When Nicolas Cage and Ozploitation Combine in a Sun-Scorched Psychological Thriller: Julian McMahon and Lorcan Finnegan Talk 'The Surfer'

This Western Australia-shot movie boasts an inimitable American star, an Australian actor with decades of overseas success and an Irish filmmaker bringing an outsider perspective on Aussie localism.

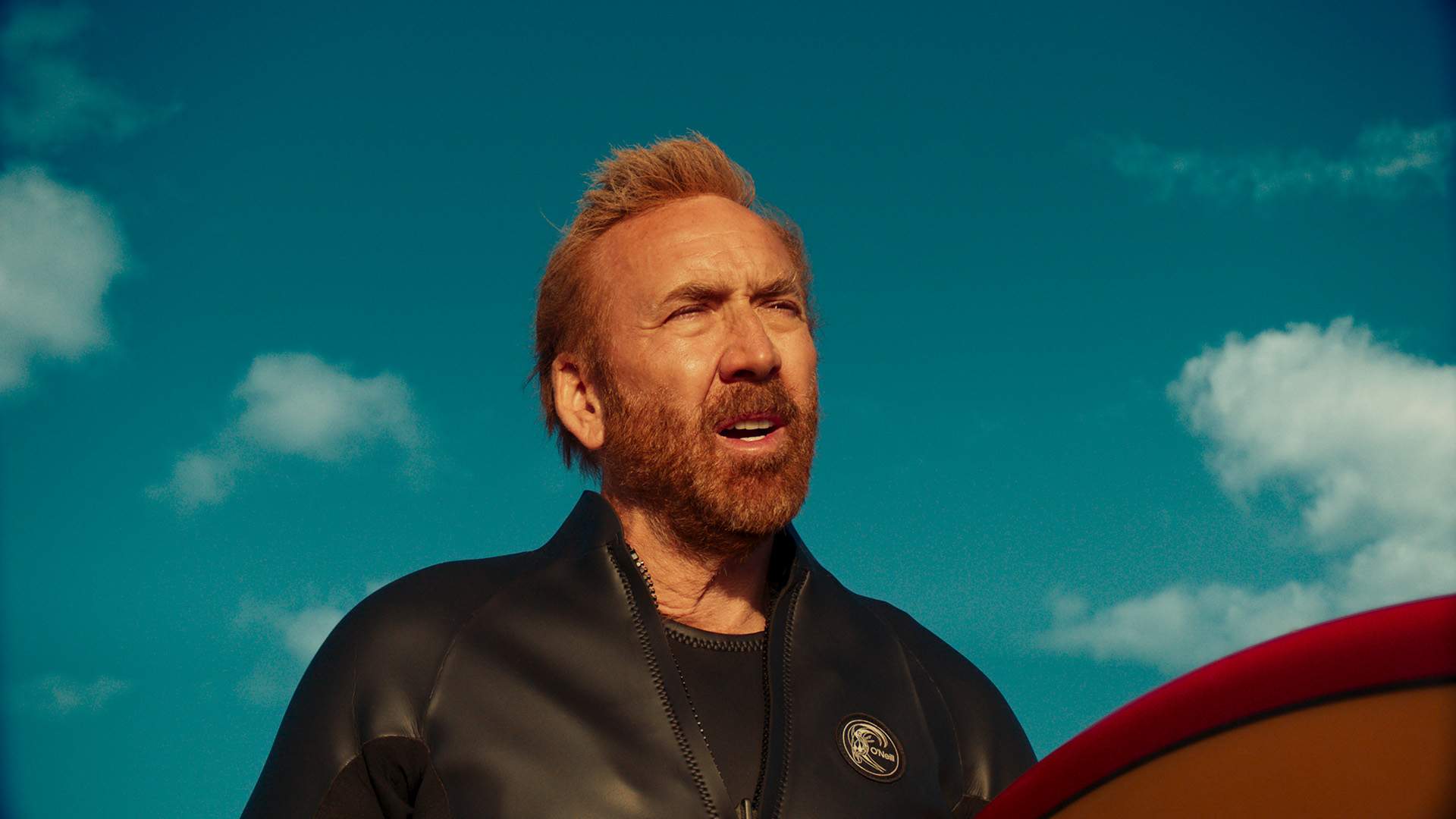

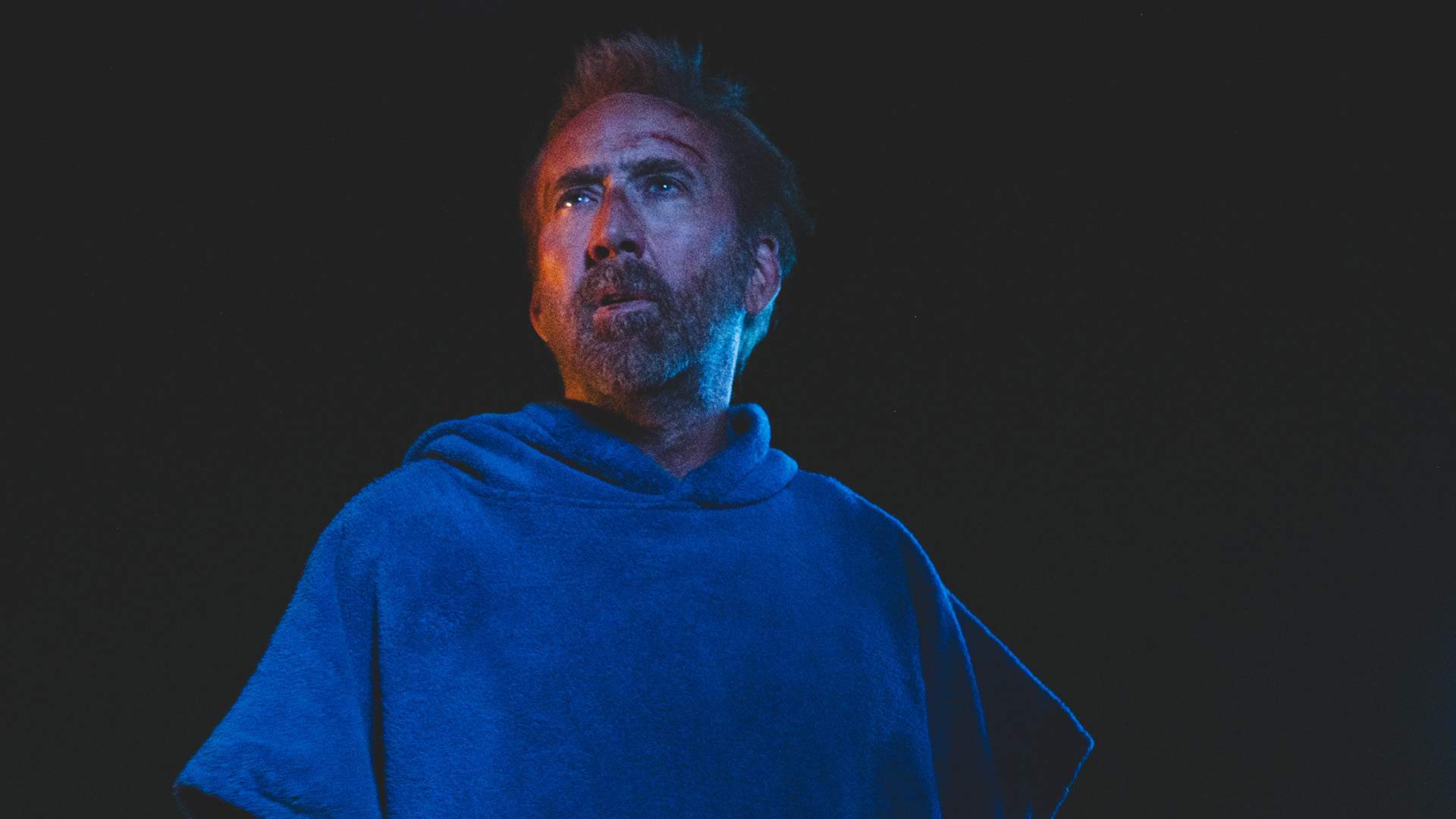

"It wasn't so much about antagonising Nicolas Cage, for me," Julian McMahon tells Concrete Playground. "It was more about getting him to face his demons — to truly look at himself and evaluate who he has been in life, who he is now and who does he truly want to become?" That's how the Australian actor describes his task in The Surfer, in which he stars opposite the inimitable Cage (Longlegs) in the latest film to ride the Ozploitation wave. The two portray men caught in a battle at a scenic Australian beach. Cage's eponymous figure is an Aussie expat returning home after living in the US since he was a teen, and is fixated upon purchasing his old childhood house as the ultimate existence-fixing dream. McMahon (The Residence) is Scally, the local Luna Bay surf guru who decrees who can and can't enjoy the sand and sea, complete with a band of dedicated disciples enforcing his decisions — and who doesn't give the besuited, Lexus-driving, phone-addicted blow-in a warm welcome.

It was true when the trailer for The Surfer arrived and it remains that way after watching the full film: Wake in Fright-meets-Point Break parallels flow easily. Director Lorcan Finnegan (Nocebo) and screenwriter Thomas Martin (Prime Target), both Irish, are purposefully floating in the former's wash, adding a 2020s-era Ozploitation flick with an outsider perspective to the Aussie-set canon, just as Canada's Ted Kotcheff did with his 1971 masterpiece — and as British filmmaker Nicolas Roeg similarly achieved with Walkabout the same year (the two premiered within days of each other in competition at Cannes). With Point Break, though, if the OG version was instead about a middle-aged man returning home rather than an FBI agent chasing bankrobbers, and if that character found himself taunted by rather than accepted into the crew that rules its specific coastal turf, then that'd be The Surfer's starting point.

Adding to a resume that's seen him use jiu-jitsu against alien invaders (Jiu-Jitsu), voice a prehistoric patriarch (The Croods: A New Age), battle demonic animatronics (Willy's Wonderland), hunt down the folks who kidnapped his porcine pet (Pig), step into his own IRL shoes (The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent), get his gunslinger on (The Old Way), give Dracula a comic bite (Renfield), don Superman's cape (The Flash), pop up in people's dreams (Dream Scenario), face the end of the world (Arcadian) and turn serial killer (Longlegs) in the 2020s so far alone — alongside more roles — Cage begins The Surfer waxing lyrical about the pull and power of the waves, including their origins, plus the result when you attempt to conquer them. "You ever surf it or you get wiped out," the film's protagonist, solely credited as The Surfer, tells his high school-aged boy (Finn Little, Yellowstone) as they approach his preferred patch of oceanside paradise. "Locals only" is the response from Scally's gang, however, when the father-son duo head to the water, but that isn't a viewpoint that The Surfer can roll with.

The Yallingup, Western Australia-shot movie, which itself debuted at Cannes in 2024, is then firmly a Finnegan flick as its namesake gets caught in a nightmare under the blazing sun courtesy of a few simple decisions, and equally thrust into an experience that questions reality. The director has made four features in nine years: 2016's Without Name, 2019's Vivarium, 2022's Nocebo and now The Surfer. In every one, the lead is plunged into a type of purgatory or hell. The first also sets its protagonist against the elements at times. Trying to buy a house equally turns surreal in the second. The past haunts, too, in the third. All four have more than a little time for peering at the trees as well.

Asked what interests him about making psychological thrillers in this mould, Lorcan responds "good question: is there something wrong with me?". He continues: "I think it arrives, from a filmmaking point of view, because it allows a lot of creative freedom — because if you're delving into somebody's mind and their experience and their interpretation of events and reality from a very subjective point of view, it really allows a certain amount of elasticity in terms of visualising that and interpreting that for the audience, and for the audience to almost feel like the character feels entering into that world. Particularly with this film, because it's such a subjective experience for Nic Cage's character. And the audience goes on that journey with him and discovers what he discovers and feels what he feels — and starts tripping out when he's tripping out. So it's a weird experience."

McMahon was familiar with Finnegan's output when he signed on for The Surfer. What appealed to him about this project? "I think, in this particular case, it was how well-written the entire piece was," he advises. "That, accompanied with Lorcan's previous films, is a recipe for a well-earned match; they fit each other perfectly. And regarding his approach to psychological thrillers, I was intrigued by his novel and unique vision of this piece. His movies are like something I've never seen before, and that is inspiring." Did Finnegan's penchant for toying with reality influence how McMahon tackled portraying Scally — a character who is so key in the feature's querying of what's genuine and what's all in The Surfer's head? " I think you leave that up to the filmmaker," he notes. "Play your part and allow him, Lorcan, to create the sense of reality."

In 2025, audiences are witnessing McMahon at two different extremes when it comes to portraying Australian characters — first as the Aussie Prime Minister in Netflix murder-mystery dramedy The Residence, and now as Scally here, with The Surfer in local cinemas since Thursday, May 15 before heading to streaming via Stan from Sunday, June 15. "I'm looking for variety. I'm looking for characters that allow me to feel challenged, maybe even a little uncomfortable," he shares. Only The Surfer brings him back to Aussie films for the first time since 2018's Swinging Safari, though, after spending much of his career working internationally (see: Profiler, Charmed, Nip/Tuck, the two 00s Fantastic Four movies, the FBI franchise and plenty more). "I love working in Australia; however, it's more about the piece and the characters I'd like to play," McMahon reflects.

An American star who couldn't be more unique on-screen, an Australian actor with decades of overseas success, two Irish friends and filmmakers layering an outsider vantage onto Aussie localism, nodding to Ozploitation classics, taking inspiration from 1968 American great The Swimmer, digging into masculinity and materialism alongside identity and belonging: it all adds up to mesmerising viewing. Somehow, as prolific and wide-ranging as Cage's filmography is, putting him in this beachside scenario wasn't already on his resume, but he gives it the full glorious Cage treatment. His energy is pivotal to the movie, as it was to McMahon and Finnegan as his co-star and director, respectively — which we also chatted to the pair about, plus everything from trapping characters and humanity's yearning to belong to quintessential Aussie beaches and recurring themes in Australian cinema.

On Why Being Just One or Two Decisions Away From Getting Stuck in Your Own Purgatory, Losing Everything or Both Fascinates Finnegan

Lorcan: "I suppose we're all like that, really. We're all a couple of steps away from losing it. And I think a lot of the time, the characters in my films are trapped in some way, whether that's in a physical place or mentally, or in their behaviours or relationships, whatever.

It's something universal, though, that we all feel we're trapped in some way — whether that's with our routine or jobs or lives or physically inside, like a fleshy trap of meat and the only release is death.

I suppose all of that is quite existential and fascinating. And in some ways, films are a reflection of our subconscious. Stories reflect our inner fears, and going crazy and all that kind of thing. So, to me, it's just fascinating to explore all that."

On What Excited McMahon About Collaborating with Nicolas Cage — and About Stepping Into Scally's Shoes

Julian: "I've been an admirer of Nicolas' since as long as I can remember. His work is always entertaining, inspiring and unique. I also really love the energy that he puts into everything that he does. And I was excited to develop a character that would fit well with his on-screen persona as The Surfer.

There's a few things you need to accomplish in fulfilling the character of Scally. You need to fill the requirements of the movie itself, and what it is asking from your particular character, and as an entire piece. You need to develop the relationship between Nicolas' character, as well as all the other characters. And then you need to be sure that you are filling the requirements of who Scally truly is.

With Scally, there was no room to waiver — the more definitive he was, the more strength he had. And I thought that was particularly important."

On Why Taking Inspiration From The Swimmer and Ozploitation, Then Digging Into Ideas of Masculinity, Materialism, Belonging and Identity — in Australia, as an Irish Filmmaker with an Irish Screenwriter — Appealed to Finnegan

Lorcan: "When I read the outline, what struck me was it was going to be about this man of a certain age, at a certain point in his life, where he'd amassed success, I suppose — what would be deemed success. He has a nice car. He has his suits. He's got some money. And he wants this one last thing, to buy back his family home, and then that will fix all of the problems that are manifesting over the years.

So his relationship with his wife has fallen apart. His son has no interest spending any time with him. But he still thinks 'if I just have this one thing, if I can just buy this house, that will fix everything'.

But then, of course, over the course of a few days he loses everything bit by bit — all his material wealth, his watch, his phone, his shoes, his suit, his car. And it's like he needed to shed all of that in order to actually, almost like therapy or something, to actually find what it is that he needs as opposed to what he believed he wanted. So that just fascinated me as a way into a story.

And then both Tom and I have a love of New Wave Australian film. And then we were talking about the tradition of non-Australians, with Ted Kotcheff being Canadian and Nic Roeg being British, non-Australian filmmakers making a film in Australia as the outsider view — and this could be a continuation of that, because there hadn't been, from our point of view, there hasn't really been any of those kinds of films in a long time coming out of Australia. So we wanted to go and make one. And this was the perfect vehicle, basically."

On Making a 2020s-Era Take on Exploitation with an Outsider Perspective, as 70s Greats Wake in Fright and Walkabout Did Half a Century Ago

Julian: "This story could take place in many locations around the world. It could also be embedded in many different types of developed societal cultures. It could be California, could be Hawaii, could be the UK and places around Europe.

I think what's interesting to note is that this particular surf culture can be found, almost identical, anywhere in the world."

Lorcan: "All of the themes around identity linked to place — and also Cage's character being an outsider, that was sort of our way in, really, or my way in, particularly in terms of thinking about how to direct a film like this. Because he's an outsider returning to a place that he hasn't been in over 40 years.

He's lost his accent, and he's got this weird, nostalgic, rose-tinted-glasses view of the place from his childhood. So it's almost like he remembers it from the 70s. So that was the way of making it, the look and feel of the place, that it's all from his weird point of view.

Ozploitation films from that period, there would always be these very masculine men drinking beer, Broken Hill-style. So we were updating all of that, though, to show the surf community.

But they're not just like Point Break surfers. These guys are all the doctors, hedge-fund managers, wealthy yuppies. Julian McMahon's character, he plays this guy Scally, who's almost like a weird shaman version of a Joe Rogan or Jordan Peterson kind of guy, who's lecturing these younger guys on masculinity — and they could be tribal and animalistic down below on the beach, but when you're up above, you behave differently.

So all of that felt like perfect updates of previous themes around masculinity in these Australian films from the 60s and 70s, and even 80s — to update it now in a much more contemporary way, talking about masculinity, but it is still classic examination of it in a way."

On Why Nicolas Cage Was The Surfer's Eponymous Figure to Finnegan — and Getting Him Onboard

Lorcan: "I remember reading the script through from beginning to end before we offered it to him, imagining him in every scene. And I just thought he'd perfect, because there's not that many people who can play drama, action, comedy, all of these things, and have this physicality to the performance that Nic can do.

So once he came onboard, it made The Surfer's character come to life, in a way. Also, as we were shooting it, we were finding that we were seeing the humour of these scenes bubbling up, too — which is good fun, because Nic's funny.

He'd seen the previous film of mine, Vivarium, which he liked. And so when he got the script, he was already familiar with the filmmaker, which was helpful. And then he loved the title The Surfer, he told me recently — that was one of the things, because he grew up in California and he's familiar with surf culture, and thought that was intriguing.

And he read the script and he just really liked the material. He thought it had a kind of Kafka-esque kind of vibe to it, and the character would be very challenging to play. And then he also loved the idea of going off to a little town Australia to make this film, the adventure that would bring."

On McMahon Approaching Scally and His Offsiders in Terms of Them Trying to Find Their Way — and How Else He Built the Character On-Screen

Julian: "I wanted to let Scally evolve in his own manner. And so while I was developing the character, I put no restrictions, thoughts or preconceived ideas that I might usually put into the development of a character, and let it come to me.

It was an interesting approach, and what it allowed for was development right up until the end of shooting. Most of Scally was developed on set, in the environment, with all the other players present, your director and, of course, the largely influential location.

I decided to not research anything, to just allow the character to speak to me from the written word on the page. I gave myself no limitations, no boundaries and the ability to feel comfortable with not really knowing exactly what I was doing all the time.

I wanted to be more willing to allow the time and space of the moment to fill the development of the character."

On the Energy That You Get From a Nicolas Cage Performance When You're Working with Him — Both as an Actor and as a Director

Julian: "That is one of the reasons I looked at this as a great opportunity to challenge my own concept of performance. I love the energy that Nicolas brings to his work.

And now the question is 'how do I contrast that energy, that delivery, that performance, so that when we see the two of them on screen, we know that we are dealing with two completely different individuals? And then let that play?'.

Lorcan: "A lot of it is in conversation before shooting. We talk about scenes, we talk about what point he's going to — his character changes, his voice changes at certain points in the film, and he's hobbled at certain points of film, then his foot gets a little better, all those sort of things were tracked in prep.

And then, when we're shooting, in terms of directing, a lot of the time it was just Nic — so we could do silent movie-style directing.

The scene where he completely breaks down and he's crying, sobbing, and then that turns into rage — shooting that, we're shooting on the long lens, slowly zooming in on him. And then I'd be saying 'you've lost everything, you're crying, everything's falling apart, you're never going to get the house'. And you're like 'and now you're starting to get angry, you're getting angrier, you snap'.

And he loves that actually, being directed off-camera, and he can just give that performance and time it to the movement of the camera then as well.

So all that was really good fun. But I think there was an element of trust between us as well, that he trusted that I just use all the best pieces to put it together in the edit, which allowed him the freedom to give a few different types of performance throughout the film — that we would just use the best of."

On Finding a Balance of Charisma and Menace for Scally — and Digging Into Humanity's Yearning to Belong, and the Rules and Hierarchies That We're Willing to Enforce and Abide to, Along the Way

Julian: "There may not be a perfect balance — and I believe, quite definitively, that there is no real way to play charisma, and then perhaps menace.

He is who he is and he does what he does, and it's up to the viewer's discretion as to how that should be interpreted. Being present to each moment would be my only way to find balance.

Scally has his own discomforts, and he is very much still finding his way. Even though he would never expose that side of himself, he knows he's a work in progress.

Scally's position is one of such that if he waivers, it is very likely that he will lose the love and devotion of those who see him as someone worth listening to, someone worthy of following."

On Finding the Exact Right Quintessential Australian Beach for the One-Location Film

Lorcan: "That was the biggest challenge. And actually, although it might seem like it — and I thought the same, 'oh yeah, there will there be loads of them' — it was really hard to find a car park that's raised quite high above the beach with a view down, and the beach being a certain scale, and all that kind of thing.

We settled on Western Australia early on, which is obviously, as you know, it's gigantic — it's not exactly a small place. And we scouted north of Perth, as far as Kalbarri, I think. And then we scouted south of Perth. And, actually I think Yallingup was the last place we stopped when we were going south.

And as soon as I saw it — I first saw the beach, and I thought it looked perfect, that kind of crystalline turquoise water which is very evocative of memories and dreams. And this golden sand. And then the car park above it was perfect size, and surrounded by bush. There's a national park area right behind it. And then it has a great vantage point, like a viewpoint down to the beach.

So it has all the elements. So we're trying to match the staging of the script to the location. And then once we found the location that was perfect for the film, we tweaked the script to match it better as well.

But it's harder than you think to find this sort of car park that is perched above a beautiful beach‚ with good surf as well. Nice breaks. And Western Australia, as well, has these amazing sunsets, that you get this really long twilight kind of lighting, which we took advantage of as well."

On Why Localism, Plus the Manifestations of Masculinity and Aggression That Can Come with It, Are Common Themes in Australian Cinema

Julian: "That's a tricky one to answer. I guess the simplest answer would be that Australian cinema is still challenged by those concepts, and is perhaps looking for a way to flush that out and understand it.

That said, if you've read anything from Thomas Martin, he very specifically notes that his ideas and concepts were developed in many places. Californian surf culture was a heavy influence, as an example."

Lorcan: "I suppose Western Australia, anyway, still has a very masculine kind of energy to it. I think it's because it's a lot of mining, a lot of very physical jobs that men perform there. And they can also make a lot of money very quickly, and then also lose it very quickly. It's one of the most-remote cities of the world — the most-remote city in the world — Perth, isn't it?

And so I think although Australia has changed a lot since the 70s, in terms of becoming more liberal, I suppose, and less chaotic, there's still elements of that. And it was interesting to see the culture between, even from Perth down to Margaret River. Margaret River is a beautiful wine region and everyone was actually really welcoming — and there's a winery called Bacchus Family, who invited the entire crew up to their estate, their vineyard, and wined and dined us.

And I suppose, this is similar to Ireland, in a way. Ireland has sort of grown in parallel with Australia, in terms of we used to be very Catholic, and there was a very kind of patriarchy in Ireland, that still exists but has evolved over the years. And I feel like it's the same with Australia. But there's still interesting things — like the way that masculinity has evolved over the years has almost come full-circle. Now there's these guys who are lost and looking for something, looking for belonging. And that whole male cult is forming around the world, I think, not even just Australia."

The Surfer released in Australian cinemas on Thursday, May 15, 2025, then streams via Stan from Sunday, June 15, 2025.

Images: David Dare Parker / Radek Ladczuk.