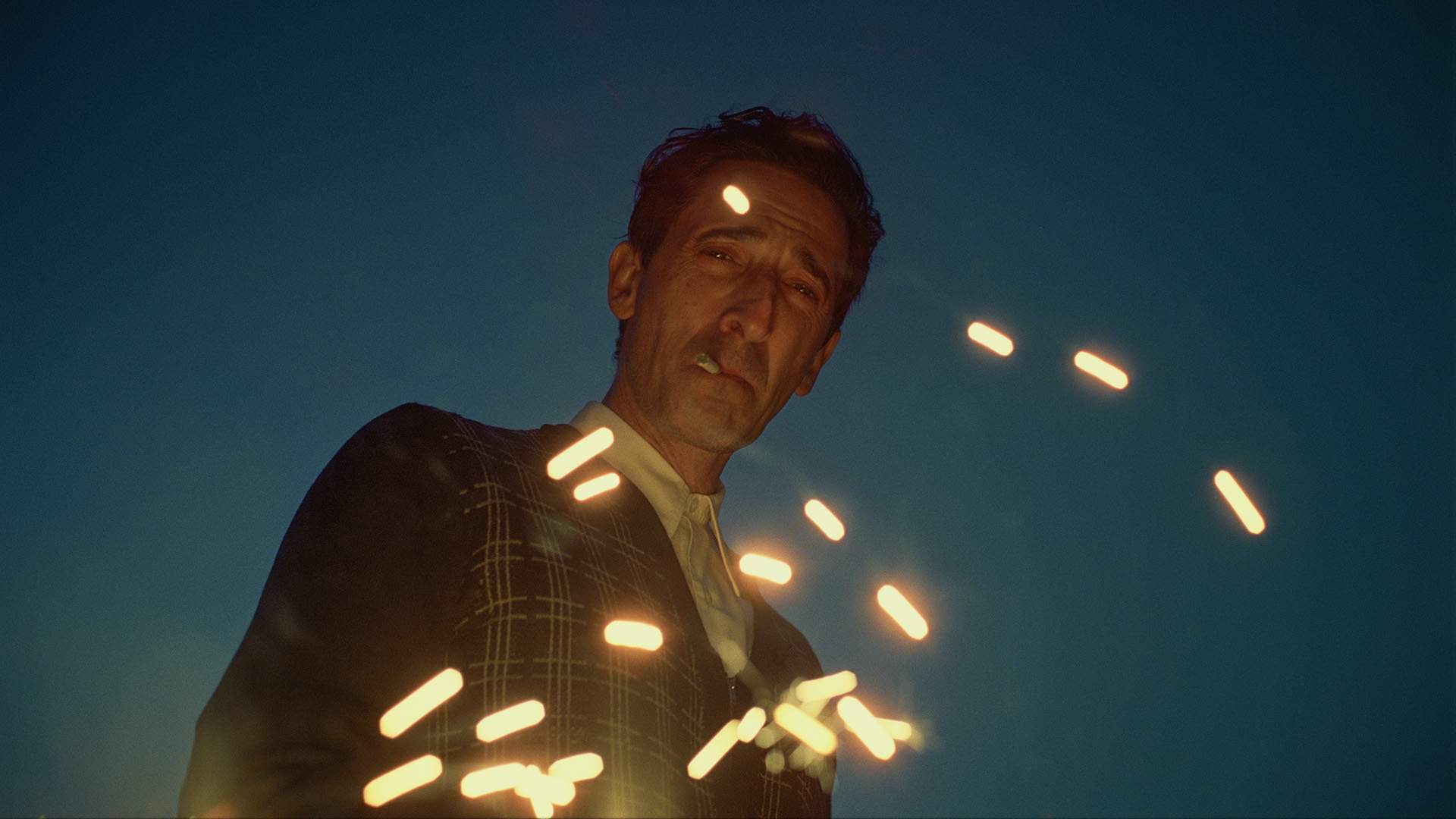

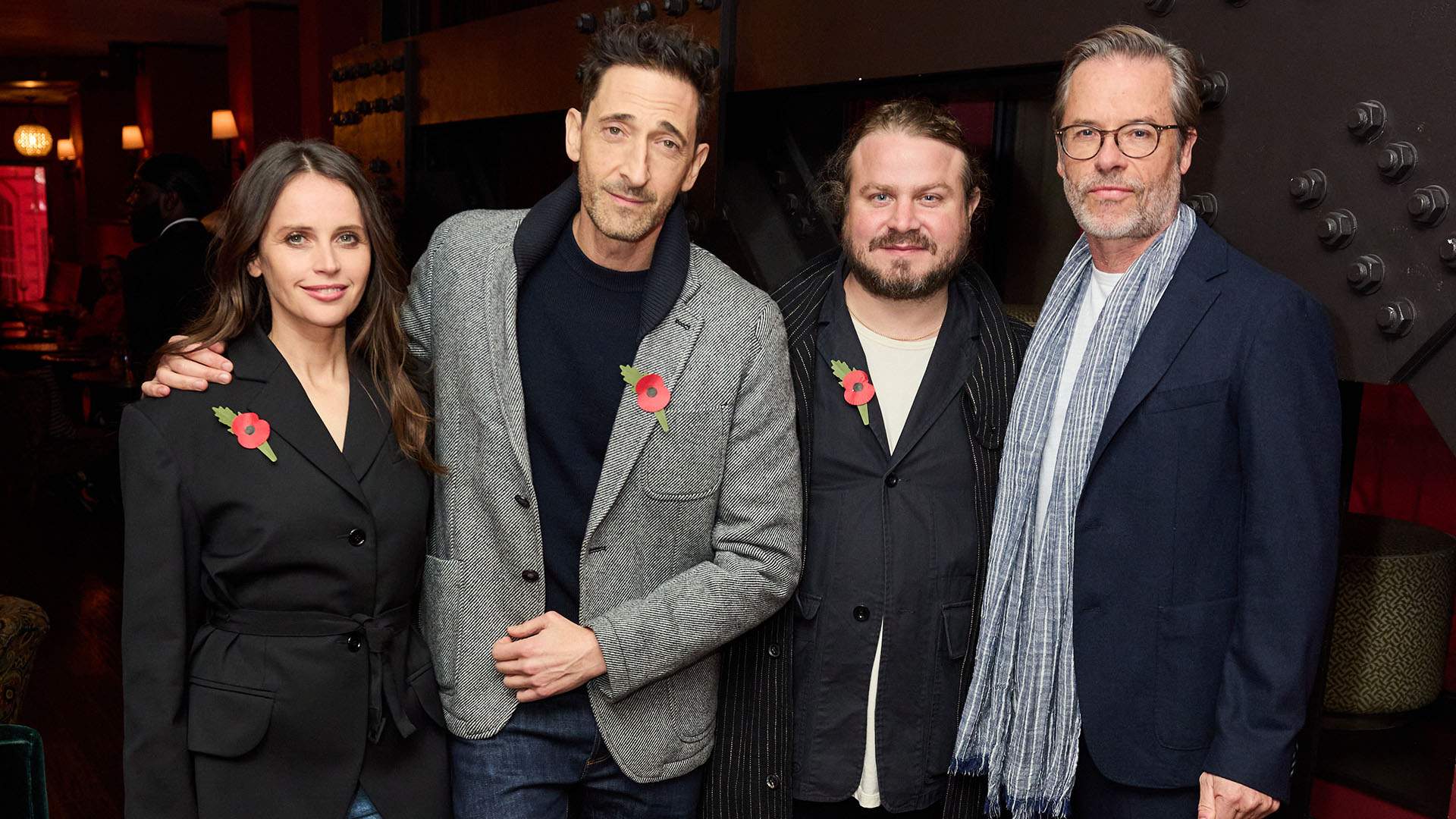

Constructing a Monumental Reckoning: Adrien Brody, Brady Corbet, Guy Pearce and Felicity Jones Talk 'The Brutalist'

This ten-time Oscar-nominee is epic in its ambitions, performances, images, length and exploration of pursuing the American dream post-war — and yet also deeply intimate.

As the world heard in brief at the 2025 Golden Globes, the path to The Brutalist becoming the acclaimed film it is — it won three awards that evening, for Best Picture — Drama, Best Director and Best Actor — Drama; since, it has earned ten Oscar nominations and nine BAFTA nods — was far from smooth, let alone guaranteed. "Once, a few short months ago, it had the odds very much stacked against it," filmmaker Corbet said in his first speech of the night. "I was told that this film was undistributable. I was told that no one would come out and see it. I was told the film wouldn't work," the actor-turned-director, who previously helmed The Childhood of a Leader and Vox Lux, added in his second stint at the microphone. "No one was asking for three-and-a-half-hour film about a mid-century designer, on 70-millimetre."

When The Brutalist premiered at the 2024 Venice International Film Festival, it started lining its trophy cabinet. No shortage of five accolades went its way at the fest, including the Silver Lion for Best Direction. That debut screening was the moment that stars Adrien Brody (Winning Time: The Rise of the Lakers Dynasty), Guy Pearce (The Convert) and Felicity Jones (Dead Shot) realised how a movie that'd always felt epic to them also resonated deeply with audiences, they tell Concrete Playground. "You felt it, you felt it in the room," says Brody, who knows a little about the response from viewers to a feature that grapples with the Second World War's impact. In 2002 at Cannes, he went through a similar experience with The Pianist. In 2003 at the age of 29, he became the youngest-ever Best Actor Academy Award-winner for that picture, a title that he still holds.

The Brutalist is epic not just in its emotions — for everyone involved in crafting it and for audiences alike — but also in its ambitions, performances, imagery, and exploration of the harrowing post-war pursuit of the American dream and immigrant experience. The same description applies to its lengthy running time, which includes a 15-minute intermission. It's the monumental feat of a committed filmmaker who worked for years to ensure that the movie came to fruition, and in exactly the way that he wanted it to. While it screens in 70-millimetre, it was shot VistaVision, a format deployed by Alfred Hitchcock on masterpieces such as North by Northwest and Vertigo, and last used in the US for an entire feature with 1961's One-Eyed Jacks.

"The shortest answer is really just because it looks better," Corbet shares with Concrete Playground about using VistaVision. "Essentially, what you're doing is you are turning the negative on its side so that you're able to use the length of the celluloid, you're able to use more neg area," he continues. "I actually think it's a great alternative for independent filmmakers that want to shoot on a large format," he notes, while also recognising what every devoted movie lover does: that how a film is made and looks are crucial tools in ensuring that watching pictures on the big screen still thrives. "For me, large formats are the future of cinema. What's funny is that they're both the past and the future. They've been around for almost a century at this point … It gives folks a reason to get off their couch, and I think that's really important in this day and age."

Giving the world something to behold is also a key facet of The Brutalist's narrative, with Brody playing Hungarian Jewish architect László Toth. To escape the horrors of the Holocaust, he crosses half the planet to start a new life in America, making Pennsylvania his home while waiting for his wife Erzsébet (Jones) to complete the same journey with their niece (Raffey Cassidy, a Vox Lux alum). Professionally, his past achievements in Europe mean little in the US, however, until being tasked to revamp the personal library of rich and powerful industrialist Harrison Lee Van Buren (Pearce) leads to a stunning commission. For his new patron, László is to design a sprawling hilltop community centre as a memorial to Van Buren's late mother.

As grand as The Brutalist is, it's also an intensely intimate movie, as the ways that the Toths are shaped by the traumas of both the Second World War and their efforts to settle in America haunt in every moment. That makes it personal for Brody, whose family made the same trip to the US. "I can relate to the immigrant experience and the hardships and sacrifice and resilience of the many people who have been forced to flee horrific conditions in hopes of finding a new land, and to be welcomed and to find a sense of home. Obviously, you must have heard me speak of my mother and my grandparents' own personal struggles of fleeing war-torn Europe in the 50s and being refugees, and coming to America and starting again, and so I can speak to that. And I can speak to how by reflecting on the horrors of the past we can hopefully gain some perspective and clarity and understanding of how to make the world better in our present. And I think that's what filmmakers are yearning to discover and open a conversation towards," he advises.

Brody also sees how personal this film is to Corbet, as the feature's director and co-writer — penning the script with his partner Mona Fastvold (The World to Come) — has never held back from conveying. "If you ask Brady, the creation of this film is very much an exorcism of his experiences in the dynamic of the patronage system as an auteur filmmaker with a sense of being dominated and controlled. I'm merely an actor at this juncture of my life, and I understand that that is a somewhat par for the course. There are things worth fighting for, and the joy and the burden of being a filmmaker is that you are at the helm; however, there are other factors, as you need funding to do great work. I think the key really is just communication and respect. And when that isn't there, it leads to great differences and acrimony."

"This is a very emotional work, and deeply committed work. And whenever you're that passionate about anything you have to stand up for what's important and your beliefs. So I relate to it. I also understand nature of the space," continues Brody. We also chatted with him, Corbet, Pearce and Jones about gleaning the magnitude of the film even from the script, how the polarising response to brutalist architecture influenced the movie, unpacking such layered characters, architecture as social commentary, those Venice reactions and more.

On Knowing Even Just on the Page That This Was an Epic Project, Yet Also Deeply Intimate — and the Magnitude of What It Was Asking of Brody

Adrien: "I think you could just re-interpolate your question into my answer. It's exactly how I feel. It was very much, it was incredibly moving to read for all those reasons. It was quite nuanced and eloquently written and sensitive, intimate and vast in scale, and unique.

I mean, there was a built-in intermission and overture, you name it. It was such richly written screenplay.

Of course this character has a complexity, and such a range of lived experience that any actor would would kill for this role. I was very, very moved by it. It spoke to me in many ways. It was very ambitious in scale and very challenging, and I was very impressed, and I thought it had great potential."

On How the Polarising Response to Brutalist Architecture Influenced the Film — and Also How Corbet Approached the Movie

Brady: "Well, two things. I suppose that I really relate to this movement because of the fact that I myself, I make films that are generally somewhat polarising, and they have a very strange construction, and an intentionally jagged one. I deliberately omit second acts and play with structure in ways that I think for some viewers, they find it incredibly frustrating.

But I think that that brutalism's radical commitment to both good, clean minimalism, but they take up a lot of space and they're very unapologetic, I think that for me, that's not just what this film is but it's what my films are, and so I relate.

And then finally, in terms of how to present it, the difficult thing about architecture is that architecture is inanimate, it doesn't move — and so it is very difficult to make a film on architecture, because even if it it's incredibly glorious, it's nothing like the human face. So I think that for us, we had to find ways of representing architecture, that the film itself had to be a brutalist monument. Because there's only about eight or nine minutes of brutalism in in the entire film's runtime.

For me, we are representing our architecture in terms of our forced perspectives and emerging from darkness into the light, in the way that Lloyd Wright would lead people through a space. In a Frank Lloyd Wright residence, you would enter into a small room with very low ceilings and no windows, and this was a place to take off your shoes and hang up your jacket. Then you would ascend a staircase and then boom — it would crack wide open like a cathedral.

That's very similar to our opening sequence with Adrien emerging onto the deck of a ship. It's a similar feeling. So we were constantly thinking about ways to represent the architectural experience."

On Pearce Making Back-to-Back Films with The Brutalist and Inside Where Complicated and Hierarchical Power Dynamics Between Men Are Pushed to the Fore

Guy: "It's just the most-fascinating thing to be interested in, I think. And I find it's not that I'm looking for those roles per se, but just that both the scripts came my way and I was immediately taken by them.

Felicity will attest to this one as well, it's just so interesting the way with all the characters, in the way that Brady, who wrote the script with his wife Mona, has a deep interest in the connectivity and the dynamics between people, and the way in which we need each other and the way in which we use each other, and the way in which we sort of rely on each other.

All that stuff is is a big part of what this story is, as well as some themes and other great stuff, too.

And I think on the film Inside, which is a really emotional, beautiful movie as well — it's a prison movie, these men in prison, very particularly trying to work out who's in charge, where the power sits and shifts, and really it's just fascinating stuff to delve into.

Really, as actor, it's sort of the best stuff to delve into, I think."

On What Jones Drew Upon for a Film That Examines How Layers of Different Traumas Shape Us

Felicity: "I find research incredibly helpful. I like to be quite forensic in terms of understanding the context of the character and the time that they're existing in. And I feel in quite a sort of scholarly way, I like to go from the outside in, so go 'what are the big, themes, ideas, in the script and the character?', and then gradually get more and more detailed as the as time goes on.

But when you're actually shooting, you just have to be totally focused on that psychology and intricacy of that person. But what's so great about working with someone like Brady is that he understands the power of cinema to convey ideology.

And that's really special to work with someone like that, whether the film has obviously a much bigger socio-political message than its individual components."

On the Challenges of the Role, and Making Independent Films, for Brody

Adrien: I think the hardest thing about this part is that it went away for a long time. I read this script five years ago and then there was an iteration of it without me and others, and then there was a long period of time and it came around, and I'm very grateful for that.

It's very challenging to make independent films. Obviously you have a deficit of resources and a bounty of creative visionary ideas, and you have to make the most complex and eloquent story come to life. And you, as an actor, it really falls on your shoulders quite a bit, because the production being starved of resources pushes you to the limit.

So they're constantly forcing calls, meaning there's not much turnaround time, so you're working all the time. And if you have vast amounts of dialogue or heavy emotional scenes day in and day out, it's quite draining. And there isn't sufficient time to really give everything the space that it needs, so you have to make do and be incredibly prepared, especially when you have a very specific dialect to work on and beautiful eloquent dialogue.

So there are those issues, but it's not something I'm unfamiliar with. Most films that I've done have been in similar circumstances. And you just do the work.

I don't look back at this with — I feel very grateful for it, and I think part of the journey is what you do with those challenges and how you can have them motivate you and, at times, even enhance your own work because of those pressures."

On Corbet's Use of Architecture as a Form of Social Commentary, and Also a Metaphor for the Characters

Brady: I think that the jumping off point for this film, it came from two books, each from a small press. One was called Marcel Breuer and a Committee of Twelve Plan a Church, which is a memoir that was written by a monk at Saint John's Abbey that observed a lot of the microaggressions that Marcel Breuer was facing, or was up against, when he was building that cathedral. And as a Hungarian Jew in a small American town.

Then I also read a book from Jean-Louis Cohen, who's written many, many extraordinary pieces on architecture, and he did the big Corbusier book for Taschen that you see in rich people's living rooms — but he also wrote a book called Architecture in Uniform, which is an extraordinary book about the ways in which post-war psychology and post-war architecture are intrinsically linked. It's also about how buildings were employing materials that were developed for life during wartime, and so a lot of these materials that were developed for the First and Second World War had a big impact even on the construction of these buildings in a more literal way and a less allegorical way.

But he also writes about his interpretation of a lot of work from that, and for him, it's a question as well: how cognisant is the artist of what it is that they are expressing, especially with these particularly radical monuments? And so that's what the film for me is ultimately really about. The sort of meaning that his niece imbues the building with at the end of the movie, it may be an interpretation — and he, at that point, he's in a wheelchair and his wife has most likely passed away, and so he's not able to speak for himself.

I think that movies and architecture, they are pieces of public art, and people will do with them whatever they will. They paint on them and they will piss on them, and they cherish them and they will tear them down. And at the end of this character's life, you're left with question of 'was it worth it? Why do we do what we do?'.

And I don't have the answer to that because I don't know why I continue to make films when it's so frequently an arduous and painful experience. But, you know, I'm already working on the next one."

On How Pearce Approached Digging Into Van Buren's Complex Layers

Guy: "I never know how to answer the question of how I approach something. I think a lot of it is instinctive. A lot of it is as a response to the script and what I felt was there in the script.

There's very clear moments throughout the course of the film where the character almost contradicts himself in behaviour, but in each of those moments, I think he exhibits something that is, to some degree, true to himself — whether he's bombastic and dominating, or whether he's actually sensitive and kind of aware, whether he's being generous or whether he's controlling. All of those things tie in together, and I think that that's what was great about the script for me, was that I felt like I saw all these different elements in this man that Brady and Mona wrote.

And so obviously approaching each of those scenes at individual times, it's important to be true to whatever it is that's required in a scene, but also being aware of how he is in the scene previously, and that we want to see contradictions, I think, in characters, but then it needs to feel like a believable leap from from one place to another.

Here is somebody who is, I think, deeply sensitive in a way, and kind of aware, but also has a big ego and is driven by his own sense of self-creation. I just felt like I got all of that from the script and obviously in talking to Brady, so it's an internal thing that takes over for me when I'm working, that just hopefully allows me to be authentic with all those different elements."

On Jones' Task in Taking Erzsébet From a Woman Who Appears Fragile to a Powerful Presence Standing Up for Her Husband

Felicity: This was something that Brady and Mona were really intrigued by, this idea that when Erzsébet arrives, we see how the trauma of being in the concentration camps has manifested itself, and that manifestation is very clearly physical. She's suffering from malnutrition, and in many ways it feels as though Erzsébet has disassociated from herself physically. I think she's been through such trauma that in some ways, she's slightly watching herself in the beginning of the film.

And she has such little expectation of other human beings. She decided if you don't have any expectations, then you can't be disappointed. So in that first scene when she meets Van Buren, she has just realises that in quite a Nietzschean way, that this is just a power struggle. Every human interaction to her is a power struggle. So you've just got to work out what someone is potentially, what harm they're going to do to you, and how to mitigate that.

But then throughout the film we see her, conversely to Laszlo, we see her health improving. We see her flourishing. And you realise that this woman is a deep pragmatist, and in some ways she's someone who is prepared to embrace the joys of capitalism that America is advertised to offer. And you see her, in some ways, having to deny her own intellectual progression in her work just as a means of getting enough money so that they can make their lives work.

By that scene that she has with Van Buren, you see someone who's just refusing for the hierarchy to be financial, that dignity does not come from in any way your perceived financial prowess — it comes from something much deeper."

On the Connections That Corbet Sees Between The Childhood of a Leader, Vox Lux and The Brutalist

Brady: "They're all virtual histories. The Childhood of a Leader is a post-war film as well, about the six months leading up to the signing of the Treaty of Versailles. Vox Lux is also about a post-traumatic period of a more-recent world history, about American culture after 9/11 and Columbine, which were such definitive events in the US.

So I would say that the films, they all always begin or conclude from — they're all films on the theme of destruction and regeneration.

One of my favourite essays is from WG Sebald. I talk about Sebald a lot because I'm really a Sebald fanatic, and I also love VS Naipaul and many, many others, but he wrote this fantastic book called on the Natural History of Destruction, and there are these extraordinary essays about regeneration and trauma, and that just is something that I've always been consumed with."

On When Brody, Pearce and Jones First Realised the Impact of The Brutalist with Audiences

Adrien: Only in Venice, to be honest. I wish I could say I'm cautiously optimistic. I've realised now that I'm not even very optimistic. I think it's a good defence mechanism. But I love Brady's work, and I knew the great potential of storytelling, and I knew that he had all of the elements to bring this to life. And yet it did exceed my expectations.

I think it's a combination of all the creative contributions made on this movie, and how they all lift each other up and hold each other together beautifully. It's quite remarkable.

To share that experience in that darkened room in Venice with an audience, and to feel — you felt it, you felt it in the room. Those are really memorable moments in one's career, when all that hard work, and it's not just the hard work of making this film. It is 20 years since I've sat in a room and witnessed that for a film that I was the protagonist in, that spoke to such complexity and touched the people around me to the point where they're weeping and looking at me and in awe of this work. And it's beautiful."

Guy: "I think Venice."

Felicity: "I think Venice. I think the audience response in Venice was quite a surprise. You expect a nice gentle clap, and it was quite forceful and for quite a long time."

Guy: "And it didn't stop. Yeah, it didn't stop."

Felicity: "And then we suddenly were going 'oh wow, this'. So yeah, it was in that moment. 'Something has happened here.'"

Guy: "I think during the process of filming, of course we'd all read the script and we'd been working with Brady on the phone in conversations beforehand — and it certainly felt like we were part of something special. But I've felt that before on jobs and then the finished film doesn't necessarily live up to it. So I think knowing also Brady's style, he's somebody to be reckoned with as far as filmmaking goes.

But yeah, I think Venice really was, I guess, a clear moment to go 'oh, okay'."

Felicity: "Yeah, it's amazing how the festival — I mean, it's such an extraordinary festival, Venice, how much they championed this film and the people involved. And I think that gave us the kick off, really."

Guy: "It helps that there's a bit of Venice in the end of the movie."

Felicity: "Exactly. There's a bit self-interest in it."

Guy: "Yeah, pop a bit of Cannes in your film."

Felicity: "That was very canny of Brady, in fact, to put a little bit of Venice in it."

Guy: "Yes, Cannes-y — Venice-y."

The Brutalist opened in cinemas Down Under on Thursday, January 23, 2025.