Is Melbourne Now the Exhibition to End All Exhibitions?

400 artists' work over 8,000 square metres. This is the kind of exhibition we need to be open forever.

Melbourne Now is impossibly large. Too large to talk about in any cohesive way, in fact. With the work of over 400 artists covering over 8,000 square metres of space over multiple levels of two major galleries and in some cases even the city's streets, me giving a review of Melbourne Now is like someone writing a travel guide of the entire European continent after having spent seven days on a Contiki tour.

That being said, some conclusions can definitely be drawn. Firstly, the exhibition is impressive. After being toted for months as the National Gallery of Victoria's most ambitious project to date, it's now clear they weren't bluffing. Corridor after corridor, gallery after gallery, the work just keeps coming. If you were to give each artwork the attention it deserves, you would be there for days, and if exhibitions were in any way comparable to restaurants, Melbourne Now would be an all-you-can-eat type of place — one of the classy ones.

However, as you roam around the large collection of works on show, you do have to readjust the expectations you may have for any regular exhibition. There is no real theme. There's no concept or message; no fortified aesthetic. The strength of the exhibition lies in the artworks' many differences. Each masterfully curated gallery space ushers in a new idea, a new vision. As a portrait of contemporary Melbourne, the collection is oblique and discordant. While you may think of these qualities in a negative way — what is the purpose of art for if not to achieve some sense of meaning — these words are in fact evidence of the idea being executed well. The NGV gets it right. We can't talk about contemporary art as a whole without acknowledging its many differences.

The Bold and the Beautiful

Everyone knows beauty can be found in odd places, but in such rapid-fire succession Melbourne Now really does reveal the full spectrum. Firstly, there are the conventional forms. With 40 fashion labels, shoemakers, jewellery practitioners and textile designers showing their wares, a portion of the ground floor at the Ian Potter Centre channels the best of our fashion festivals with work from both emerging and established artists. The photographic work on display is another highlight of the conventionally beautiful. Paul Knight explores intimacy and companionship through an affecting photographic series of couples in bed. David Rosetzky's video piece Half-brother hypnotically explores intimacy and confidence through dance and (oddly enough) paper. And on a grander scale, Ash Keating just transformed the outside wall of the NGV into a remarkable impressionistic canvas with the ingenious help of fire extinguishers loaded with paint.

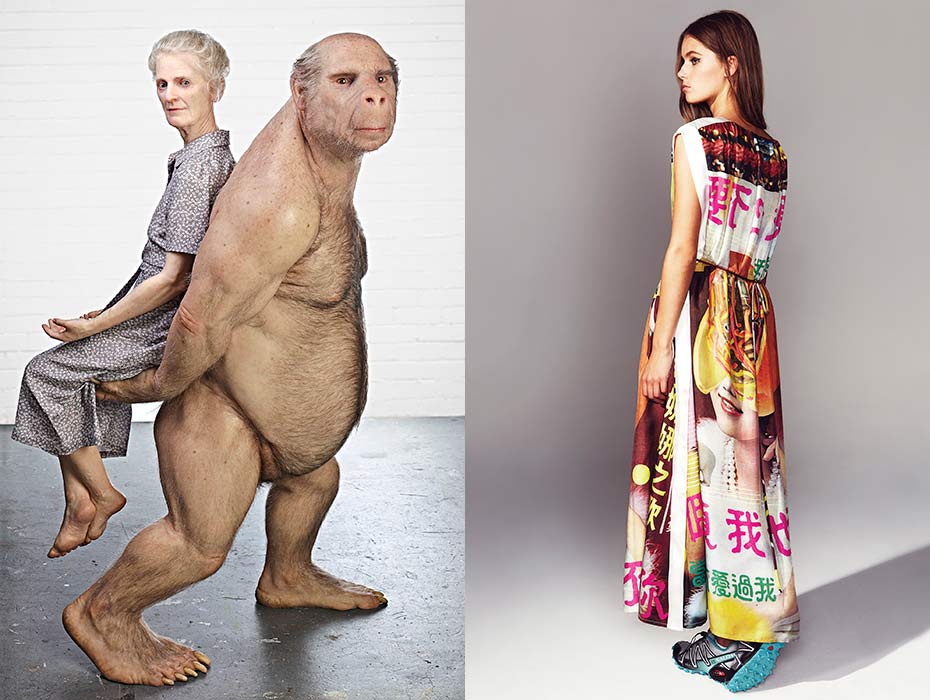

Then there's that other sphere — the dark and irresistible. Patricia Piccinini is well-known for her surreal and menacing depictions of altered beings, and The Carrier (pictured) is one of the best. Much like the work of Ron Mueck, it is a wonder to witness in the flesh (so to speak). Similarly, work from Stelarc's Ear on Arm series provides unhealthy intrigue, and Julia deVille creates a mysterious beauty in a room filled with jewel-encrusted dead animals.

The Silly and the Solemn

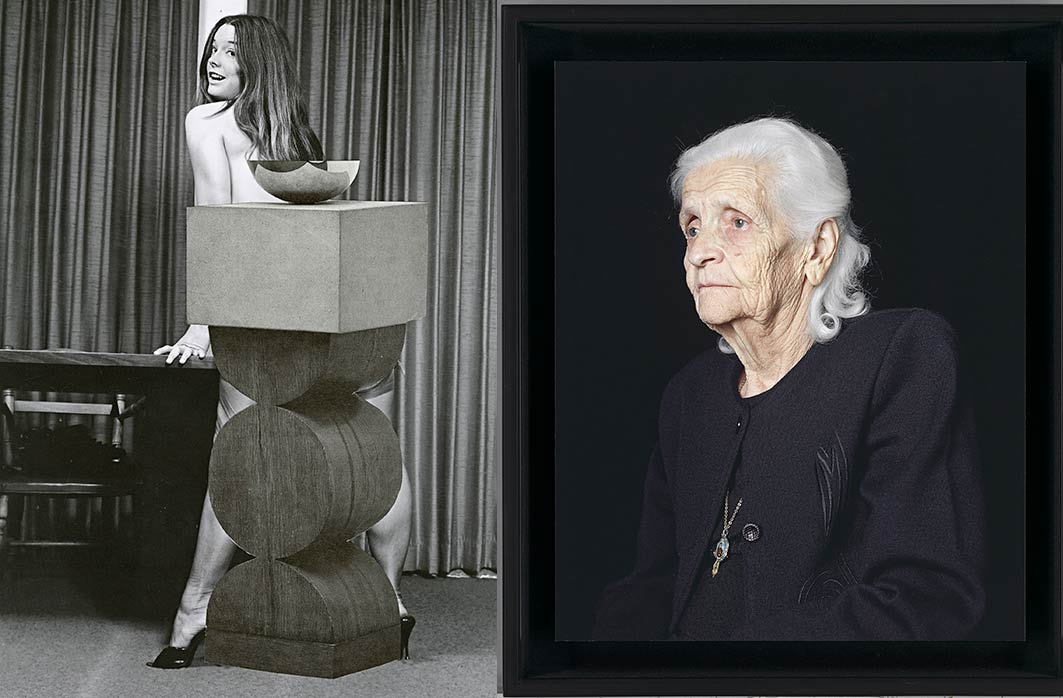

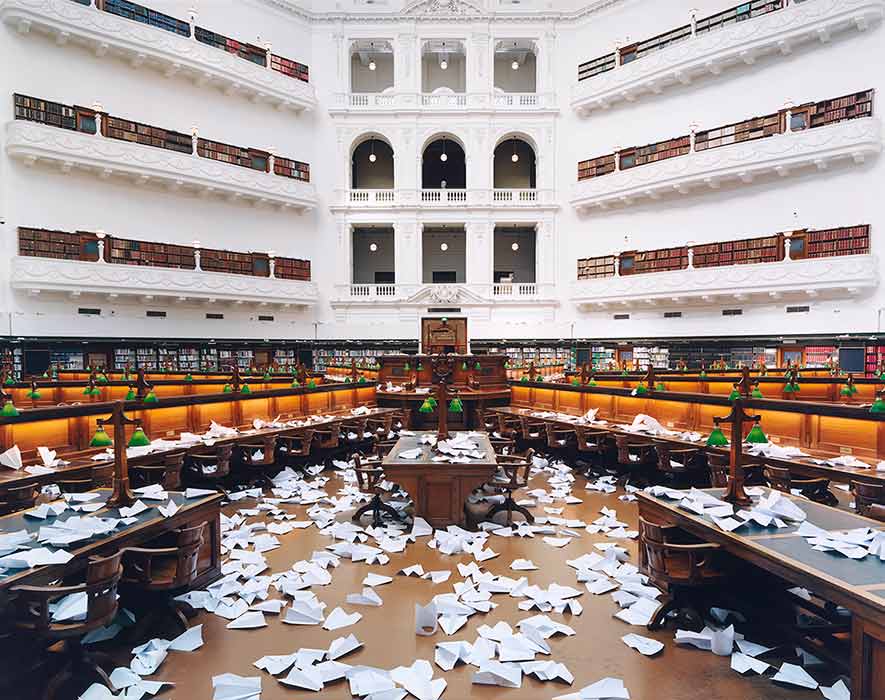

Some of the highlights of the exhibition come from its willingness to downplay its own grandeur. Stuart Ringholt's series of conveniently covered nudes (pictured) contributes to a welcome sense of cheekiness that stretches to many of the included works. Ross Coulter's 10,000 Paper Planes documents the beautiful aftermath of launching 10,000 paper planes from the mezzanine of the LaTrobe Reading Room at the State Library, and Darren Sylvester asks audience members to just lose their inhibition and dance with his amazing light-up dancefloor fittingly titled For You.

However, all this light-heartedness doesn't undermine other works with much heavier themes. Georgia Metaxas' photographic series The Mourners (pictured) is heartbreaking in its depiction of women following the death of their husbands. Penny Byrne examines the dark side of nationalism by disfiguring kitsch figurines in iProtest. Then, Destiny Deacon offers up a dark installation about stereotypes of Indigenous identity; her work is just one of many fuelled by a sense of postcolonial anxiety.

So what does this have to do with Melbourne again?

Before seeing it, the premise of Melbourne Now sounds a little ludicrous. These works really aren't all connected to Melbourne like you might imagine, and the goal to "reflect the complexity of Melbourne and its unique and dynamic cultural identity, considering a diverse range of creative practices as well as the cross-disciplinary work occurring in Melbourne today" sounds like one of those intimidatingly broad VCE exam questions: 'What is art?' or 'Examine World War Two in 500 words or less'.

There are some pieces, of course, that examine Melbourne in a more literal sense. Jon Campbell plasters a wall in customised tea towels that invert and challenge our inherent sense of Australiana, and there are a number of pieces that explore laneway culture including street art and local activism. In an encouraging show of democracy and civic engagement the artwork Zoom even asks audience members to decide 'How Might We Design Our Future City?'.

But, the thematic concern of Melbourne is secondary to Melbourne Now's examination of contemporary art itself. As the NGV are often concerned with competing on a global stage with regular announcements of European masterpieces, it's incredibly reassuring to see them so involved with contemporary Australian art in this way. Melbourne Now is the kind of exhibition we need open forever — the kind of showcase that keeps audiences in touch with a diverse range of new artwork and practices. This is art relevant to us.

Image credits from top, left to right

Tully Moore, Chevron, Goggle, Kaws, Universal Habit, 2013 (installation), oil on canvas cotton, chrome, plastic 178.0 x 108.0 cm, © Tully Moore, courtesy John Buckley Gallery, Melbourne.

Patricia Piccinini, The Carrier, 2012, silicone, fibreglass, human and animal hair, clothing, 170.0 x 115.0 x 75.0 cm, Collection of Corbett Lyon and Yueji Lyon, Lyon Housemuseum, Melbourne, proposed gift, © Patricia Piccinini, courtesy Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne, Photo: Peter Hennessey, Supported by Corbett and Yueji Lyon.

Kinonak, Melbourne (fashion house) Australia est. 2011, Amie Kohane (designer), Kiwaa dress, 2013, from the Free-Time Collection Spring- Summer 2013-14, Collection of the artist, Supported by MECCA Cosmetica © Amie Kohane.

Stuart Ringholt, Nudes, 2013, collage, (1-52) 29.0 x 30.0 cm (each) Collection of the artist, © Stuart Ringholt, courtesy Milani Gallery, Brisbane.

Georgie Metaxas, Untitled 28, 2011, from The mourners series 2011, type C photograph, 60.0 x 50.0 x 7.0 cm, Collection of the artist, © Georgia Metaxas, courtesy of Fehily Contemporary, Melbourne.

Ross Coulter, 10,000 paper planes – Aftermath (1) 2011 type C photograph, 156.0 x 200.0 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Purchased NGV Foundation, 2012, © Ross Coulter.

Melbourne Now is open 'til March 2014. Works are on display at both the International and Australian spaces of the NGV and entry is free. For more information head to the Melbourne Now website or download the app.