The Boy and the Heron

After a ten-year absence from the big screen, Hayao Miyazaki is back from retirement — and still making brilliant and beautiful animated masterpieces.

Overview

For much of the six years that a new Hayao Miyazaki movie has been on the way, little was known except that the legendary Japanese animator was breaking his retirement after 2013's The Wind Rises. But there was a tentative title: How Do You Live?. While that isn't the name that the film's English-language release sports, both the moniker — which remains in Japan — and the nebulousness otherwise help sum up the gorgeous and staggering The Boy and the Heron. They also apply to the Studio Ghibli's co-founder's filmography overall. When a director and screenwriter escapes into imaginative realms as much as Miyazaki does, thrusting young characters still defining who they are away from everything they know into strange and surreal worlds, they ask how people exist, weather the chaos and trauma that's whisked their way, and bounce between whatever normality they're lucky to cling to and life's relentless uncertainties and heartbreaks. Miyazaki has long pondered how to navigate the fact that so little while we breathe proves a constant, and gets The Boy and the Heron spirited away by the same train of thought while climbing a tower of deeply resonant feelings.

How Do You Live? is also a 1937 book by Genzaburo Yoshino, which Miyazaki was given by his mother as a child, and also earns a mention in his 12th feature. The Boy and the Heron isn't an adaptation; rather, it's a musing on that query that's the product of a great artist looking back at his life and achievements, plus his losses. The official blurb uses the term "semi-autobiographical fantasy", an elegant way to describe a movie that feels so authentic, and so tied to its creator, even though he can't have charted his current protagonist's exact path. Parts of the story are drawn from his youth, but it wouldn't likely surprise any Studio Ghibli fan if Miyazaki had magically had his Chihiro, Mei and Satsuki, or Howl moment, somehow living an adventure from Spirited Away, My Neighbour Totoro or Howl's Moving Castle. What definitely won't astonish anyone is that grappling with conjuring up these rich worlds and processing reality is far from simple, even for someone of Miyazaki's indisputable creative genius.

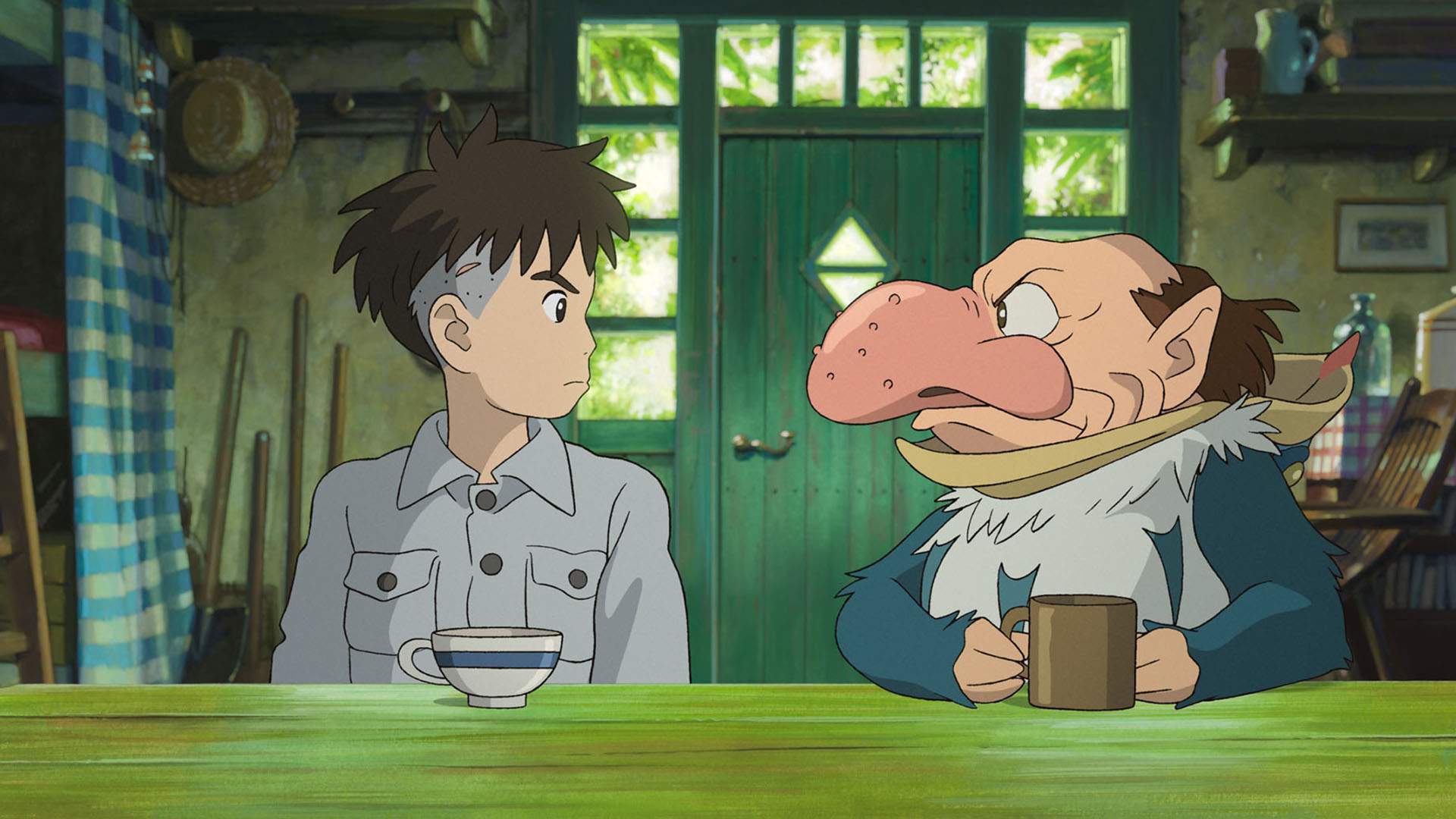

Brilliance fills The Boy and the Heron visually, with its lush and entrancing hand-drawn animation both earthy and dreamlike, and its colour palette an emotional mood ring. Being trapped between two states, domains, zones and orbits recurs here in as many ways as Miyazaki can layer in. This is a film with a raging wartime fire that haunts with its flames, plus a traditional countryside home rendered with such detail that viewers can be forgiven for thinking they could step right into it — and of a tunnel where floating bubbles called warawara wait to be born, pelicans lament the circle of life and masses of people-eating oversized parakeets demand to enforce order. It's also a movie where the titular bird looks as a grey heron should, then flips its beak back like a hoodie to show something less standard loitering. Said fish-eating wader and the eponymous boy frequently make a pair, but the former is also the latter's white rabbit: following the feathered figure does indeed make everything curiouser and curiouser.

Voiced by The Days' Soma Santoki in the Japanese original and No Hard Feelings' Luca Padovan in the English-language dub that's needless for adults but helpful for young children, Mahito Maki starts The Boy and the Heron in Tokyo in 1943 during World War II. And so it is that 2023 delivers two Japanese icons, Studio Ghibli and Godzilla, each harking back eight decades to spin stories steeped in loss and pain that never stops whispering in hearts and minds. As heralded by air-raid sirens, bombings leave 11-year-old Mahito without his mother. For viewers, the tragedy sees Miyazaki nodding to his own mourning for Isao Takahata, his Ghibli co-founder, who died in 2018. Grave of the Fireflies, the studio's greatest film — amid fierce competition and many fellow masterpieces — is not only set during the same conflict but is mirrored by The Boy and the Heron's early moments. How do you live? By knowing what to grasp to, Takahata's old friend posits.

The Boy and the Heron plays like a mix of reverie and memory, as it is, albeit with the second beaming through in emotional truths more than narrative facts. Miyazaki evacuated Tokyo in the war as a boy, however, as Mahito does when his father Shoichi (The Swarm's Takuya Kimura and Amsterdam's Christian Bale) has a new bride in his wife's younger sister Natsuko (Avalanche's Yoshino Kimura and The Creator's Gemma Chan). The change doesn't usher in a reprieve from the quiet and lonely kid's longing for his mum. Instead, it brings the talking heron (Don't Call It Mystery: The Movie's Masaki Suda and The Batman's Robert Pattinson) and everywhere that the creature leads. In a feature with more thoughtful touches than a seemingly endless flock of parrots has feathers, that Mahito's mother and aunt's family estate springs from a great uncle said to have gone mad from reading too many books is quite the inclusion. Stories defined that relative's world, then, which Miyazaki makes literal.

After beginning patiently, Miyazaki also makes following Mahito a tumble down the rabbit hole for his audience. Always inventive as a storyteller and a visionary, the Laputa: Castle in the Sky, Kiki's Delivery Service, Princess Mononoke and Ponyo helmer and scribe's return to cinema keeps besting its spectacle while giving Studio Ghibli some of its most breathtaking images (as set to a score by Joe Hisaishi, who's been doing the honours for the director for four decades, of course). There's no such thing as merely a pretty, dazzling or radiant picture for the great animation house, though. As meticulously controlled as its work is during its creation, with animators sketching in every single thing that's seen, Ghibli is unparalleled in understanding the expressive nature of its chosen medium. In conveying how war, growing up, death, love, fear, isolation, sadness, yearning, belonging, standing out, connecting and just life is a whirlwind of confusion, Miyazaki not only lets his imagination take flight, but his flair. The Boy and the Heron can be as trippy as his company's output gets — and as emotionally raw.

Since 1984's Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, no one has made movies like Miyazaki, other than Takahata. As The Boy and the Heron sails through light and darkness, hope and horror, serendipity and choice, and alienation and acceptance, it also bobs and weaves through many of its filmmaker's trademarks, gleaning that the elements that can unite people and features alike can manifest in as many different ways as an ocean has waves. The pull to retreat then return is the same, whether for a director saying that he's retiring several times (including in 1997 and 2001, after Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away, respectively) or a lost child desperate to flee his hurt and bewilderment. An extraordinary return, and a personal one, The Boy and the Heron isn't expected to be Miyazaki's latest movie now that he's back behind the camera, but it's also the awe-inspiring piece of alchemy that it is because of that history.