Exit Interview: Bek Conroy on the End of Bill and George

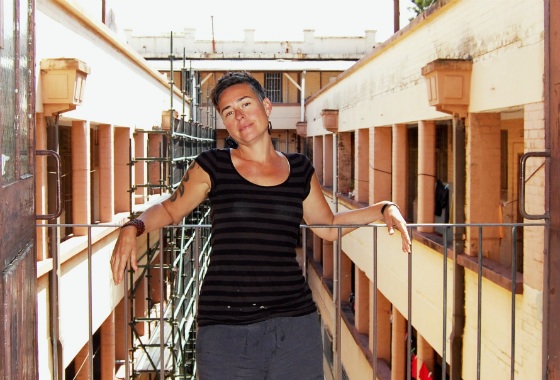

As an iconic artist space closes its doors, Bek Conroy reflects on five years in Redfern.

Bill and George has closed down. Not long ago, during the Surry Hills Festival, the former artists' workspace and sometime venue held its farewell party, a week after a jumble sale to get rid of everything it's former residents couldn't take away with them. Earlier artist space Lanfranchi's famously closed with a bit of a bacchanal. Bill and George's last party was vivacious, but a bit more low key.

What working artists will do without inner city spaces like her former workspace is a big deal, according to writer, artist, creative director and space-runner Bek Conroy. At the end of her time in Bill and George, Concrete Playground chatted with her about the history of the space, as she hands back the keys and closes the door for the final time.

What is the life of a creative space? For Bill and George, five years. The space occupied a Redfern warehouse loft, around the corner from Prince Alfred Park. Walking up a fire escape staircase you'd find yourself in a welcoming, but off-centre, space that encompassed artist workrooms, a kitchen and a long central common room/sometime performance space. Out the back, at the other end of this industrial complex, is a light-filled central courtyard ringed by terraces of cheap accommodation.

Like most artist spaces Bill and George had originally faced a dilemma: fringe properties are cheaper and the vagaries of cheap real estate give you a bit more leeway. (Lan Franchi's saw the upside of thus: "A regular landlord would not have put up with the kind of stuff we were doing.") But since artists are part of the gentrifying wave in a city, their presence bumps up the price. So they, in turn, get bumped out by the rising rents. Or — as was the case for Bill and George — they find themselves staring at starkly more expensive options at the end of a five year lease. Artists bring the vibe that brings investors.

Because of this, government funding should be helping artists, says Conroy, talking about the recent TAFE funding cuts to art, because there's a return for the investment: "If anything, an intelligent city would be increasing funding around investing in it because they're precisely the areas that are going to bring lucrative accumulation of wealth."

Bill and George has seen good times and rockier ones in the time since it opened. It's been a vibrant art space occupied by working artists and other arts professionals from around Sydney. The space wasn't on the radar unless you moved with a certain crowd, went to the right festival or knew one of the artists. But it's been an icon among its generation of art spaces.

When it first opened, the South Sydney Herald wrote about Bek Conroy — the charismatic and loquacious woman who, more than anyone, became synonymous with the space — as a "veteran" of an art scene that had then recently "lost a number of artist-run initiatives like the Wedding Circle and Pelt in Chippendale, Space 3 and Lan Franchis".

When I talked to her five years later, in a now-empty corner office of the same space, she was downbeat about letting go of the work that the collective had put into maintaining and improving the site. "It's sad that we have to leave behind all of our collective labour."

When the gallery signed a five year lease in 2007 it was in a pretty different state. "It was dark, because there was no electricity. It was just disgusting. There were dead cats, dead rats. There was about a ten centimetre layer of pigeon shit." It took five men seven days to clear the pigeon shit. Then they installed a kitchen, cleaned the walls, refitted the empty bathrooms, installed their own security grills reconnected the water and started building partitions.

Five people were central to founding the space: Conroy, Mark Taylor, Caitlin Newtown-Broad, Clare Perkins and Hosannah Heinrich. They started looking for a location in April 2006 and signed the lease in 2007. "We came in here and it was pretty much love at first sight." says Conroy. They borrowed $25,000 to cover renovation, and the bond. The directors also put in a month's rent each, as starter money.

To begin with, they used the space as a venue. Kaz Therese curated Kiss Club, Heinrich ran tango milongas and the second Imperial Panda Festival staged the Ballad of Backbone Joe.

But the decision to fly under radar came at a cost. For the third Imperial Panda Festival, Bill and George was due to host local stars the Brown Council, but was tipped off that the council knew that they were running a "multifunction art space". The City of Sydney was one of Imperial Panda's sponsors. Twelve days out, they had to cancel. The cease-and-desist letter came soon after.

So they started hosting smaller, semi-private events. An Ampersand launch (Alice Gage had been running Bill and George's small press library until Ampersand got off the ground). Meet the artist. Bedtime stories fundraisers. Kiss Club moved offsite.

The space had actually been in the process of lodging a DA. It was, eventually, left unsubmitted. They couldn't get all parties on board. Running unofficially had been a simple decision. "If you can get away with not doing it, you're much better doing that. Once you start having to comply with stuff, then you actually are set up so, if you don't comply, you get penalised. Whereas doing it without a DA, you only risk getting penalised. I mean, you get penalised either way." Conroy reckons that to have run it completely legally would have cost them up to $100,000. Four times their starting budget. Alcohol licenses, public liability: these were similar issues to those overcome with difficulty by contemporary (performance) space the Red Rattler.

During its lifetime Bill and George's reach was pretty wide. Interviewing Conroy for this piece, the space began to seem omnipresent. As well having met Conroy through mutual friends, I found I knew one of the current residents and two more of its founding members. One of these, Taylor, I knew especially well via the Sydney Latin American Film Festival. I'm sure other people have found themselves similarly entangled with the space. It's not an unpleasant feeling.

What's happening to the former tenants? Some are looking for new workspaces. "Alex, one of the artists here," says Conroy "He's moving to a new warehouse in Marrickville. People are temporarily setting up. People are storing their stuff at their parents' house. I mean, these are mid-career artists who are doing this shit. I mean, this is terrible."

And, like other professionals working around the city, it gets worse when you ask about where people live away from the workplace. It's not just a few who lack a reliable residence. According to Conroy, almost none of them do. "No one here has a reliable place to live. There is one artist who's recently acquired property. One. He inherited it."

And on the end of Bill and George? "I think it will definitely leave a hole. I think it will be replaced. The turn over happens. We accept that. That's part of the changing landscape. But the worry for us, and for every artist in Sydney, is the pace at which that is happening. [The end of a space] fragments the community. Every time. It haemorrhages resources. It haemorrhages people.

"The wealth of the city is heavily contingent on creatives remaining in the city. You can't buy in that sort of organic culture. Land value has to come down in the CBD. Otherwise, we are going to lose artists. They're just going to leave. They are already leaving the city. And that's the position I'm in. I'm looking toward moving to Detroit."

So that's what's next for Conroy, the CBD, Marrickville or Detroit?

"Yeah." she says.