovers, with that particular tone. Some of those things came pre-written, we found them in his notebooks, like the first quote we used: "At the end of the twentieth century, I work, I write, I eat…" — that was a lyric from his notebooks. Then we we asked him to expand on those notes. We sent him about twenty, thirty topics for the voiceovers, and when he was on tour he'd write a paragraph and send it back. And if we thought it was worth recording, we'd get him to record it on his iPhone and just try it in different places in the film.

I understand you didn't actually set out to make a doco about Nick Cave. How did this project start and evolve?

Pollard: We'd filmed the scenes of Nick and Warren [Ellis] writing and demoing the album, and then the band in the studios. And we'd filmed all of that before we knew what it was we were going to make this into. The big scene in the film is them playing live from the album 'Push Back the Sky'.

At that point we knew we had something that deserved to be carried in something much bigger than the scope of a contemporary music film or a promo that would end up on YouTube and sync very quickly. We wanted to make something bigger that would be more meaningful and stand the test of time, and that's when Iain and I wrote an action script. We knew we had two things we wanted to do, we had the cycle of the album, and then more specifically the individual song — that's the first thing you hear, the song 'Jubilee Street', and then the performance on the Sydney Opera House stage. So we had that cycle as one parallel for the storyline.

The other cycle came from finding the film's title in Nick's notebook - it was a discarded song, and he'd done this calculation of how long he'd been on earth. We loved the phrase 'twenty thousand days on earth' and it gave us a very simple conceit to strap the rest of the film onto. So we thought, okay, let's make the film one day on earth. And then we can make whatever we want happen on that day. Everything that happened in that day was something we decided. We wrote the parameters of it, and Nick worked with us. He'd say, 'I'm not so sure about waking up in bed with my wife; I'll give it a go, but I might not be happy with that.' He kinda just cast his eye over what we wrote and said 'I'll give it a shot'. For us, that's where we decided to start.

Cave talks a lot about the intersection of living in a story and telling a story. I really can't tell where the boundaries are with your film. Where did you guys draw these boundaries?

Pollard: We set ourselves certain parameters. One rule was, we'd never ask Nick to do something twice. Even if he said something and it was great, but we didn't catch it or the camera wasn't on, we wouldn't ask him to do it again. He never had to flip from that headspace of being in the moment, to suddenly remembering the act of what we were doing which was making a film. And with Darian, we met him a few times, we gave him a set of topics, he read books and novels, and we gave him some structure. He had an idea of the sorts of things we were looking for. And then it became an endurance thing that we filmed for ten hours. There's a disorientating thing for both Darian and Nick, talking and not knowing what we would use.

Forsyth: With Darian, the psychoanalyst, it was a totally artificial location. Darian is a professional psychoanalyst, that's what he does. Our cameras were out of Nick's sightline, all the technical side of filmmaking was hidden, so as much as possible, it would feel like a genuinely intimate conversation. They met for the first time on set.

How do you negotiate these funny blurred lines in hybrid documentaries like this? How do you ensure you create something that's real and true and still semi-scripted?

Pollard: It's a very simple thing: if we can physiologically feel an emotional truth in a scene, then that's the truth we're interested in. Whether it's factual or autobiographical, you still need to feel an emotional truth. [Had we only taken a strictly observational approach], it's a narrow road to take your story down, because suddenly it becomes tied and tent-pegged by things that are outside of it, outside its control and parameters and you'll inevitably have to break those parameters, as every reality program does. Everything we see that presents itself as factual or observational is flawed in the truth that it's telling, the actual truth that it's telling. I think the audience is sophisticated enough to get it. I just never doubt that an audience is going to stay with us.

In your film, Cave talks a lot about his fear of being forgotten. As someone who's gone to art school and knows a lot of people who also have this fear, I'm not sure how I feel about it. Do you think it's intrinsically egotistical to want artistic immortality? Or is it a natural inclination for an artist?

Pollard: I think anybody who has, as their job, put themselves into performing and creating something bigger than themselves, something that is about being remarkable and being on show and being a spectacle … to be a spectacle but not to be remembered? That's a tough dichotomy. His reason for existence is to be remarkable, to be the centre of something, to be spectacular and to entertain.

Forsyth: If the question was, 'are you concerned about not making a difference?', that would be completely agreeable. As an artist, as a filmmaker, you want to be impactful.

20,000 Days on Earth is in select cinemas nationally, and also showing at some special screenings. The most special of these is probably Friday, December 19, at Melbourne's Astor Theatre, when Nick Cave will appear in person for a Q&A. More info and tickets on the Astor website.