Summer of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)

Questlove jumps behind the lens with this exceptional documentary, which brings footage from the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival — aka "Black Woodstock" — to the screen.

Overview

UPDATE, October 9, 2021: Summer of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) is available to stream via Disney+, and is also screening in Sydney cinemas when they reopen on Monday, October 11.

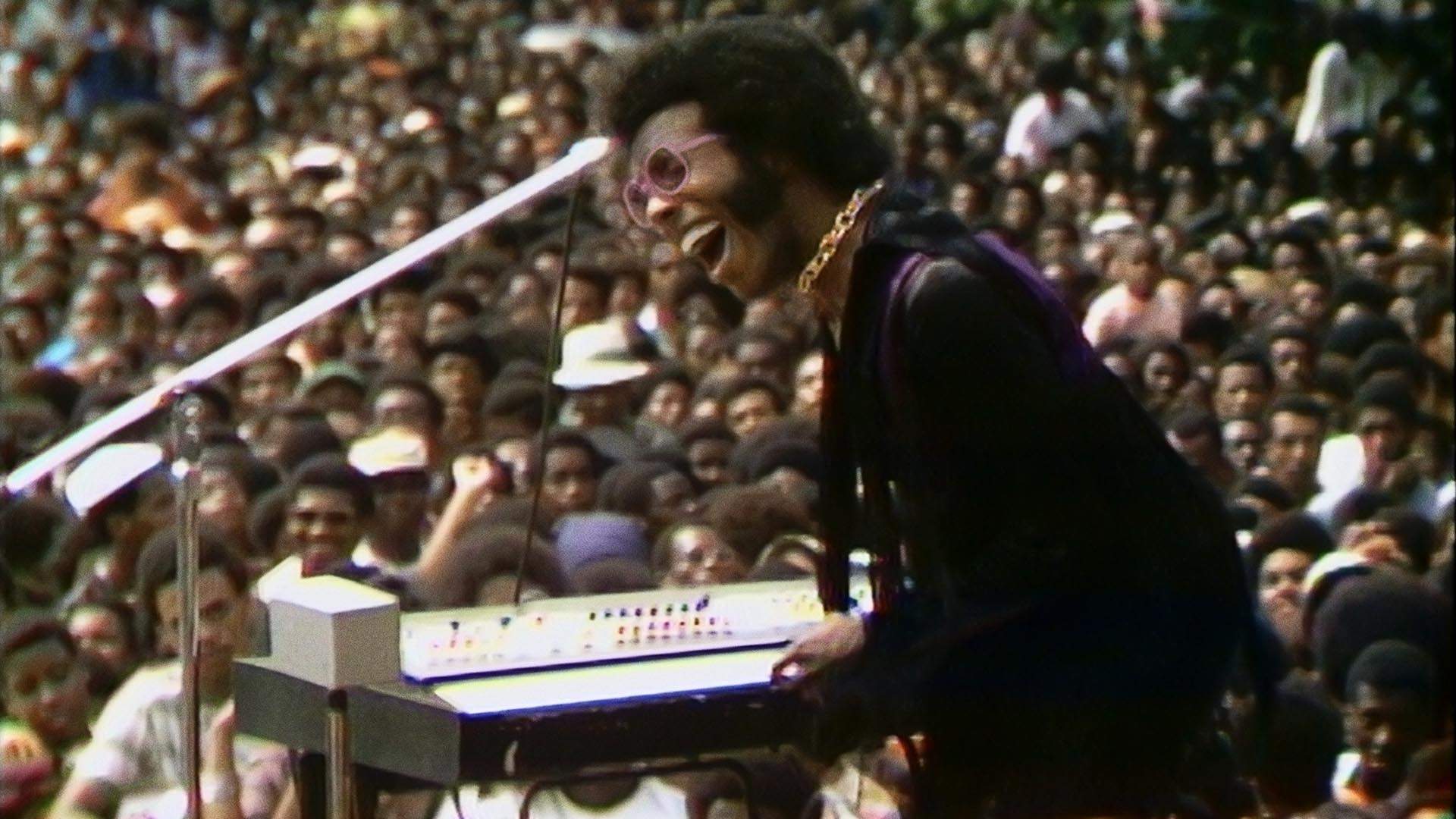

Much of Summer of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) involves stunning archival footage, as recorded more than five decades ago, capturing live performances by an astonishing lineup of musicians. At the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival, a free series of gigs that rolled out across six weekend and saw around 300,000 people head along, Nina Simone, Stevie Wonder, BB King, Sly and the Family Stone, the Staples Singers, Mahalia Jackson and Gladys Knight & the Pips all took to the stage — among others — and the newly unearthed reels that immortalised their efforts are truly the stuff that music documentary dreams are made of. For his filmmaking debut, Ahmir 'Questlove' Thompson could've simply stitched together different songs from various sets across the festival, and let those music superstars lead the show. He could've taken the immersive, observational approach as Amazing Grace did with Aretha Franklin and her famed gospel gigs, and jettisoned context. But The Roots frontman and drummer doesn't make that choice, and he ensures that two words echo strongly throughout the film as a result: "Black Woodstock".

Also in New York — upstate in the town of Bethel, 100 miles north of Harlem — Woodstock itself took place in the summer of 1969 as well. The Harlem Cultural Festival kicked off before and kept playing after its better-known counterpart ended, but comparing the two events makes quite the statement. Why has one endured in public consciousness and proven pervasive in popular culture, but not the other? Why did footage of one quickly get turned into a film, with the Woodstock documentary first reaching cinemas in 1970, but recordings of the other largely sat in a basement for half a century? Why did television veteran Hal Tulchin, who shot the entire Harlem Cultural Festival from start to finish on four cameras loaded up with two-inch videotape, get told that there was little interest in releasing much from a "Black Woodstock"? (One New York TV station aired two hour-long specials at the time, but that's all that eventuated until now.) These questions and the US' historical treatment of people in colour go hand in hand, and whenever the words "Black Woodstock" are uttered, that truth flutters through Summer of Soul. Here's another query that belongs with the others: why was such an important event left to fade in memories, and in broader awareness, to the point that many watching Questlove's exceptional doco won't have heard of it until now?

Consider Summer of Soul an act of unearthing, reclamation and celebration, then. It's a gift, too. The archival materials that are so critical to the film are glorious, whether a 19-year-old Wonder is tickling the ivories; a young Staples is singing with Jackson, her idol; The 5th Dimension are breaking out matching outfits while crooning their 'Aquarius' and 'Let the Sunshine In' medley; or Simone is delivering her anthem 'To Be Young, Gifted and Black' with fierce passion. Powerful moments featuring immense talents like these keep popping up, including The Temptations' David Ruffin singing 'My Girl', and Reverend Jesse Jackson introducing Jackson and Staples' rendition of 'Precious Lord, Take My Hand' by giving a eulogy for Martin Luther King Jr. These are slices in time that everyone — every music lover, every fan of every single artist featured and everyone in general — needs to see, and now can.

Savvily, Questlove also weaves through an exploration of the whys and hows not just behind the Harlem Cultural Festival, but also surrounding its lack of attention since. Where he can, he chats to the musicians, canvassing their recollections and reactions. Just as crucial: his interviews with attendees, many of whom were kids that were taken along by their parents. These festival-goers reflect upon how strong the event remains in their childhood memories; how it shaped them, their music tastes and their personalities afterwards; and the sense of togetherness that floated through the shows with the summer breeze. Their reminiscences tie into the broader discussion into New York City at the time, America's political climate — MLK was assassinated a year earlier, and Black Panthers acted as the festival's security — and the determination within the Black community to champion itself at every turn. Journalist Charlayne Hunter-Gault even shares her fight to get The New York Times to print the term 'Black' as pride around it grew. Also covered: the moon landing, and the conflicting sentiment about whether it was a giant leap for humankind or a wasteful step that spent money that could've been better put to use on earth (and specifically in Harlem). Indeed, this is a portrait of an era, a neighbourhood and its people as much as it's a window into one essential and historic festival. As its subtitle notes, it's also a snapshot of a revolutionary mood.

If there's one misstep here, and it's just one, it comes from a few contemporary snippets of commentary that don't add anything beyond the obvious. Most movies can be improved by getting Lin-Manuel Miranda involved, but the Hamilton and In the Heights visionary's insights into the potency of music aren't needed here — because the footage, and the tales from the people who went to the Harlem Cultural Festival, say it all anyway. Questlove finds plenty of time for shots of the crowd, showing their response to the sets playing onstage, and all those jubilant faces and swaying bodies paint the strongest picture there is. Unsurprisingly, Summer of Soul captures their joy with an impassioned rhythm. Its director is also a DJ and music director, after all (including at the 2021 Oscars), and he knows where to bob in and out of tracks, vibes and refrains. When the film ends with one festival attendee watching footage from the event and exclaiming "I'm not crazy!" because he now has proof that this oft-overlooked "Black Woodstock" was real, it's the ultimate mic drop. Wanting to devour every second of material that Tulchin shot all those years ago is a clear side effect, though.