The Bluffer’s Guide to Sake

Masu's sommelier takes us through the basics.

Sake's been wearing its 'Big in Japan' t-shirt for almost 2000 years, yet it's only in recent years that its global popularity has exploded: sales shot up 99% from 2001 to 2011 and everyone seems to know what it is now, even your philistine flatmate who only ingests microwaveable food and Woodstock.

Commonly known as rice wine (a misnomer, considering the fermentation process is more akin to beer), sake is indeed made from rice, in addition to water, yeast, and a mold known as Koji-kin. It's the only drink in the world said to have umami - the elusive fifth basic taste that translates as "pleasantly savoury" (foods rich in umami include ripe tomatoes, mushrooms, soy sauce, and, oddly enough, breast milk).

Because Japanese culture is a study in contradictions and known for its ambiguity, there are no hard and fast rules when it comes to sake: it's not as simple as matching red wine with red meat; white wine with poultry and fish. And there are plenty of nuanced traditions and ceremonies associated with its serving and consumption. So here to give us a crash course is Meg Abbott-Walker, sake sommelier at Nic Watt's Masu. Located on Federal Street, the beautiful Masu (named after the cedar wood boxes sake is often served in) has one of the most extensive sake lists in Auckland and is the exclusive New Zealand stockist of several premium varieties.

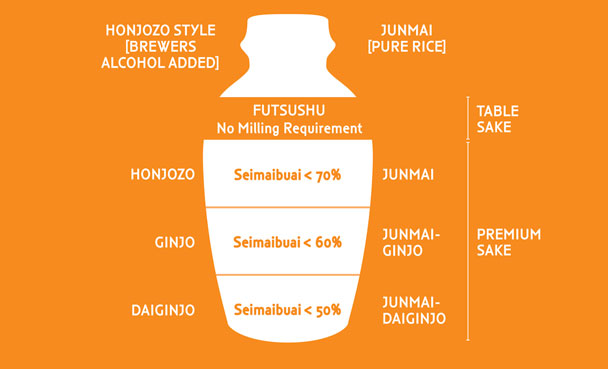

TYPES OF SAKE

Sake can be broadly classified into five categories based on the production process. The most premium are made from rice that's been very refined, or had its outer harder layers stripped away. Daiginjo-shu is the highest quality, with the rice grains polished to 50% of their original size. Ginjo-shu is generally sweeter and more delicate, with grains polished to 60% of their original size. Junmai-shu is bold and a bit acidic. Then you have Honjozo-shu and Futsuu-shu, which have decent amounts of brewer's alcohol added during production and rice that is less than 70% polished. Cheaper sakes are often served hot, while more premium varieties are drunk cold or at room temperature to preserve their flavour and aroma.

MAKING SAKE

Outside Japan there are only a couple of companies in the US and Australia making sake. It's difficult and expensive to produce on anything other than a large scale; you can't just whip it up on-site. One of the things sake brewers go on about a lot is the importance of their Koji room - Koji is rice that's been inoculated with a specific kind of mold, making it soft and fluffy like the rind of a wheel of camembert. Koji requires specialist equipment and expertise to make properly.

FOOD MATCHING

Just like wine, sake can be dry or sweet or varying levels of acidic, served at different temperatures and the flavours are incredibly broad: you can go from tropical to vegetable notes like cucumber to something really earthy and yeasty. There's no strict rules, but sake goes really well with other umami flavours and and can match a wide range of foods from gentle, subtle dishes through to strong red meats, really spicy food or rich sauces dependent on the flavour profile of each individual sake. Daijingo is great as an aperitif (a pre-meal drink) or, as it's quite delicate, with sashimi. Ginjo sakes can be sweeter or drier in style and are frequently very fragrant and floral - the sweeter styles can be great with fresh seafood such as crayfish. Sake doesn’t have as high levels of acidity as wine does, so when matching with oilier foods, like salmon or tempura, choosing a sake with higher acidity than the rest can be useful as a great palate cleanser. Junmai (pure rice) sakes as well as unpasteurized “nama” sakes will mostly fit the bill here.

ALCOHOL CONTENT

Sake's more alcoholic than wine and beer but less so than spirits; it sits at between 15-20%. There are some sparkling varieties that can be as low as 5%.

ETIQUETTE

It's quite simple for the drinker, at least - just make sure you let someone else pour it for you, sip instead of gulping, and, unless you want your host to constantly refill your cup, place you hand over it to show you've had enough.

BUYING SAKE IN STORES

Glengarry sells a couple of varieties and Tokyo Liquor has a pretty good range. It's kind of difficult as a lot of the labels are in Japanese, so it's best if you've got somebody to ask. But always look for SMV, which stands for sake metre value. It tells you the sweetness or dryness. While +2 is neutral, anything higher than that is dry and anything lower is sweeter. It can go down to minus 80 or minus 100. There will always be two other sets of numbers in English - an alcohol percentage presented as a range and a percentage telling you how much of the rice grain is remaining. The smaller this percentage, the higher grade the sake and the more expensive the bottle.

WHERE TO LEARN MORE

Wikipedia! Or at Masu. Masu hosts etiquette experiences for $35 per person (as an upgrade for those booking the private Obi Room), where the social and cultural contexts of producing, serving and drinking sake are discussed. It's great for sake fans or even those interested in Japanese culture, and this includes a tasting flight of three different sakes.

Photo credit:

Feature Image, Types of Sake, Food Matching provided by Masu

Making Sake via Sake World

Buying Sake in Stores via Jason Halayko