Buzzing Through the Highs, Hopes and Heartbreaks of Caring for Hollywood's Hummingbirds: Sally Aitken Talks 'Every Little Thing'

After stepping through The Wiggles' story in her previous film, this Australian documentarian flew into a portrait of Terry Masear's work with her Los Angeles hotline for hummingbirds.

Ask writer/director Sally Aitken about more than a year spent celebrating her documentary about Los Angeles' hummingbirds — a movie that premiered at the 2024 Sundance Film Festival, also screened at SXSW in Austin and Hot Docs in Toronto, then made its way Sydney and Adelaide's film fests as well, and was nominated for an AACTA Award across that journey — and she answers with a sense of humour. "I was about to make a little joke about 'it's like a little hummingbird migrating everywhere'," she tells Concrete Playground. That's a parallel drawn with the utmost of affection, however, as anyone that has seen Every Little Thing and witnessed the immense care that it has for the gorgeous tiny birds in front of its cameras will instantly recognise. "It's amazing," the Australian documentarian also notes about the film's global tour, flitting to Greece, Poland, New Zealand, the UK, the Netherlands, Estonia and Sweden, too, before it opened in Australian cinemas to kick off March 2025.

When Aitken turned her lens towards beloved Australian film critic David Stratton in 2017 doco David Stratton: A Cinematic Life, the end result played at Cannes. 2023's Hot Potato: The Story of The Wiggles, the movie immediately prior to Every Little Thing on her resume, screened at the first-ever SXSW Sydney. The last time that the filmmaker peered at nature on the big screen, in 2021's Valerie Taylor: Playing with Sharks, she also scored a Sundance premiere. Together, those four titles paint a picture not just of an Aussie director's success and recognition around the world, or of her versatility, but of her desire to dig into an array of different stories of our humanity. "I like to make films that look at this incredible world through a new lens or through the other end of the telescope," she advises about a recent resume that's spanned appreciating cinema, reappraising ocean predators, the origins of iconic childhood entertainers and now a hotline for hummingbirds.

Every Little Thing is indeed about hummingbirds in LA, but it's also about a person who has dedicated decades to tending to the birds' injuries. It was Terry Masear's book Fastest Things on Wings: Rescuing Hummingbirds in Hollywood — a review of it, to begin with — about her Los Angeles Hummingbird Rescue that sparked Aitken's second film of the 2020s about women and their connection with animals. That text was a memoir of its author's endeavours since 2004, but Every Little Thing's personal aspects, stepping through Masear's experiences beyond rehabilitating the smallest mature birds there are as well, is exclusive to the documentary. In interweaving the two, Aitken has crafted a pivotal chronicle of resilience among winged critters and humans alike. Wildlife rescue is a field of highs, hopes, healing and heartbreaks, as the film captures in detail. Existence is for all creatures anyway, great and small, as the documentary also examines.

A phone call for Masear, a retired UCLA professor, usually means that a hummingbird in the City of Angels is in trouble. The reality of human life in the Californian city isn't always kind to the American-native species, but Masear unceasingly is. Every Little Thing flutters through her efforts as birds after birds are brought to her door — and as she attends to them in their various stages of need, aiming to get each one back flying over LA in the wild. Cactus, Jimmy, Wasabi, Alexa, Mikhail: they're just some of the hummingbirds that flap in and out, and that Masear treats with the sincerest of compassion.

Jacquie Manning

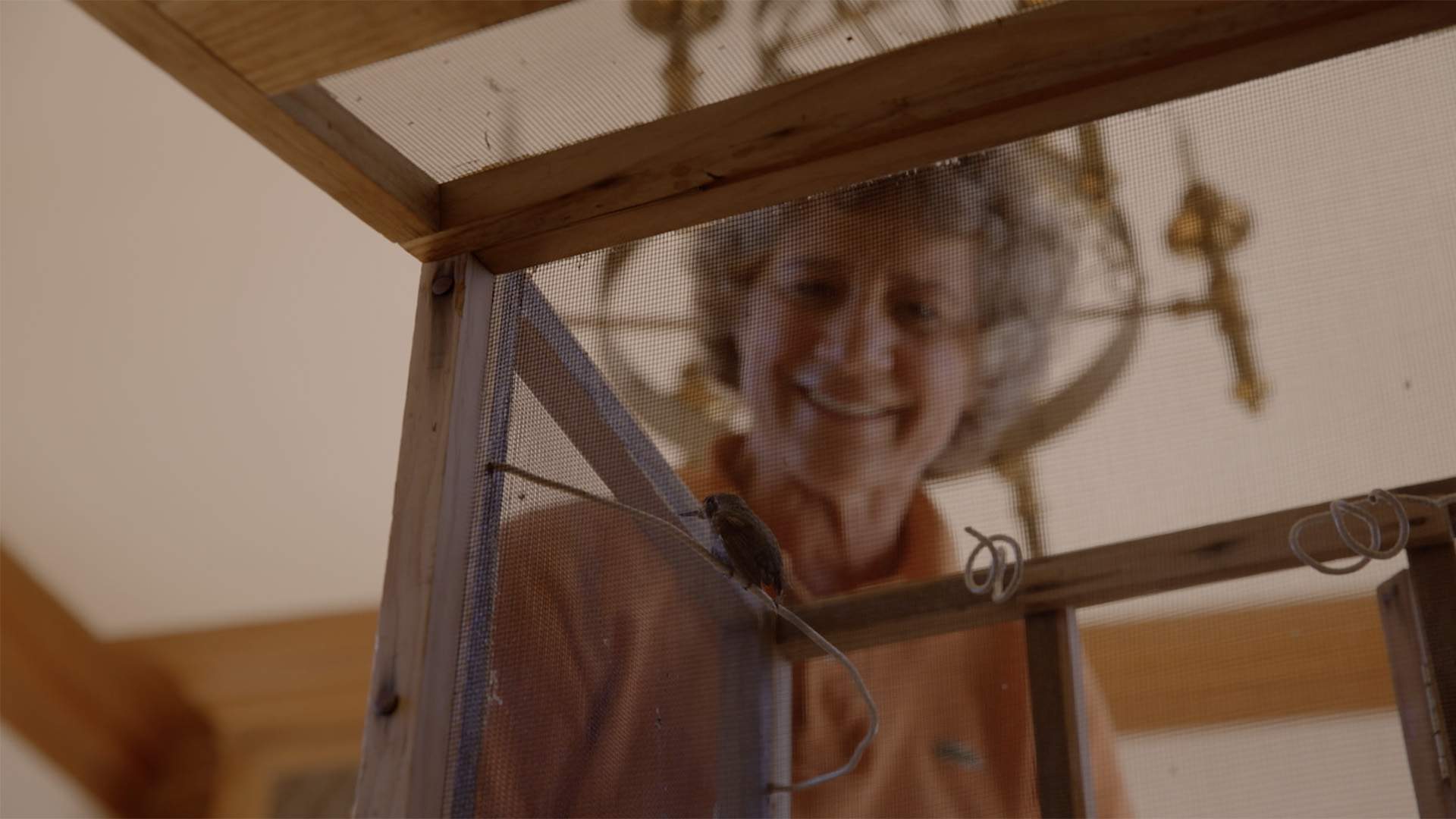

Every Little Thing surveys the ins and outs of the rehab process, including syringe-feeding fruit flies to babies as dawn breaks, taking birds through workouts to test their flying capacity, and transitioning them from incubators to aviaries and ideally back into the sunny skies. It explores the characters, feathered and human — and among the former, it is also well-aware that some under Masear's supervision won't make it. This deeply empathetic film sees the hummingbirds in all of their glory, using cameras capable of capturing their super-fast speed, and also peers at Hollywood as they do thanks to bird's-eye view imagery. Crucially, it's as much about what it means to devote your time to another creature, to commit to riding the rollercoaster of their wins and setbacks, and to truly care.

After watching Every Little Thing, no one should look at feathered friends above, or at any animal life, in the same way again — and while viewing it, everyone should enjoy witnessing its critters in detail that they've likely never seen before. This is a touching movie, for audiences, those in it and the folks behind it. We also chatted with Aitken about the kindness at the picture's core, the inspiration to bring Masear's work to the screen, the film's personal turns, the extensive editing process thanks to hundreds of hours of footage, its often-breathtaking visual approach, and weathering the act that bird rehab involves both soaring joy and aching sorrow.

On Every Little Thing's Year-Plus-Long Journey From Premiering at Sundance to Releasing in Australian Cinemas, Via Playing at Other Film Festivals Around the World — and the Reaction to It

"It's so incredible as a filmmaker when you can see, very visibly in these kinds of scenarios like film festivals and in front of cinema audiences, how people are affected by the film. And I don't mean you perversely sitting there waiting for people to clap, or to cry or whatever, but the fact that the film is an emotional film for people.

I think that's the affirming part of it, because we set out to make something that would be an invitation and something that would be a work that wasn't necessarily literal — that invited people to these ideas of compassion and kindness in a very beautiful way, with the sunny cinematography and the delicate hummingbirds — and that was supposed to also be about us as much as the birds.

To have a film that premieres at Sundance is a thrill. To then be consecutively invited to all of these incredibly prestigious marquee film festivals, and then now to be in a cinema run, that's extraordinary — especially, especially right now, in the marketplace right now, where most of the offer is murdered bodies and people in office doing pretty crazy things. So, yeah, it's lovely."

On What It Means as an Australian Filmmaker to Have Your Work Repeatedly Embraced by Festivals Across the Globe, as Aitken's David Stratton, Valerie Taylor, The Wiggles and Now Terry Masear Docos Have Enjoyed

"It's funny because all those films are really quite different, but maybe they're also helmed by something that you're not even conscious that you're necessarily reaching for when you're making the film.

I am very interested in our humanity. I like to make films that look at this incredible world through a new lens or through the other end of the telescope. So it's a thrill when that work gets invited to any of those festivals that you're mentioning. These are extraordinary environments to see work from all around the world.

And I think it just speaks to the fact that we have an industry in Australia that is pretty challenged right now, and we are making work that that is as good, on par, right up there with everybody else — and that feels really good to be part of this global independent filmmaking sector."

On Why Aitken Was Inspired to Bring Masear's Work with Hummingbirds to the Screen

"Initially, I was sent the review of Terry's memoir and I genuinely thought 'what the heck? A hotline for hummingbirds?'. 'That is really very particular' was my initial thought.

The curiosity of that was amazing to me. Not that I'm unaware that wildlife rescue happens, but I just never conceived that somebody would have such a singular focus — that hummingbirds would have this 24/7 helpline. And what on earth did that look like?

So it was very much initially a curiosity, and when I read Terry's book, I realised it was so much more than that. The way she writes about the birds, it's very metaphorical. I realised in that moment there was an incredible opportunity to see these birds not just in their cinematic beauty — obviously the visual appeal of this film was always there — but that they could be this carrier of these much bigger philosophical ideas, these universal truths about our humanity. They were like a mirror to us.

So I thought 'that is a really interesting film', that possibility, that invitation. It felt to me like this was much more than the story of someone just rehabilitating the hummingbirds that may be in that rehabilitation. It was actually a rehabilitation for ourselves. That was the starting point."

On Making Two Films in the Past Four Years About Women and Their Work with Animals, and Their Place Among Aitken's Diverse Filmography Otherwise

"It's certainly no secret that I am a huge champion of women's stories — women who are brilliant, women who are badass, women who are dastardly, women who are heroic. I think we can't scream those stories enough.

But actually, what was quite funny, especially at Sundance — because Valerie Taylor: Playing with Sharks played at Sundance, and then this just played three years later — so many of the moderators, exactly like you, observed, they say 'oh, Sally was here three years ago with this film about this woman and the natural world, and what draws you to these stories of women?'. And the truth is that I make films about all kinds of things. I do true crime. I do music. I do all sorts of stories.

So what I would say was 'well, fun fact, between Playing with Sharks and Every Little Thing, I made a small film about a small group called The Wiggles'. And actually the crowd, who are American by and large, they all cracked up laughing because it's so incongruous, right? This story about this childhood band in the midst of these films about ourselves and the interconnectedness with the natural, amazing, wonderful, miraculous world that we live in.

But I think it's the same thing as what we were talking about before: it's finding a story that you think you know and telling this totally different story about that thing. So whether that's about sharks and the demonisation of sharks, and actually seeing them through the eyes of a woman who's quite literally been playing with them since the 1950s; or whether that's seeing the most well-known yellow-, purple-, red-, blue-clad characters that we see every day or every week on our breakfast television, and suddenly seeing them not in those colours, but seeing them as an incredible, incredible story of chasing your dreams, and this audacious idea of school teachers making it to Madison Square Garden; or whether it's hummingbirds, which in America are ubiquitous, they're just in everybody's backyard, and actually seeing them as these kind of magical fairy creatures — it's that same idea.

It's just taking these things and putting a whole new lens on them, and telling a really hopefully cinematic, emotional story in the process."

On How Every Little Thing Also Became About Masear's Personal Story

"So it is really an act of faith, making a documentary. She says in the film she doesn't trust easily. That is true. What is also true is that when I read her book, her book doesn't talk about her personal story at all. Her book very much deals with the hummingbirds that she has looked after in the last 20-odd years, and it takes a few of those very memorable hummingbirds and explores the stories of how she came to care for those birds and what happened to those birds through rehab. That's essentially what the book is talking about.

So the book is very much about her and the work with the rehabilitation. But it's this funny thing when you're making a film, especially a film that is observational — and documentaries on that kind of film, you're a very small crew. You're very, very tight. You're very intimate. And you're all signed up to this unknown adventure, because it's not like a drama.

I always joke, I always think this is so much harder because we don't have a script, you don't have paid actors, you're not able to write your way out of the scene. You're actually filming real life.

But she became increasingly comfortable. I'm very transparent in the way that I work. I like to tell people what my intention is, and also share my own vulnerabilities. I don't know how it's going to work out. Certainly that's not a statement that's not confident, but it's saying 'we're all in this together' — and I think that's very disarming for people, and certainly for Terry. She felt like she was among people who really valued her work, and so of course she started to trust us.

And then so what actually happened is that she started opening up about her personal life — and of course, as soon as she did that, that was amazing, because so much fell into place in relation to some of the motivations for why she does the work that she does, or what might inspire her to do this work in the first place.

So while that all happened, I also then, when I got into the edit with my brilliant, brilliant editor Tania Nehme [Monolith], I didn't want to make a film that was completely didactic. And so, like I said before, it was really an invitation. I wanted to draw this idea of Terry's biography, but to do it still in this lyrical, poetic way that just revealed the layers of her biography as we moved through the rehab process."

On the Challenges of Editing, Including the Difficulties of Whittling Down the Footage and Deciding Which Hummingbird Stories to Tell

"You are not wrong: the edit is absolutely the challenge, the moment that you go 'oh my god, I think I need to go and open a florist shop. Can I do it? It's really hard. How can these tiny birds be so goddamn heavy?'. You definitely have these moments where you think 'what?', and the volume of the footage was a big part of that.

Terry takes so many calls through the season, and of course we captured as much as we could, but it's really a process, an iterative process. And so we got into the edit suite, and the one clear thing that I remember discussing with Tania was that our task in the edit was really to make the smallest things feel giant, to feel epic, to feel the stuff of grand cinema. So with that aspiration in mind, it was really just a process of working and working our way through the volume of footage.

And then some of the characters, they reveal themselves to you. Jimmy is hilarious. Cactus is vulnerable. Alexa and Mikhail are thwarted love. In the mix of things, we wanted these characters to — in a way — be this mirror to the human experience as much as they were their own individual heroes, or are their own individual heroes, in the film."

On Capturing Stunning Footage of Birds Known for Their Super-Fast Speed, and Pairing It with a Bird's-Eye View of Los Angeles

"Right from the beginning, it felt like a film that had all of this visual potential. So if you've seen a hummingbird in real life, you know that they are incredibly fast — and magical. They look like fairies. They just whip in, they kind of come up and look at you, and then they whip off again.

But the way that Terry wrote about them was very metaphoric, like I was saying. So I wanted to reach for a visual style and a visual treatment that was really replicating the way that Terry sees the birds — and the way that she sees them is otherworldly.

So in the same way that a hotline for hummingbirds is quite specific, there is also a cinematographer whose specialty is hummingbirds. That's also pretty specific. So her name is Ann Johnson Prum [Terra Mater] and she lives in America. She is American. And she's an expert cinematographer with a camera called the Phantom Flex. The Phantom Flex is a camera that shoots at an incredibly high frame rate — it goes up to 1000 frames a second. And what that means is that when you film footage at a high frame rate, you can then really slow it down.

So from the beginning, we wanted to lean into this idea of being able to enter into the hummingbirds' realm and not just be in our human limited sensory experience of them. And the other thing is that we have also two other cinematographers in the camera team, two Australian DPs, Dan Freene [Skategoat] and Nathan Barlow [a Valerie Taylor: Playing with Sharks alum]. And so we leant into cinematic time lenses, and that gave us macro lenses. So that gave us an ability to be really close to the birds — so close, in fact, that at times you can see their eyelashes. I mean, who knew that hummingbirds have eyelashes?

So it was a huge challenge, but we really wanted to meet that challenge in order to make the birds feel worthy of this big-screen treatment, because they are worthy of a big-screen treatment. And it's really quite trippy, actually, when you know that a hummingbird is quite literally the size of your little finger, and then you're looking at it on a giant cinema screen — it's quite trippy, the experience for the viewers.

So I was quite interested in playing with all of those ideas."

On Every Little Thing's Crew Coping with the Casualties in Masear's Line of Work — as Newcomers to Facing It — But Ensuring That This Is a Film of Hope

"That's a really perceptive question. And we were talking before about that intimate relationship — absolutely, of course, every time you make a film about whatever subject, it changes you or it affects you, not only because you're learning new things, but because you're working with, encountering, engaging with, being trusted with other people's experiences and their stories. So I found the whole experience incredibly moving.

I think that, at the same time that I was in the edit — and Tania and I worked incredibly closely together. The shoot is very intense, you have the whole team, but when you're in the edit, it's really just the two of you. And the algorithms didn't make this film. It's a film that really, really does come from the heart, and it's exploring things that aren't always talked about or aren't always obvious.

So to circle back to your first question, which is about the reaction, it's hugely affirming when people respond to that because it tells you that that need is there in all of us to have these stories about what is good in our humanity, what is kind, what is empathetic in a world that's actually constantly cynical — and constantly telling you that people are bad and politics is awful, and the world is existentially threatened with climate change.

When you are in this news cycle, which is a horror show, when there's a story that comes along that reminds you that humans are resilient, imaginative, kind and empathetic, that's a good news story. And it's not like a Pollyanna good news — as you say, birds die. Life is tragic. Life is unfair. Life is awful. But the message, I suppose, in the film is that what matters is how you respond to that and the compassion that you put in when you're engaged in life.

And I just thought that was such an extraordinary idea, along with the idea that if you take the time to get on bended knee for something that is so small, that's a giant act of your own humanity. I just thought that was such a strong, compelling call to arms for all of us, for how we can be — we can just be better."

Every Little Thing opened in Australian cinemas on Thursday, March 6, 2025.