Concrete Playground’s Summer Reading Guide

Concrete Playground duly presents our suggestions for the best books to read over your summer.

The days are long and drenched with sunlight, and you've got time on your hands to lie on the sand or in the grass and while it away with a book into the late summer hours. But you want the hours to be worthwhile, and sometimes it's really difficult to make a decision or to know where to start. Moreover, you want something enjoyable and easy to read that isn't going to turn your brain to marshmallow.

So to help you out, Concrete Playground has come up with some suggestions for the best books to read over your summer. We've got new stuff and old stuff. Books you've never heard of and books everybody's heard of. Romances, mysteries, high quality smut, and stories both sweet and weird and wonderful. Compiled lovingly by somebody who's found the first legitimate use for her English major, we hope that these books delight you and make summer all the more wonderful.

The Savage Detectives by Roberto Bolano

If you've spent time in inner-city bookshops over the past couple of years, you've probably noticed a slow infiltration of the name Roberto Bolano onto every 'Recommended' shelf around. It's been a long time since an author has taken on cult status quite like Bolano has. When once asked what me might have done had he not become a writer, Bolano answered "a homicide detective. I would have been the sort of person who comes back alone to the scene of a crime by night, unafraid of ghosts." He said that just a few months before his untimely death in 2003, and ever since Bolano's ghost has been figuratively haunting international literature.

The Savage Detectives is one of his greatest works. Divided into three sections, the novel is ostensibly about the adventures of two young Mexican poets from the 1970s until the turn of the twentieth century, as they drink, have sex, travel the world, and argue long and loud, narrated solely by the people they come into contact with. Written in luminous, ferocious prose, you have never read anything like The Savage Detectives before. If you read nothing else this summer but for the newspaper and the labels on bottles of cider, please, we implore you, read this.

Citrus County by John Brandon

John Brandon is one of 'those McSweeney’s guys'. Trumpeted by Dave Eggers, amongst others, as a kind of modern-day Catcher In The Rye (but then, isn’t everything?), Citrus County pulses with the heat and humidity of the backwaters of Florida. Combining your standard narrative of lonesome adolescence with the most sinister kind of crime novel, Citrus County has become something of an underground literary sensation.

The story follows Toby, a fourteen year old with a case of minor delinquency, and his tentative relationship with Shelby, the new girl in his class. The catch is that Toby has kidnapped Shelby's four-year-old sister Kaley and hidden her in a bunker in the woods. The story emerges out of the sluggish apathy of the swamps and sun and hits you like a slap in the face, completely subverting your expectations about what novels are 'supposed' to do. It is at once 'easy to read' when it's too hot to think too hard, while also being a very, very good book.

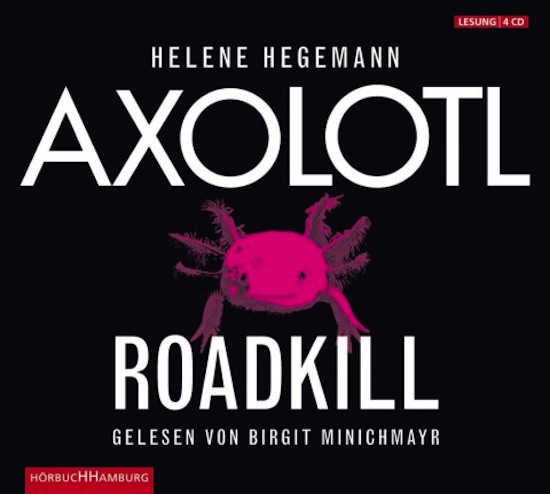

Axolotl Roadkill by Helene Hegemann

Axolotl Roadkill, both when it was published in its original German two years ago and then translated into English earlier this year, was smothered in hype, like so many chips soaking in a puddle of cheap pub gravy. For one thing, the book was written by a seventeen-year-old girl, a filmmaker from Berlin who comes across as both bone-achingly cool and distressingly talented. For another, it's a bit like the first season of <em>Skins</em> in novel form. One effusive reviewer aptly praised Hegemann for "conjuring dialogue like David Mamet, romanticising the afterlife like Jack Kerouac and hallucinating as sadistically as the Marquis de Sade." That just about sums it up.

Axolotl Roadkill is at once a portrait of a young girl so emotionally stunted there’s no hope for a happy ending or any kind of redemption, and also a broader critique of a society which prefers to float along on the surface of things, refusing to grow up or to ever really care about anything too deeply. The novel isn’t perfect – and got waylaid with nasty accusations of plagiarism which Hegemann, playing semantics, termed 'mixing' – but it is savage, and raw, and completely worth reading, regardless of the suffocating hype.

Outer Dark by Cormac McCarthy

Cormac McCarthy has the uncanny ability to render both horrific and beautiful descriptions from the same bloody, violent subject matter, in all of his novels. The sentences are long, heartwrenching rambling things which read as though a desert mystic is spinning them out of the threads of the dark universe around him. For that is very much the image of Cormac McCarthy, arguably the world's most adored misanthrope. While his more well-known novels are those that have been adapted to cinema, like The Road and No Country For Old Men, Outer Dark, his second novel, is worthy of just as much rapturous attention.

Set somewhere in the deep south at the turn of the century, Rinthy gives birth to her brother Culla's baby, who abandons the baby in the woods. The novel follows the two of them, wandering separately, looking for the baby and attempting to assuage the sin. The world of Outer Dark is one abandoned by God, with no causality, and where human beings are indistinguishable from animals. It may be disturbing and unsettling, but Outer Dark is one of the finest things you could read over the next few stifling months.

The Heart is A Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers

Regularly included in lists of the top 100 English language novels of the 20th century, The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter was a sensation when it was published in the 1940s, propelling Carson McCullers, a waif-like twenty three year-old in androgynous clothing, into the throes of the literary spotlight.

The novel centres on a deaf man, John Singer, in a Southern small town during the depression. Four characters - one an alcoholic labourer, another the owner of a diner, a black doctor and a young, idealistic teenage girl - all flock to him, each believing that he is the only person in the world who can truly understand them, despite not being able to hear a single word they say. No matter the heartache each character expresses, one thing comes across: the bitter loneliness and isolation that plagues the lives of the most disparate people, who cannot connect.

Office Girl by Joe Meno

In some senses Office Girl is a little like a Zooey Deschanel movie. It's a little bit twee, but not in an un-endearing sense. The semi-experimental novel published by Joe Meno earlier this year is the story of two former art-school kids in late '90s Chicago. Both ride around the city on their bikes, Jack recording the sounds of everyday life, while Odile defaces public advertisements with pictures of hairy genitalia.

Often a little absurd and self-conscious, the novel is also an affectionate portrait of what it's like to be creative and lost in your twenties. Appropriately enough for a novel about people who want to change the world through art, the novel comes complete with photographs by Todd Baxter and illustrations by Cody Hudson.

Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell

Cloud Atlas was published almost nine years ago, so it's hardly a new phenomenon, but given that the film version has just been released, there has never been a more apt time to read the book before you go to sit in a cinema and gaze adoringly at Ben Whishaw while appreciating the sheer moxy of the Wachowskis and Tom Twyker in adapting such a profoundly unadaptable book.

The novel is composed of six different story lines, structured in a pattern very similar to Italo Calvino's If on a winter’s night a traveller, but with the added feature of a 'mirror' effect. Stretching from the nineteenth century into a post-apocalyptic future, and dabbling in genres as various as crime, science fiction and South Pacific adventure, each narrative ends abruptly at a moment of suspense, only to be returned to in the second half of the book. Completely original and endlessly entertaining, Cloud Atlas is definitely worth toting around with you to the beach until the pages get logged with sand.

Blindness by Jose Saramago

Blindness by Jose Saramago

Saramago won the Nobel Prize for literature back in 1998 and remains one of the only Nobel laureates whose work is truly enjoyable to read. Blindness is one of his best-known works.

In an unnamed city at an unnamed time, an epidemic of blindness begins to sweep through the population, an infection seemingly spread from just looking upon a blind person. For the safety of the rest of the city, the government locks up those afflicted in an abandoned mental asylum in the middle of the forest, fighting an increasingly hopeless battle and leaving them at the mercy of themselves. Eventually conditions degenerate, and the inmates are left to roam the devastated city trying to survive. On the most simplistic level, the blindness is allegorical of lack of sight, from a man who lived through dictatorship, and revolution. In this world it is the small heroisms of individuals that count.

NW by Zadie Smith

Although nothing Zadie Smith has written, arguably, has equalled her debut novel <em>White Teeth</em>, her books are reliably excellent. NW is all about roots, specifically about what it's like to be from North West London, where with its halal butchers, African hairdressers and housing estate blocks, seems a world away from the clean white avenues of central London.

The novel follows four people now in the their mid 30s, all raised on the same housing estate, over the summer of 2010. Like the streets of North West London itself, the things which happen in the story are fractured and volatile, and there are only tentative conclusions. Seen across the complexities of race and class, NW is also about the kind of angst and disillusionment of people who are told they're supposed to be happy, yet can't feel it, let alone see it.

Pulphead by John Jeremiah Sullivan

Pulphead is a collection of long essays, which, when you say it just like that, doesn’t sound like a particularly riotous thing to read. But the essays in Pulphead are those of a man styling himself as a next generation David Foster Wallace, Jon Ronson or even Hunter S. Thompson. They are, in short, brilliant.

With a wit and energy rarely present in journalism, Sullivan takes us to a Christian rock festival and Tea Party rallies. He races across the south in search of obscure lost blues musicians and nineteenth century botanists and then a few pages later we find him pondering the origins of Axl Rose and Michael Jackson. The stories in Pulphead form a journey through the back roads and badlands, with John Jeremiah Sullivan, a journalist previously published in The Paris Review and The New York Time, undertaking a quest for some kind of enlightenment in the parts of America we rarely see or even acknowledge.