Unpacking the Reality of Mumbai Life for Women in a Cannes Award-Winner: Payal Kapadia Chats 'All We Imagine as Light'

With her fictional feature debut, this Indian filmmaker has earned a Best Director Golden Globe nomination and made Barack Obama's list of favourite movies for 2024.

Filmmakers frequently trade in dreams and reality, plus the space where the two meet, clash and contrast. Directing a movie that's steeped in the daily actuality of being a woman in Mumbai, Payal Kapadia does exactly that with her first fictional feature. In All We Imagine as Light, three nurses go about their lives in India's most-populous city — big-smoke existences that appear independent, but are dictated by patriarchal societal norms, class and religious stratifications, and the growing gentrification of the nation's financial capital. Making the leap from documentary to narrative films after 2021's A Night of Knowing Nothing, Kapadia sees her characters' plights with clear eyes. Her 2024 Cannes Grand Prix-winning picture isn't afraid to embrace their hopes and desires, however, or to be romantic and poetic as well as infuriated and impassioned.

Head nurse Prabha (Kani Kusruti, Maharani), her younger colleague and roommate Anu (Divya Prabha, Family), and their elder co-worker Parvaty (Chhaya Kadam, Snow Flower) all seem to be enjoying their own paths. In everything from where they live to who they love, though, their choices aren't completely their own. Hailing from Kerala, Prabha is married to a husband that she barely met before they wed, and who now works abroad in Germany. As she tends to the wounds and helps with the woes of others, the life that she so desperately wanted has failed to come to fruition. While fellow Malayali nurse Anu is carefree and in love, her boyfriend Shiaz (Hridhu Haroon, Mura) is Muslim, so their romance plays out in secret — and simply finding somewhere to be intimate is a constant mission. Maharashtrian Parvaty faces moving back to her Ratnagiri village due to Mumbai's changing skyline, with her chawl earmarked for demolition in favour of a high-rise, and her rights to her home given little consideration.

For spending time with Prabha, Anu and Parvaty in this character- and mood-driven rather than story-driven gem — for juxtaposing the perceptions and the truths about their existences, too, and of women who head to Mumbai to forge their careers in general — Kapadia cemented herself as one of 2024's cinematic revelations. Awards and nominations have kept following. When it received Cannes' second-most prestigious annual prize after the Palme d'Or, so coming in behind Anora, it did so after becoming the first Indian film in 30 years to play in the renowned festival's official competition. From there, All We Imagine as Light earned two Golden Globe nods, with its guiding force a Best Director nominee. Oscar buzz lingers, even if the film wasn't selected by India as its submission for the Best International Feature category. Another tick of approval, among many, came when Kapadia's picture was named as one of Barack Obama's ten favourite movies for 2024.

Is this response all that the writer/director dared to imagine when All We Imagine as Light first sprang to mind as a student project? "No, of course not," Kapadia tells Concrete Playground. "I took some time to raise the funding for this film. It was raised using a lot of funds from public institutions all over Europe, so it was a long process that they have there, and you just want to be able to make the film. That's your main priority. So we were just slowly, slowly building the budget to be able to shoot it. For us, everything has come as such a bonus — the making of the film itself was such a great, great thing for us that we, at points, would think 'are we going to be able to do it?'. Because it really takes time and that's fine. I appreciate the process. But you don't really think of what will happen. You hope, of course, that it'll do well and people will see it. But this was quite unexpected, I have to say."

"I'm really so grateful," Kapadia also advises, while recognising that the fact that she's still just one of two women contending for the Best Director Golden Globe at 2025's ceremony — alongside The Substance's Coralie Fargeat — should be a relic of the past, as should cinema's poor history of appreciating female filmmakers. "And it's not just about women and a gender thing, but representation in all ways. There is diversity that needs to be there in representation, which is people of all races and castes and class. If selection committees were more diverse, I think this problem would not exist," Kapadia notes.

All We Imagine as Light isn't just helping to push diversity in filmmaking accolades to the fore, but also the diversity of Indian cinema with audiences outside of the country itself. "I think in India, we have a very self-sustained ecosystem of cinema." Kapadia says. "I think that the West needs to start looking more at Indian cinema and accepting that there are different ways. There are different ways of acting. There are different ways of performance. We come from a very theatrical, sometimes melodramatic background, and that is also a way. So I think that the diversity of Indian cinema is not restricted to Bollywood. There is Tamil cinema, which is absolutely incredible; Malayalam cinema, which is really doing very avant-garde stuff; and, of course, Telugu cinema has now travelled with RRR and things like this."

What did it mean for All We Imagine as Light to break a three-decade drought for Indian films in Cannes' competition? How did the film evolve from an idea for a graduation film? Kapadia also chatted with us both — as well as what influenced the movie's narrative elements, and inspires the filmmaker in general; the many layers to the script, and how to balance what is told visually versus what's conveyed in dialogue; how the writer/director's non-fiction filmmaking background had an imprint; bringing a different vision of Mumbai to the screen; and more.

On All We Imagine as Light Being the First Indian Film to Play in Competition at Cannes in 30 Years

"I think it was really great that we were in competition. It's also a bit scary, because it's your first fiction movie and it's competing with all these big directors who you've admired and who you studied at film school. So you're a bit nervous, like 'oh my god, what is it going to be?'. So I think for for me it was a lot of nerves, and I was a bit like 'will I be, will it …', about standing up to all these expectations of this thing about 30 years.

But the truth is that in India, we do have — like this year, there was an Indian film in every section in Cannes. And that's really great because I think that having not having a film in 30 years is a bit of a disappointment for us as Indian filmmakers. I think that Indian films have been doing really well in other festivals. And a lot of competitions, in Venice and Locarno, there's more or less always an Indian film.

So I think this 30-year pressure was a bit overdue, in that it should have had more Indian films. But yeah, I was nervous that I hoped that the film would be accepted and wouldn't feel like it was not worthy of being there."

On the Movie's Evolution From Student Project to Earning Global Attention and Accolades

"I had to make my what we call a diploma film at the Film and Television Institute of India. I had a very two-page thing about two two women who are friends, roommates, but have two different ideas of morality, and this was the starting point. But it was a very short 20-minute thing. And I had already thought that they should be nurses. So I was spending a lot of time trying to do more research about nursing. That's when I realised that I couldn't have done this in 20 minutes. I knew nothing. I needed more time to to think about all these things, to really explore this subject. I felt that 20 minutes was not enough. So I put it aside.

But at that time I already got in touch with Kani Kusruti, to play the younger nurse at that time because it was eight years ago. And then I stopped the project and I did something else for my diploma. And I had put it aside for some time, and then I thought I should get back to it.

A few years later, I got back to it and I started doing more research, meeting more people, spending a lot more time working on the details of the script. I was also making another movie at the same time, A Night of Knowing Nothing. So it was an on-off thing that I was doing, coming back to this film from time to time. And as I met more people, I got more stories that made it into the film, with all the interviews that I did and all of the young women I spoke to — and some part of myself, growing older also, because I went from being from the younger nurses age to the older nurse's age in the span of all this time. And I think that as you grow older, your perception of things also changes, of course. So my gaze also began to change a bit. And finally, this is the film that you see."

On Where the Movie's Main Narrative Elements Sprang From, Including Focusing on Three Women Across Generations, Classes and Languages

"I was thinking a lot about this question of friendship, and how certain friendships are very big city-driven. These people probably couldn't or wouldn't have met, or wouldn't have been friends, if it wasn't for Mumbai. For example, when you live in a city like Mumbai, you have to have a roommate — because it's really expensive, and sometimes you just have the roommate because you need to fill up the slot of the bed next to you because you need somebody to pay half the rent. So that's an odd kind of relationship, because you might not get along with this person. You don't want to be their friend. But now you're stuck with them for the 11-month lease. So that's a unique friendship.

So Prabha's Anu's boss, in a way. She's the head nurse. But now she's stuck with this girl who is very different from her — and they are age-wise also different from each other, and their perspectives to life are very different. I was interested in this juxtaposition of two people who are so different in their way of thinking, but have to share a room, and what could come out of this relationship.

And even Parvaty, who works with Prabha now, she's Maharashtrian and she speaks a different language. And they would not have met if it wasn't for Mumbai, because she would never have gone to Kerala. And there's nowhere else that Prabha would have probably gone. So that friendship is also unique because, again, it's a very Mumbai friendship between a Maharashtrian woman and a Malayali nurse.

So I wanted to kind of have these unique friendships, which are, for me, very Mumbai friendships, in the film. And the character of Parvaty wasn't really that important when I started writing the film, but as I began to do more research into the housing situation — which for me was something that I had seen, but I hadn't delved into in a big way — I felt that it was something that I had to really address in the film."

On Layering the Impact of Societal Expectations, Cultural Clashes and Gentrification Upon the Film's Characters Into the Script

"It was quite a balancing act, because if you have three different trajectories, it's always a bit difficult to balance. And what we shot was a lot more than than you see in the film, of course. But I think we had a good editor, and along with him, we were finding that balance between the three stories and how they reflect on each other. How Parvaty doesn't feel lonely, even if she doesn't have a family — she doesn't want to go live with her son. While Prabha is somebody who's been so obsessed with the idea of a family, of a husband, and how that reflects on her — and how Prabha sees how free Anu is. And Anu is just a young girl, and she just wants to have sex with her boyfriend. It's a very fundamental thing. And the city doesn't really allow that.

So I was thinking of it that it's not individual stories, but how they reflect on each other and what they gain from each other's interactions with them. It was a difficult thing — and I also feel sometimes that I could have had a longer film, but my producer was like 'two hours is good enough'."

On Drawing Upon Kapadia's Background in Non-Fiction Filmmaking

"The way that we shot the film has a lot of non-fiction process to it. When I was writing the script, my same cinematographer shot my previous movie also, which was the documentary. So while I was writing the script, we would go out into the city and we would both shoot. Then we would come back and we would analyse what we chose to shoot, as if we were making a documentary — because in a documentary you can shoot a lot, and then you can come back and edit it, but in fiction, everything is fixed.

So we have to understand how we want to look. So we did a lot of tests of how our gaze should be towards the city. How do we feel about the lensing, and the camera movement, the feeling of space? So we thought a lot about these things, and that came from documentary, because we were shooting like documentary in our research.

And we also, I spoke to a lot of people at this time, like 100, 200 people, at least. Some people, I thought I will cast them in the film, so I would call them for screen tests, but then that ended up just being long conversations and no possibility of acting, but just conversations in the afternoons. So I wanted to keep some sense of that in the film, those interactions somehow, to keep them as well.

So we came up with this thing of putting a small, short documentary-like footage in the beginning and in the middle of the film — and giving it a sort of sense of a city symphony. And just talk about how diverse Mumbai really is. It's a city that is made by people who come from outside. There was nothing there. It was a bunch of islands. Only the Koli people lived there, and the British came and they reclaimed the land, and invited people to come to live and work there to create a new port.

So the fundamental idea of this city is that it's made up of people who are not from there, and I wanted to highlight that somehow."

On What Was Most Crucial for Kapadia to Convey About the City That She Was Born in, Then Came Back to as an Adult After Going to School Elsewhere

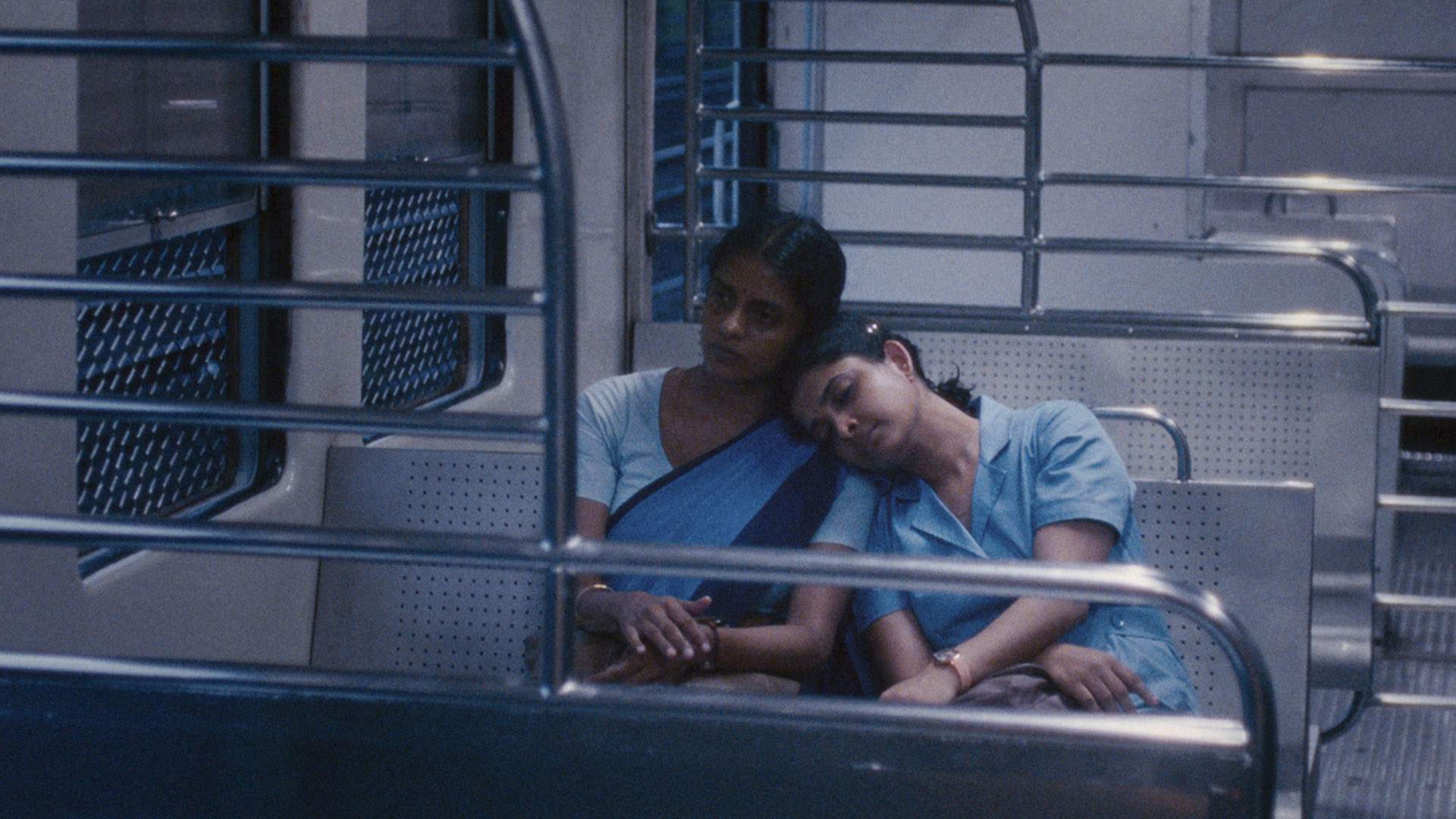

"The multilingual quality of the city. And also one of the things that is very important to me was the trains. Because it's what you end up seeing the most, because you spend a lot of time in the transport. And they become a space for a lot of different interactions — or relationships of the ladies compartment, where you make friends. You see the same people, you don't know them but you always nod because you know you'll see them tomorrow. And you try to think about their life outside of that compartment. But for those two hours, you are in that journey together. And all these things, I think a lot about. Maybe I'm too romantic about it, but I don't know, it's how I feel.

Also this question of gentrification was important to me, and the right to people owning property, and who has this right. I feel I could have made another whole film about it, because it's so complicated and there is so much anger that one feels towards this situation.

I wanted to also in a visual way talk about that. So you always see the buildings and then also the smaller houses and the slum area all together in a frame, and I wanted to give a visual sense of what the city is."

On Knowing What to Convey Visually and Where to Let Dialogue Tell the Story

"This is a real struggle. It's something that, as a filmmaker, you think about a lot because you don't have the visuals exactly on paper. You can't exactly say what they will be. And you have to rely a bit on the writing of the visuals and of the dialogue for the person who's giving you the grant to be able to understand it.

But for me, I can put an image of the city and I know what I'm thinking. So this is a big, big issue for me, about finding that balance.

And finally, when I'm editing, it's when I actually realise the balance and I can let go of a lot of information — which is being, I hope, conveyed visually and it doesn't need to be told in lines. But its a big balancing act and I hope to get better and better at it because sometimes I feel — it's complicated, I have a complicated relationship with this."

On the Guidance That Kapadia Gave Her Cast When They're Tasked with Revealing Complicated Characters Via Actions and Expressions as Much, If Not More, Than Dialogue

"We we did a lot of rehearsals before shooting. For three weeks, we we all stayed together. We did it like a theatre workshop. So we worked on each of the characters' body language, on how silences are — and we did a really fun exercise, which was that we did many scenes where the actors would play the characters, but between dialogues say what the character is thinking.

So if there was silence, you would hear what Anu's mind is going on, thinking to herself about — let's say how she's planning something or how she's bored or whatever. So we would do these exercises where the thoughts were all spoken out, so we all know how to think about it. And the actors are really, really great, and they brought in a lot of their own thoughts about this, and I think it was way beyond what I had even thought. It was really collaborative and rich process for me."

On What Inspires Kapadia as a Filmmaker

"Everything inspires me. I think that that's the privilege of being a filmmaker, that life seems more interesting than cinema, and I want to make films about everything all the time. It's crazy.

I feel, I think just being in the world and seeing the world around you, really everything is so inspiring. And for me, my films are also about very daily things, so that is why daily life for me is is my inspiration."

On the Importance of Conveying Prabha, Anu and Parvaty's Ongoing Fights for Agency

"It was really what you're saying, that it is these tentacles of this patriarchal society that still hold you down, and in spite of being financially independent and physically away from the family, it is something that is for me, certainly, a real pity. It's a matter of genuine anger. Because I've seen it in people in my family as well, and girlfriends around me, and it's something that always just makes me very frustrated.

So I wanted to bring out that frustration in the film and say that at least if this society is failing us in so many ways, if we could find some utopian-like space where we could all connect, at least in a way that is beyond our immediate identity and beyond our immediate morality, to at least be supportive of one another — it's a small move, but it's, for me, a big one."

On How the Film's Sometimes-Romantic, Sometimes-Clinical Aesthetic Adopts Its Characters' Different Gazes

"I wanted to shoot the film from the gaze of the characters. So for Anu, whenever we see her and Shiaz, the city seems very nice. They're walking through the Mohammed Ali Road and eating kebabs and the beautiful lights, and the smoke coming out. Because I think cities are better when you are with a friend or when you are with a lover. If you are in that mood, then somehow things look better. They might not be, but it's how it is. You don't mind sitting in a really crowded public bus — you don't mind that there is traffic because it means you'll have a little bit more time together. And these very normal things that would annoy you suddenly become okay.

So I wanted to have that kind subjectivity to the film, whenever we are with Anu and Shiaz, then we also feel delighted at everything. And if you see the city through the wet droplets, that all looks so.

Then with Prabha, it's more about the daily grind. She's not going to look at how beautiful it is, but just go from one place to the other, and it's a functional look.

And for Parvaty, there is a sense of this complete injustice, feeling that she's going to be thrown out of a place that she's been calling home for 22 years.

So I was trying in some senses to have a different gaze to the city, because I think it is all these things. It is a place of freedom for a lot of young women. It is a place of anonymity and that anonymity gives freedom. But it's also a harsh reality and a difficult city. So I was hoping that through these different gazes these layers came out."

All We Imagine as Light opened in cinemas Down Under on Thursday, December 26, 2024.