Overview

We're always drawn in to the works at White Rabbit, and this exhibition is no exception. Artists in Hot Blood present works looking at the irreverent and the sublime, the public and the private, on subjects stretching from gaming to sperm donors, video avatar gods to solitude, neuroscience to desire. Hot Blood shows us we are alive, and viscerally so — in all the realities we exist in: physical, digital, spiritual, and psychological.

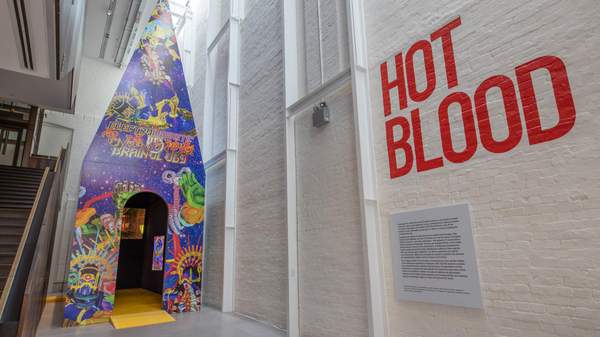

LU YANG 陆扬: ELECTROMAGNETIC BRAINOLOGY (2017)

Lu Yang's piece beckons as you enter the gallery. Lu explores the intersection between science and the spiritual in a purely digital, pop-culture video collage. A five-channel video plays in a stickered, custom-built structure that reflects the churches in which Lu usually presents her work in China. Referencing the Japanese otaku subculture, Lu used free online programs to create God-like avatars that she then cuts into a world of hyper-saturated colour and video-game soundtracks. Deities of each of the five elements, or wu xing (五行) — wood, fire, earth, metal and water — deliver sermons on neuroscience and medical technology. As phrases "the amygdala can destroy", "water god", "autonomic nervous system" and "self-transformative power" drift in and out of your thoughts, Lu's turbo-charged animated characters perform, their at-times jagged outlines a hint that this mesmerising digital world is something more than seamless pop-culture to be consumed without question.

ZHU LIYE 朱利页: LINE-UP (2007)

For Line-Up, Beijing artist Zhu Liye wanted to find ordinary people from different professions and walks of life to photograph. This proved difficult, so instead she used life models accustomed to sitting for students at the Central Academy of Fine Arts.

The work is a play between soft and hard, drawing attention to the male body as an object rather than the ubiquitous female nude. The photograph's format, cropped into a circle, might also reference the round pictures, known as tondi, that became popular during the Renaissance. Tondi allowed artists to emphasise the centre of the image, and often featured religious or decorative content.

Zhu brought in elements of performance art to create the light-hearted energy she desired for this piece. While shooting the work, we're told she playfully ran around the set in bell-bottom jeans and a bra, a mental-image-counterpoint to the comically serious faces of the men standing to attention in her photograph. Zhu says the men very quickly lost their initial shyness and 'performed' as directed.

HUANG HUA-CHEN 黃華真: THE FAMILY ALBUM—SO SEE YOU LATER (2009–12)

Quiet oil paintings at first glance, on closer inspection these works hold a deep sadness. Made over three years, Huang Hua-Chen's paintings draw on memories of the father who abandoned her as a small child. His presence in each work is sometimes seen, sometimes felt, and is summarised by a central figure in an oval-shaped black frame, a presentation used traditionally in China for ancestral portraits to represent someone who has died. Huang says a deceased father is one who didn't leave.

The unsettling quality and pared-back palette of Huang's works brings to mind Belgian painter Luc Tuymans who also works from photographs. Huang paints in a style which obscures facial features to make her figures unrecognisable, drawing the focus to what isn't painted and leaving meaning open to interpretation. In one picture, a baby hangs suspended. Her swaddling is clasped in an adult's hands, but the space below suggests the possibility of being dropped.

HU LIU 胡柳: GRASS (2015)

Hu Liu uses pencil to create her work. Each piece takes months to complete, consuming thousands of pencils. The significance of this isn't apparent until you draw closer and the reflective surface of the work reveals itself as paper entirely covered with the metallic lustre of graphite. Hung opposite a painting of the sea, you as the viewer float suspended between the two works.

Liu references the Daoist belief in harmony between yin and yang, dark and light — saying, "to know whiteness yet preserve the blackness is to be the model for the world". We think of blackness as an absence of light and colour but this black swims with a carbon sheen almost like petrol. Things are not always what they seem and, as Haruki Murakami said in his Hans Christian Anderson literature award acceptance speech, "just as all people have shadows, every society and nation, too, has shadows. If there are bright, shining aspects, there will definitely be a counterbalancing dark side." It is by considering and embracing both the dark and the light that we can understand our experience.

JIU SOCIETY 啾小组: JIU BOBO (2015)

Jiu Society is a group of three artists, Fang Di, Ji Hao and Jin Haofan. All born and raised in Shenzhen, the highly modernised city fast becoming the industrial and technological heart of modern China, in this work they re-enact a viral North Korean video. A small child performs, singing "Daddy loves me, Mummy loves me, love me, kiss me and hug me". In this work, these words "become a satirical song of praise to their city against a backdrop of demolition, new construction, propaganda slogans and a looming statue of Deng Xiaoping". The adults singing the song are overlaid with video of what looks like Shenzhen seen through the cross-lines of a tourist camera, as ghostly appearances reminiscent of Jesse Kanda's 3D creations swim in and out of view.

Some works in White Rabbit's Hot Blood exhibition may be disturbing to viewers. Gallery attendants are there to guide you and answer questions.

Hot Blood runs until August 4 at White Rabbit Gallery.

Top images: Electromagnetic Brainology (2017), Lu Yan; Loufu Dream–Pink Pink (2006), Liang Tao; Expected Departure (2004–16), Leung Mee Ping; Guggen' Dizzy (2009–11) and A Route of Evanescence (2015), Mia Liu; Life (2001–11), Yin Xiuzhen; Bees (2010–12) and The Bearable (2007–10), Chen Zhe; Problematic GIFS–No Problem at All (2016), Miao Ying.