What to Expect at Sydney's New Chau Chak Wing Museum

Humanity is the thread that connects all objects of art, science and ancient history at the University of Sydney’s new free museum.

“It’s been quite some time since Sydney had a brand new museum,” says Craig Barker, Head of Public Engagement at the Chau Chak Wing Museum. Barker is showing Concrete Playground around the new four-level museum that sits between the University of Sydney’s famous sandstone buildings and the entrance from Victoria Park in Camperdown. “It’s a real statement of how the University wants to share everything we have with Sydney,” says Barker. “It’s a space for everybody.”

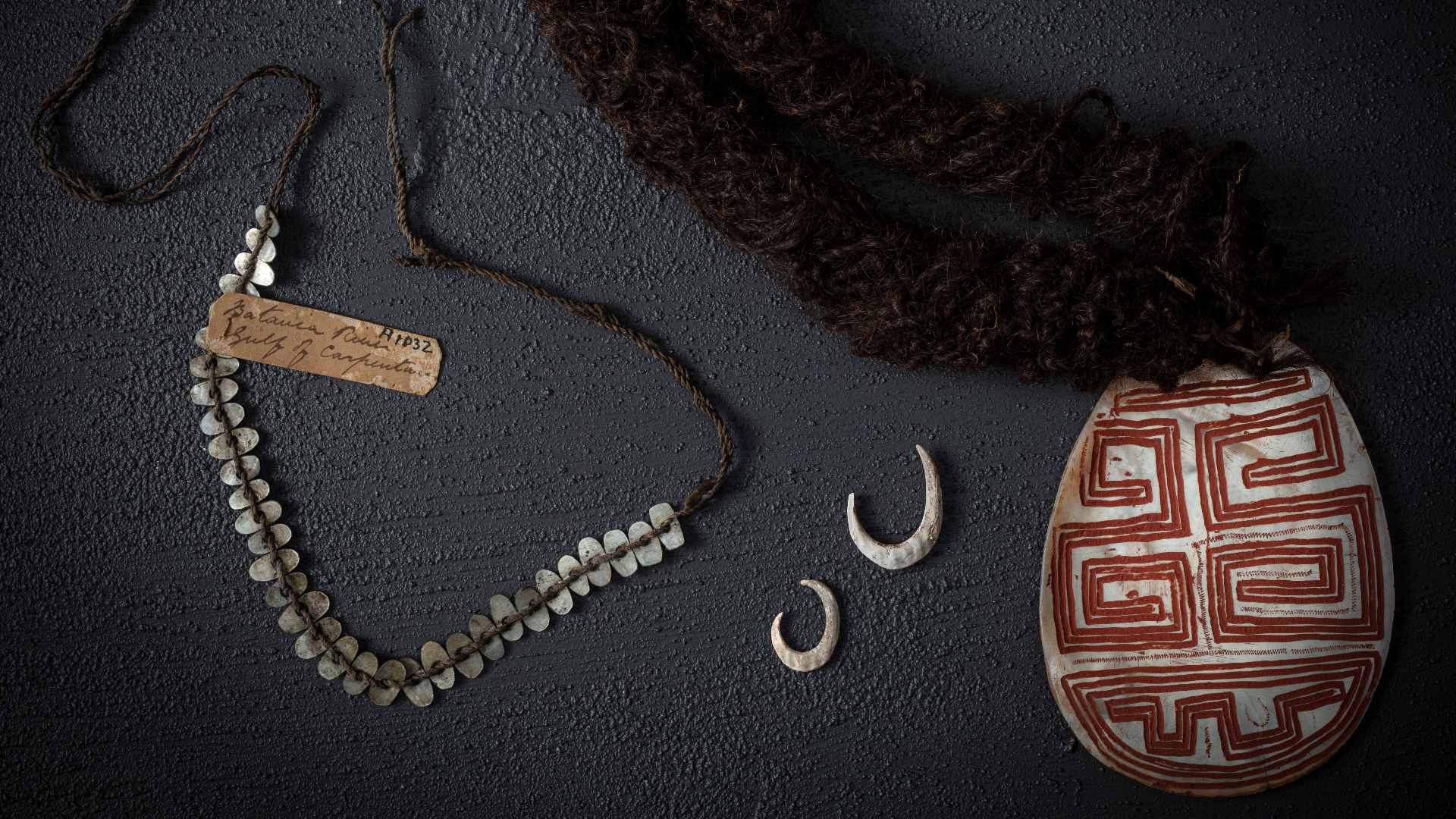

The Chau Chak Wing Museum brings together objects from three former museums owned by the University of Sydney: the Nicholson Museum of antiquities and archaeology, the Macleay Museum of natural history and cultural history and the University’s art collection.

“One of the very first comments we were getting was that it doesn’t fit; that there wasn’t any connection between antiquities from Ancient Greece, contemporary Aboriginal art, old Sydney photography and so on. And we wanted to prove that, actually, everything’s connected.”

The ARCHITECTURE

One of the first things you’ll notice about the Chau Chak Wing Museum is its shape. Designed like a floating box says Barker, “the museum appears to float like a cloud, and it links the historic centre of learning and the public.”

Named for Chinese Australian property developer Dr Chau Chak Wing, who gave $15 million to the University for this project, the space was designed by Sydney architectural firm Johnson Pilton Walker (JPW), which also worked on the National Portrait Gallery of Australia in Canberra and is working on the Sydney Modern Project.

Its cube-like exterior is somewhat of a trick of the eye; when you enter the museum it has seemingly endless space. It’s also cleverly filled with light, without causing any damage to the precious artefacts housed inside. Not only does it have four levels of gallery space, but also teaching rooms and public education spaces, which will eventually host talks and events with the University’s staff.

Art vs Science

There are a whopping 18 free exhibitions to explore across the whole museum. On the ground floor, you’ll find Object/Art/Specimens, which invites visitors to drawn their own connections between the various items on display.

The Earth of Sydney — a work by an environmental artist Alan Sonfist, created for the Sydney Biennale 1982 — is a series of soil impressions taken from different parts of the city, mounted in square plaques on the wall. “Basically, you have the entire Sydney landscape on one wall,” says Barker.

Then, positioned nearby is a portrait of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights activist Charlie Perkins, by Robert Campbell Jnr. “As a visitor, you might see connections of human impact on the land,” says Barker. “It’s also challenging notions of how we think about land and the environment.”

A theme that’s poked and prodded throughout each exhibition space is what is art versus what is science, and it’s evident in the way curators have chosen to display items from SILLIAC, the first supercomputer built in an Australian university, to a 4.5 billion-year-old meteorite. Or, in artist and former medical doctor John Wardell Power’s geometric paintings.

“It’s that connection between art and science, and that there is no divide.”

Charting our histories

Upstairs in the Ian Potter Gallery is a temporary exhibition honouring the decades-long tradition of the University’s connection with Yolŋu artists. In Gululu dhuwala djalkiri / Welcome to the Yolŋu foundations, 350 works by generations of artists cover diverse disciplines, including bark paintings and sculptures.

“It’s a collaborative exhibition,” says Barker. It was developed in consultation with three Yolŋu art centres. “We’re working with community Elders to determine the stories they want to tell and how they want it displayed and interpreted.”

Artworks come from more than 20 Yolŋu clan groups and 100 artists and “a lot of the artists are grandchildren of other artists in this same exhibition. Exhibitions like these are a small step towards reconciliation and understanding of our cultures,” he adds.

Looking back to move forward

Opening a new museum of old objects, aged artworks and even mummified humans comes with plenty of discourse around the role of museums in the 21st century. “Within museums internationally there is big debate around the rights and responsibilities of ownership and repatriation of human remains,” says Barker.

“Everyone who works with the mummies regards these as people. I say goodnight to them when I leave. The curator of the Nicholson Collection will talk to them as people. In ancient Egyptian beliefs, the concept was that if your name remained alive — if your name was spoken — you would remain alive in the afterlife.”

The four Egyptian mummies were welcomed to country by the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council as the oldest inhabitants of the museum. The Chau Chak Wing Museum has the largest collection of Egyptian antiquities in Australia, which you can see across The Mummy Room and Pharaonic Obsessions on the second level.

As technology has advanced in the last decade, it’s now possible to ‘unwrap’ the shrouds of one mummy, Horus, using scanning and 3D visualisation. It’s non-invasive and, scientifically, helps date Horus as a seven-year-old boy who lived in the first century AD.

“When I started teaching Horus to students in the late 90s, we thought that it was a girl because the death mask was feminine, so at some stage he was given the wrong death mask. It wasn’t until 2011 that we had sophisticated enough scanning that we could tell he was a male. Without us needing to touch the body in any way shape or form.”

Inverting the narrative

What’s evident at the Chau Chak Wing Museum is that you should come to expect the unexpected. In the ancient Mediterranean section, you’ll find a large-scale Lego model of Pompeii built by Ryan McNaught, the Brick Man. Look closely and you’ll see Pink Floyd playing a gig and professor Mary Beard making a TV documentary.

Over in Natural Selections: animal worlds, you’ll find the largest beetle on the planet, collected before 1778, and the skull of a cyclops horse. Around the corner, thousands of Victorian era photography taken in Sydney. And by the bathrooms, a retelling of Homer’s The Iliad in butterflies.

Possibly most surprising is the contemporary art space named for one of the museum’s benefactors, Penelope Seidler, called the Penelope Gallery. The museum will invite a contemporary artist to create a work for the space responding to the museum’s collection.

The inaugural project is Daniel Boyd’s ‘Pediment/Impediment’, which uses a plaster cast of the museum’s model of the Acropolis seen underneath pools of light. As Barker says, Boyd is inverting the narrative. “Instead of the more common historical narrative of the imposition of colonial European iconography over First Nations Australia, he’s reversed the narrative.”

“Because Boyd’s work is involved with decolonisation, it fits into the broader narrative of how museums deal with their legacies around the world. We’ve now got an opportunity to show and share, and we want people to bring their own voices to the objects and share what they know too.”

The Chau Chak Wing Museum is open from 10am–5pm Monday–Wednesday; 10am–9pm Thursday; and 12–4pm on weekends. The Museum will be closed from December 23–January 6. It will re-open on January 7, 2021.

All images: University of Sydney.