-

News

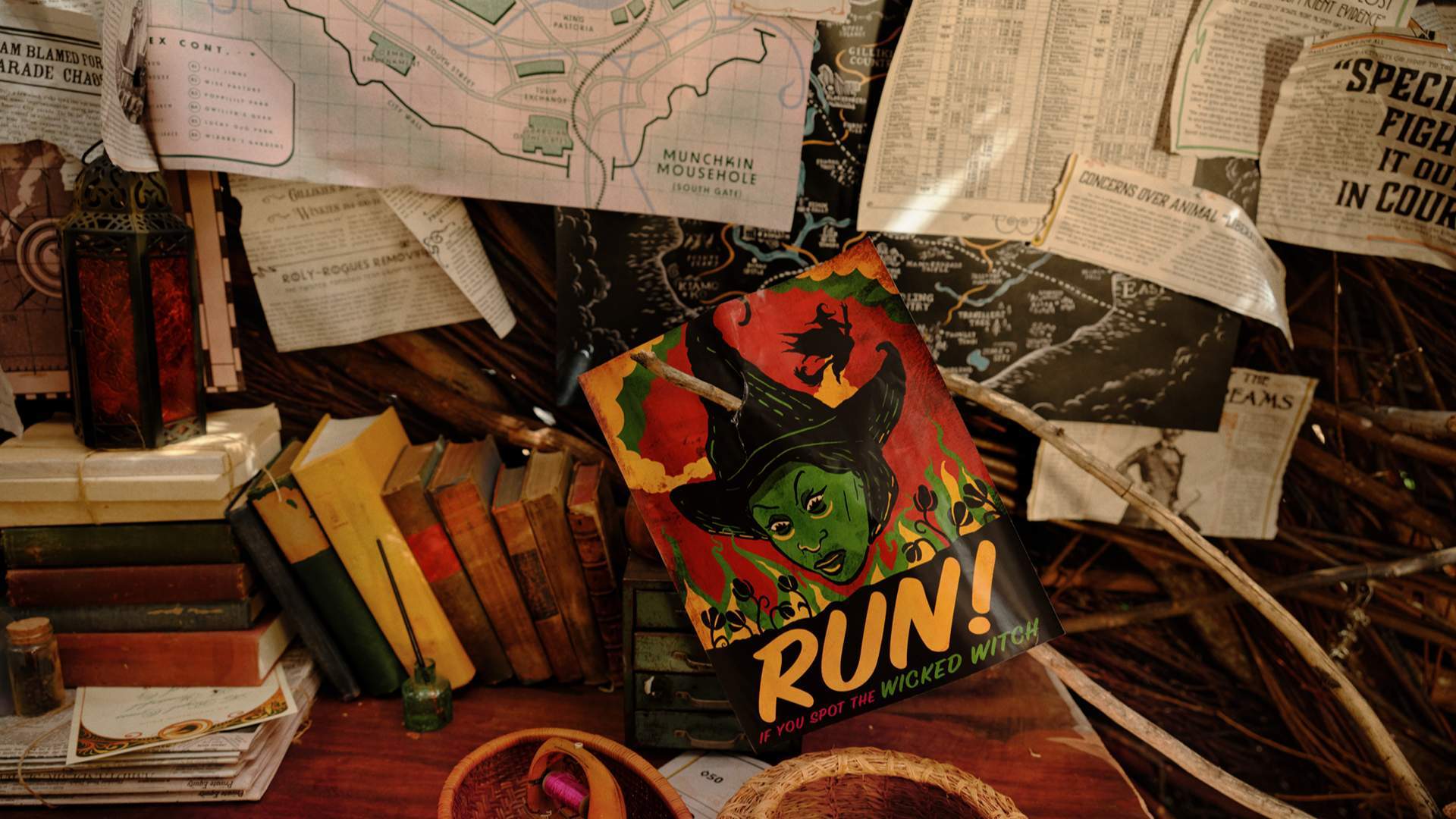

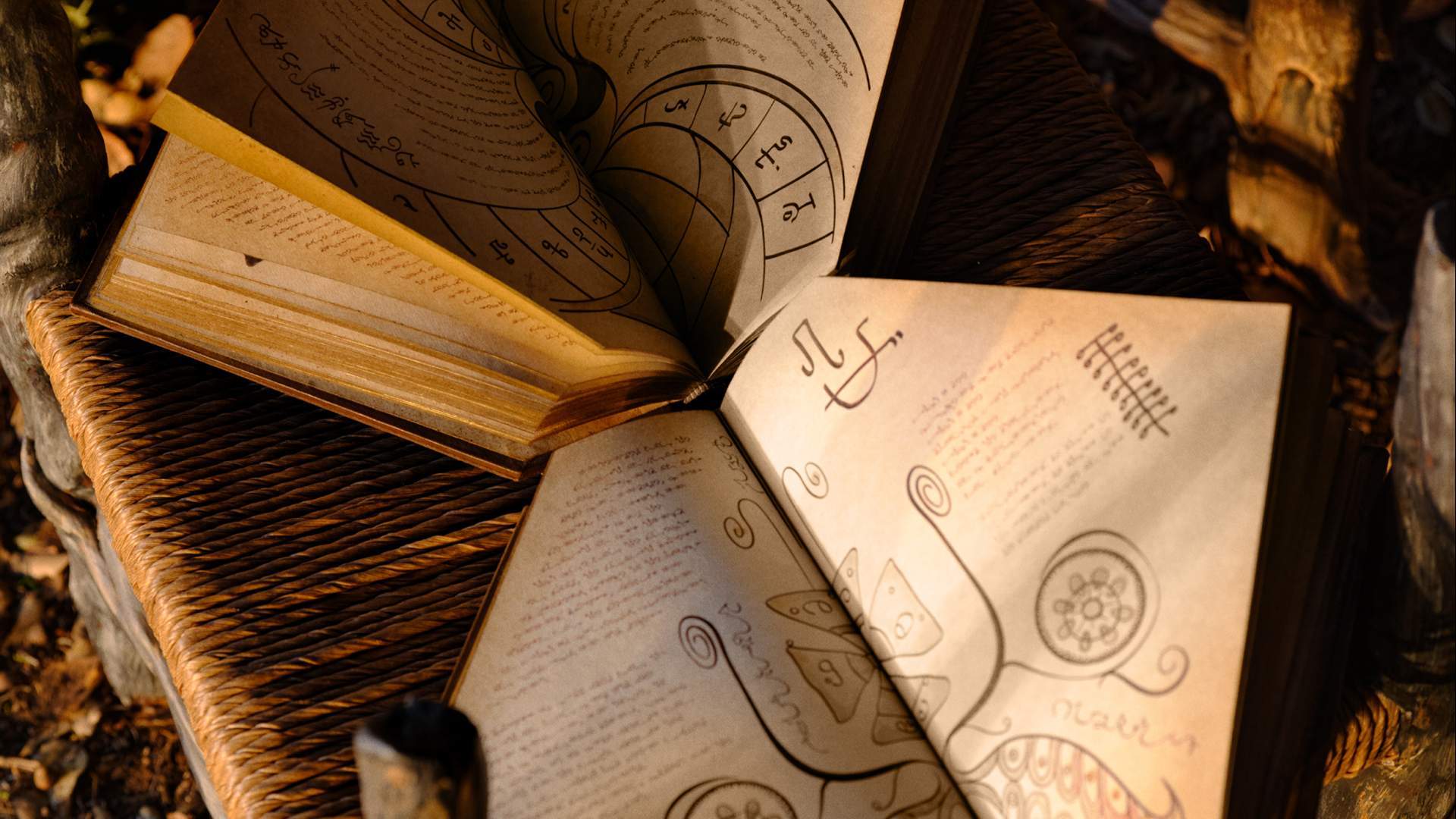

Spend an Evening in the Ozian Forest, as This Wicked Experience and Overnight Stay Features a Hollywood Hang with Cynthia Erivo

Hollywood star Cynthia Erivo is opening the doors to a magical forest hideaway, inviting fans to explore Oz up close through an immersive experience and overnight stay.

{"id":1043540,"type":"arts-entertainment","icon":"newspaper-clipping","info":"","name":"Spend an Evening in the Ozian Forest, as This Wicked Experience and Overnight Stay Features a Hollywood Hang with Cynthia Erivo","description":"Hollywood star Cynthia Erivo is opening the doors to a magical forest hideaway, inviting fans to explore Oz up close through an immersive experience and overnight stay.","thumbnail":"https:\/\/cdn.concreteplayground.com\/content\/uploads\/2025\/11\/WickedAirbnb_ElphabasRetreat-Campfire_Supplied-488x300.jpg","photo":"https:\/\/cdn.concreteplayground.com\/content\/uploads\/2025\/11\/WickedAirbnb_ElphabasRetreat-Campfire_Supplied.jpg","url":"https:\/\/concreteplayground.com\/darwin\/arts-entertainment\/elpabas-retreat-airbnb-los-angeles","latitude":"","longitude":"","address":"","booking":"","archive":{"title":"News","url":"https:\/\/concreteplayground.com\/darwin\/latest"},"banners":[{"src":"https:\/\/cdn.concreteplayground.com\/content\/uploads\/2025\/11\/WickedAirbnb_ElphabasRetreat-Campfire_Supplied.jpg","alt":"Spend an Evening in the Ozian Forest, as This Wicked Experience and Overnight Stay Features a Hollywood Hang with Cynthia Erivo"},{"src":"https:\/\/cdn.concreteplayground.com\/content\/uploads\/2025\/11\/WickedAirbnb_ElphabasRetreat-Hat_Supplied.jpg","alt":""},{"src":"https:\/\/cdn.concreteplayground.com\/content\/uploads\/2025\/11\/WickedAirbnb_ElphabasRetreat-Bed_Supplied.jpg","alt":""},{"src":"https:\/\/cdn.concreteplayground.com\/content\/uploads\/2025\/11\/WickedAirbnb_ElphabasRetreat-Exterior_Supplied.jpg","alt":""},{"src":"https:\/\/cdn.concreteplayground.com\/content\/uploads\/2025\/11\/WickedAirbnb_ElphabasRetreat-Glasses_Supplied.jpg","alt":""},{"src":"https:\/\/cdn.concreteplayground.com\/content\/uploads\/2025\/11\/WickedAirbnb_ElphabasRetreat-TeaFlorals_Supplied.jpg","alt":""},{"src":"https:\/\/cdn.concreteplayground.com\/content\/uploads\/2025\/11\/WickedAirbnb_ElphabasRetreat-Tea_Supplied.jpg","alt":""},{"src":"https:\/\/cdn.concreteplayground.com\/content\/uploads\/2025\/11\/WickedAirbnb_ElphabasRetreat-Posters_Supplied.jpg","alt":""},{"src":"https:\/\/cdn.concreteplayground.com\/content\/uploads\/2025\/11\/WickedAirbnb_ElphabasRetreat-Details_Supplied.jpg","alt":""},{"src":"https:\/\/cdn.concreteplayground.com\/content\/uploads\/2025\/11\/WickedAirbnb_ElphabasRetreat-Interior_Supplied.jpg","alt":""},{"src":"https:\/\/cdn.concreteplayground.com\/content\/uploads\/2025\/11\/WickedAirbnb_ElphabasRetreat-Grimmerie_Supplied.jpg","alt":""},{"src":"https:\/\/cdn.concreteplayground.com\/content\/uploads\/2025\/11\/WickedAirbnb_ElphabasRetreat-Chair_Supplied.jpg","alt":""},{"src":"https:\/\/cdn.concreteplayground.com\/content\/uploads\/2025\/11\/WickedAirbnb_ElphabasRetreat-Brooms_Supplied.jpg","alt":""},{"src":"https:\/\/cdn.concreteplayground.com\/content\/uploads\/2025\/11\/WickedAirbnb_ElphabasRetreat-Broom_Supplied.jpg","alt":""}]}