19th Biennale of Sydney

Regardless of your thoughts on the Biennale boycott (and if you care about both art and asylum seekers, you probably had a few), the festival's eventual split with long-term sponsor Transfield has come as at least a temporary relief. Now, there is no reason for people to avoid attending the 19th Biennale of Sydney, and to miss out on a wondrous, inspiringly thought-out and immaculately implemented iteration of the event.

Overview

Regardless of your thoughts on the Biennale boycott (and if you care about both art and asylum seekers, you probably had a few), the festival's eventual split with long-term sponsor Transfield has come as at least a temporary relief. Now, there is no reason for people to avoid attending the 19th Biennale of Sydney, and to miss out on a wondrous, inspiringly thought-out and immaculately implemented iteration of the event. Artistic director Juliana Engberg, usually of Melbourne's Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, has a great gift for curation (and communication; you must listen to her speak about the art at some point if you can), and she'll be a tough act to follow.

First off, this is a Biennale that really gets Sydney's obsession with Cockatoo Island. As Juliana would have it, the island is "a fantasy location". It's where we go to play, to be floored by works of scale and to feel far away from the mundane. Perhaps no artwork exemplifies this idea so much as Callum Morton's The Other Side, a ghost train running through the Dog Leg Tunnel. I repeat, a ghost train (!) running through the Dog Leg Tunnel (!!). Entered with great ceremony via a massive Google search window (because Google is the scariest thing now? Not sure), it is oddly understated in execution, but it gets all the points for the temerity of the idea and perfectly dramatic use of the island.

Similarly monumental installations include Danish artists Randi and Katrine's walk-through, pastel-fronted The Village (2014), a place where the idyllic and the parochial are in uncomfortable tension; Eva Koch's Turbine Hall-height I AM THE RIVER (2012), a video waterfall that takes on uncanny realness as you approach; Gerda Steiner and Jorg Lenzlinger's Bush Power (2014), a sprawling, chaotic gymnasium/generator of absurdist interaction; and Tori Wranes dark fairytale of a performance work, Stone and Singer (2014).

In the island's Industrial Precinct, the few more contemplative works tend to get lost, but there is room to appreciate them if you venture further to the Docks Precinct. Mikala Dwyer's ethereal-looking 'air sculptures' The Hollows (2014) create a magical, suspended moment, while Ignas Krunglevicius's Interrogation (2009) is a hypnotic deconstruction of language and the legal system that is worth losing some time in.

The whole-day-consuming Cockatoo Island is actually just one of five major venues for the festival. It is an impressive feature of the 19th Biennale of Sydney that the different venues are so clearly distinguished, each exploring different themes and mediums, evoking distinct moods and applying their own display techniques.

Carriageworks, a new venue this year, references its recent history as a film studio for George Miller's Dr D. The exhibition there is focused on video works and cinematic imagery and, with that in mind, staged in near darkness. Discovering works within this shadowy realm is a unique and memorable experience, particularly coming upon the spooky centerpiece Where Spirits Dwell (2014), Gabriel Lester's life-size shack with curtains mid-bluster.

The Art Gallery of NSW and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia play opposites for the Biennale period. Inspired by the open, waterside location, the MCA is the home of "liminal, libidinous, liquious" works (Juliana's words), while the earthy, central AGNSW is an "earth/fire space". The art at the MCA invites emotional, intuitive responses, while the AGNSW is more rational and outward-looking, housing most of the works that speak to the political issues circulating in the lead-up to the Biennale.

A highlight in the MCA space is Douglas Gordon's Phantom (2011), a seductive yet mournful video and installation work that calls on the talents and beautiful eye of singer-songwriter Rufus Wainwright. Another is Roni Horn's hefty Ten Liquid Incidents, whose solid cast glass is a trompe l'oeil, looking like a series of light, mysterious, very much fluid pools. There are so many great works to appreciate here, and playful, informative presentation to accompany them.

In the Art Gallery of NSW, concrete statements mix with more oblique ones. The act of seeking refuge, high-density housing, religious belief, the wheel of fortune and the National Apology are just some of the subjects zeroed in on. Michael Cook's photographic series Majority Rule is a powerful one, using a sole repeated figure to call plaintive attention to the marginalisation of Australia's original peoples from its current social spaces. Yhonnie Scarce's Weak in Colour But Strong in Blood (2013/14) is even more disturbing on its subject of eugenics, achieving a deep symbolism through its ambitious glasswork.

Serious art connoisseurs (and bird lovers) should head to the fifth venue, Woolloomoolloo's Artspace, where five works are showcased in an overlapping fashion. You'll have to pick your way through Ugo Rondinone's little bronze bird sculptures, each one idiosyncratic and identified by name (the sun, the horizon, the universe), to take in the ambiguous, less obviously connected works.

There is a sixth venue, of course: all around you. Just hang around inner-Sydney's public spaces and wait for something inexplicable to happen.

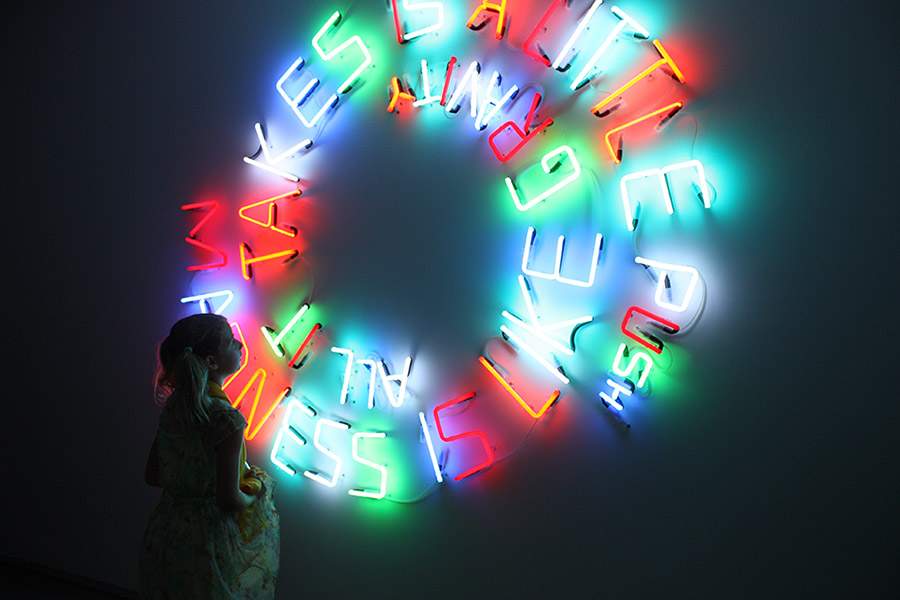

See some of the fantastic images from the Biennale in our gallery.