Five Indigenous Artists Making Strong Statements in Artbank's Timely New Exhibition

Contemporary Indigenous artists speak out about hidden histories and ongoing injustices in 'Darkness On The Edge Of Town'.

In partnership with

"What we don't acknowledge becomes the shadow within ourselves," says Western Australian curator Clothilde Bullen. "And that is what has happened in this country. We have to more openly have these conversations, in order to bring these histories into the light."

Pieced together from the Artbank treasure trove and complemented with select loans is a new exhibition curated by Bullen, showcasing the work of contemporary Indigenous artists. Darkness on the Edge of Town will explore narratives of marginalisation and the positioning of the Indigenous Australian. It's a timely exhibition that will excavate hidden histories and reflect on continuing injustices.

Bullen was drawn to create an exhibition that responded to the ongoing injustices against Indigenous people. "The works are highly political in nature," she says. "When I started this exhibition, I was looking at the Black Lives Matter movement and SOS Black Australia."

What is striking about many of the works on display is their dark aesthetics — shades of black and grey ripple through paintings, photographs and sculptures. "A lot of history is very murky — there are parts people choose not to know about it," says Bullen.

In revising the white-washed version of Australian history, Bullen's exhibition is all about restoring and elevating black voices. "I would like there to be an understanding that within these spaces, and within Australia, these are important voices that matter," she says. "Our voices are front and centre — they are embedded within the history of this country. Let's not participate in the great forgetting."

Darkness on the Edge of Town runs August 18 to November 12 at Artbank Sydney. Bullen took us into the Artbank store for a peek into the exhibiting artists and what to expect from this complex, highly timely exhibition.

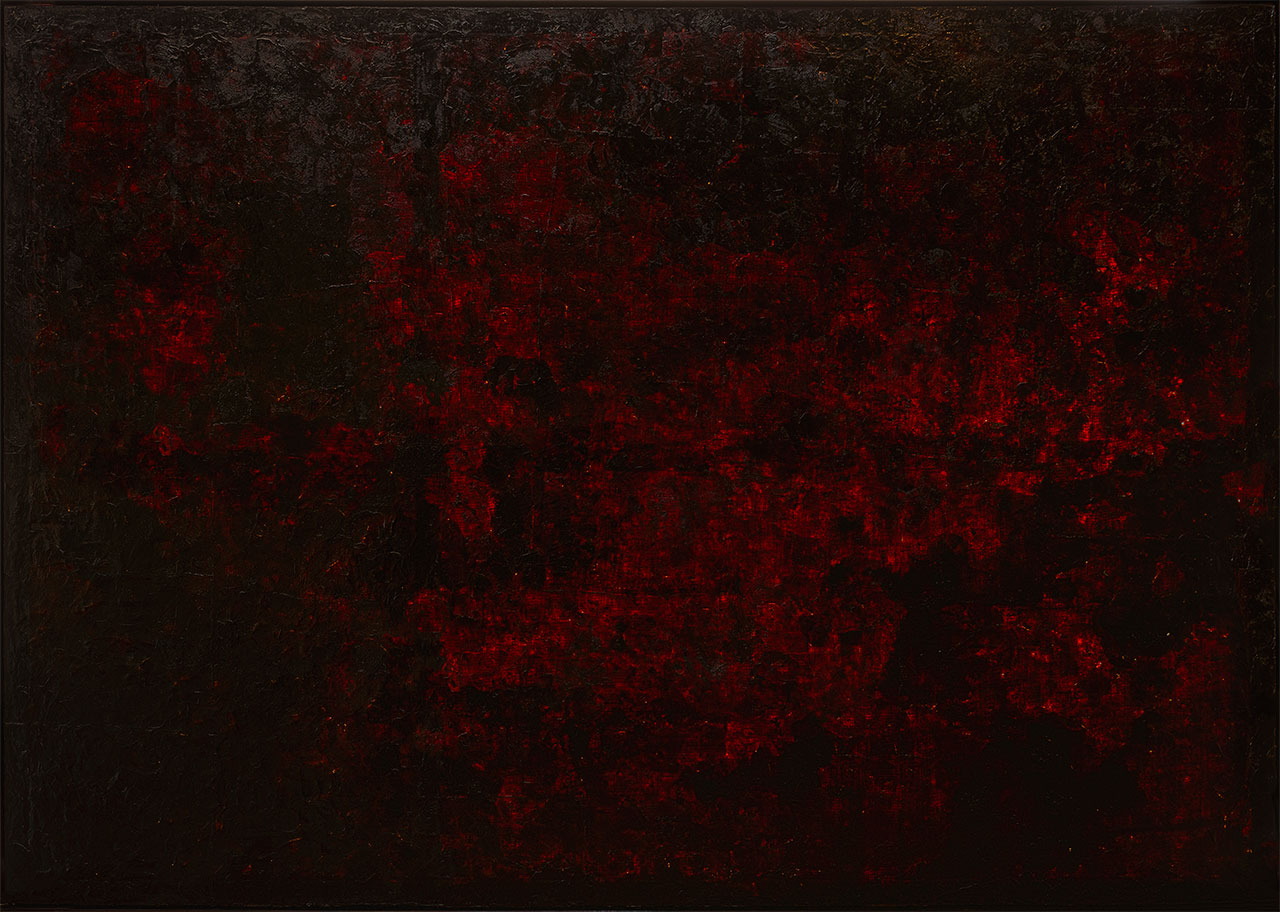

Christopher Pease, Balga resin (2008), Artbank collection

CHRISTOPHER PEASE — BALGA RESIN

Looming large over this exhibition is a painting from Wardandi artist Christopher Pease. This heavily textured work was created through a labour intensive process of collecting resin from the balga or grasstree, which is native to Southwest Australia. Pease then melted the resin onto hessian and canvas, creating a dramatic visual effect.

"The resin is actually a living thing," says Bullen. "This work changes every time you look at it and in different lights. It has different personalities." From one angle, the sumptuous and bioluminescent painting looks like purple veins pulsing through black paint. Under a different light, it looks like a red lightning strike cracking open the darkness. "The materiality tells a lot of the story," says Bullen. "In terms of the way the resin is bound to the hessian, the work speaks to a connection to country and how that has changed over time."

James Tylor, (Erased Scenes) From an Untouched Landscape #5 (2014), Artbank collection.

JAMES TYLOR — ERASED SCENES (FROM AN UNTOUCHED LANDSCAPE) #12

James Tylor is quickly becoming one of Australia's most eminent young photographers. In this series, Erased Scenes (From An Untouched Landscape), his moody and mysterious photographs look like documents from a crime scene investigation. Of course, there is a sophisticated political critique that binds these works together. The geometric black shape imposed onto each image omits the presence of Aboriginal people and culture, paralleling their omission from history and society.

"The immediate sense you get when you see these works is that something is missing — the country is incomplete. Alternatively, something has been laid over the top," says Bullen. "So there is either a hidden history or something we want to blank out. What goes on in that blackened space? What has been forgotten? As simple as these works look, they are embedded with multiple levels of meaning."

Lorraine Connelly-Northey, Narrbong (String Bag) (2007), Artbank collection.

LORRAINE CONNELLY-NORTHEY — NARRBONG (STRING BAG)

Lorraine Connelly-Northey's sculptural practice begins with sifting through discarded materials: fencing wire, barbed wire, rusted iron, metal meshing. Salvaged mainly from farming lands, these industrial materials are typically used to demarcate property. In this way, her objects contain a powerful commentary on the territorial impact of colonisation.

Connelly-Northey's intricate sculptures are modelled on traditional Aboriginal artefacts. For instance, her reimagined narrbong references the string bag once used to collect water. "We have these traditional objects that we can't necessarily make anymore," says Bullen. "Our culture is dynamic, it's not static. This work is an example of we can utilise whatever we can in order to make something that is going to work for us. This exemplifies the practice of using ideas around traditionalism and manifesting them in completely new and contemporary ways."

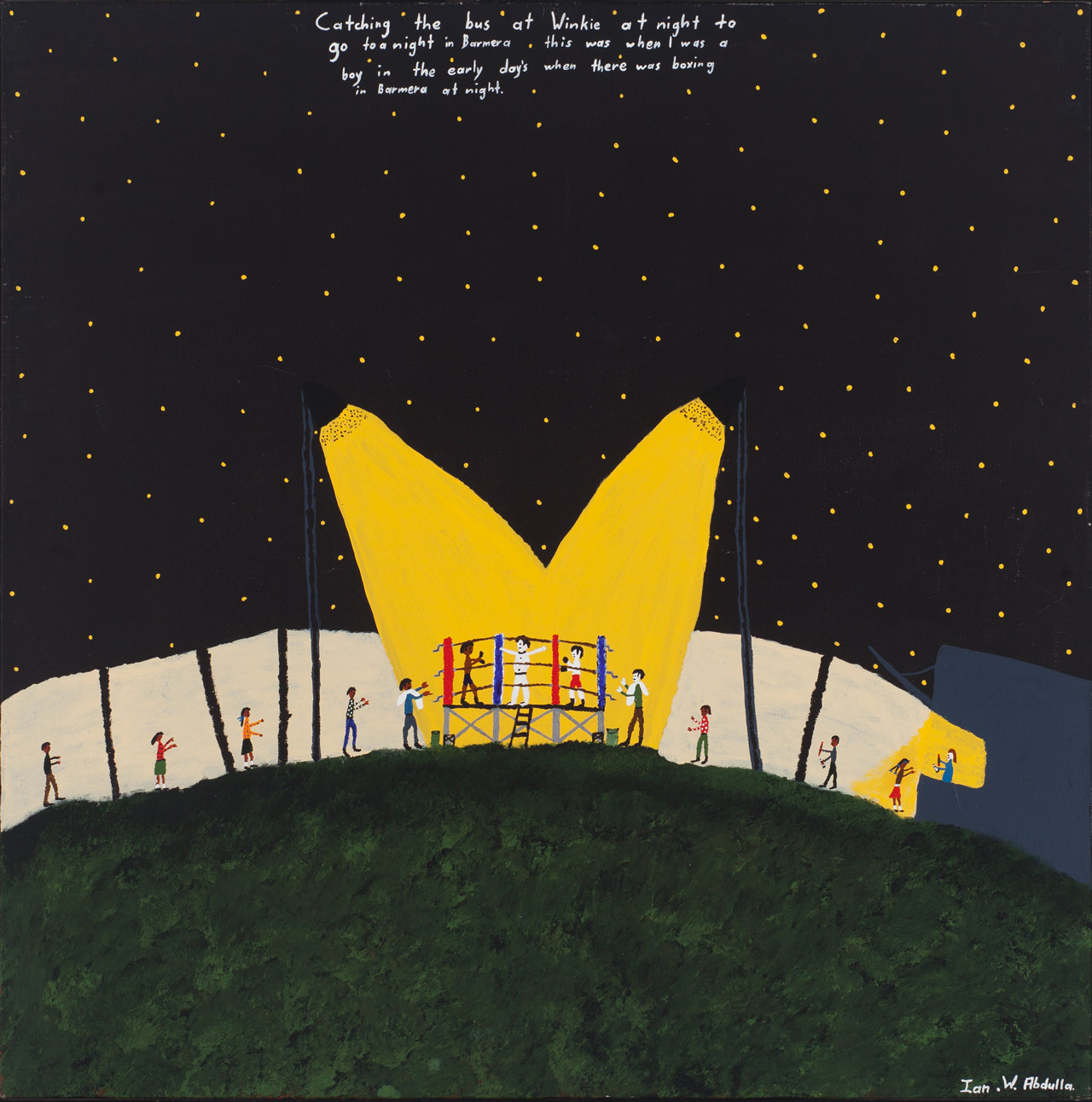

Ian Abdulla, Night Boxing (1992), Artbank collection.

IAN ABDULLA — NIGHT BOXING

Rooted in a specific historical phenomenon, Ian Abdulla's work traces the culture of tent-boxing in Aboriginal communities. This bareknuckle sport, which was frequently illegal, arose around 1900 and continued until the late 1980s. "In reference to the title of the exhibition, we're talking about fringe dwellers," says Bullen. "These were people who were kept out of town at night and were asked to exist on the edges."

While the history of tent-boxing is a complex one, Abdulla draws attention to a self-sufficient practice, which unfolded outside the control of authorities. In this way, it provided an alternative set of fiscal structures beyond the mainstream. "To me, this work makes a nice comment on what you need to do in order to be economically viable," says Bullen. "Tent-boxing was a meaningful cultural tradition for people all over the country."

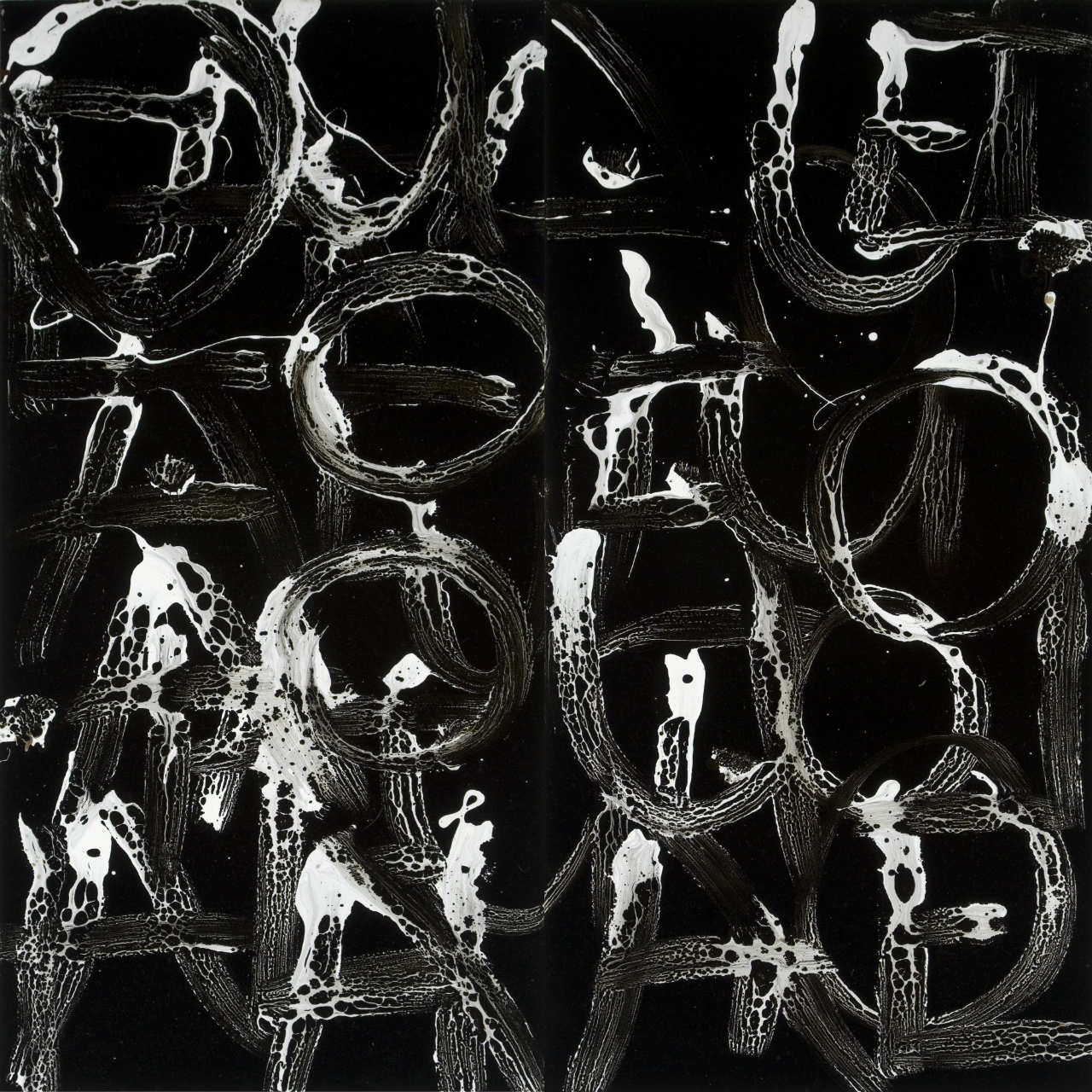

Clinton Nain, What are you saying? (2007), Artbank collection.

CLINTON NAIN — WHAT ARE YOU SAYING?

In scrutinising the scars of dispossession, Clinton Nain's practice confronts the darkest elements of Australian history. In particular, his painting, What are you saying? is a sombre take on the linguistic assault on Aboriginal languages. "Nain uses materials that are found in missions and reserves," says Bullen. "Then he turns them around to create strong messages about the colonial history of this country. While this work looks quite abstract, it's a critical statement about families being in missions and the stolen generations."

Using bitumen and bleach — an uneasy combination — Nain's painting contains a political message that evokes the attempted conquest of white over black. "The medium is quite expressive and matches the content," says Bullen.

Darkness on the Edge of Town runs August 18 to November 12 at Artbank Sydney.

Images: Kimberley Low.