Taboo

It has blackface. It has porn. It has colonial-era atomisation of race into castes, with accompanying photographs.

Overview

Curator Brook Andrews’ Taboo aims to give its artists space to make art about things normally considered too unmentionable to cover. Here, taboo means mainly race, racism and colonialism. The show has blackface. The show has porn. The show has colonial-era atomisation of race into castes, with accompanying photographs. There is nudity. There are multiple references to the Belgian Congo.

There is also a real depth of talent. Probably the show’s strongest statement is Andrew’s gathering of so strong a mix of artists and art, with such apparent ease. Taboo seems to draw from a burgeoning field of artists with interesting things to say on race. A field much wider than we usually get to see in mainstream Australian galleries.

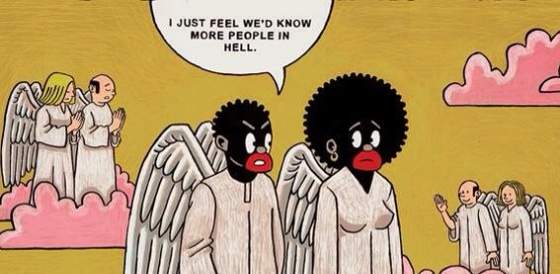

Most of the more shocking stuff is quarantined in a single room hidden to the left of the exhibition. Some mid-sized Anton Kannemeyer works are dispersed here around a long table of original news photos depicting genocide, or colonial-era ethnography, and Jompet Kuswidananto’s brilliant, motive sculpture War of Java: Do You Remember #3. Kannemeyer’s works are drawn in a Tintin in the Congo-style, veering from political commentary, to humour, to crushing, amputation references about the horror upon horror that was the Belgian Congo. Many are funny, the others quietly moving.

In the main room the art is powerful, but less confronting. Ricardo Idagi’s ceramics have rich colours and powerful eyes as he comments on race roles. Alicia Henry’s silhouetted or coffee-stained figures stare through you from a sadder, richer place. (The ones who still have eyes, anyway.) Judy Watson’s Blood, meanwhile, cleverly arranges apparently ethnographic blood samples of gallery staff. The samples are laid out dispassionately, seeming to study the sampling process itself. Labels read "collector", "artist", "curator", "archivist".

Despite the quality of the art on show, none of the pieces are presented with title cards, or any real labelling context beside them. This isn’t in itself a bad thing, and certainly ups their striking artistic value for those already in the know. But for people not already familiar with the topics and past horrors at hand it becomes harder to penetrate and leaves the casual viewer with nowhere to go with their (no-doubt) newly-found indignation.

Nonetheless, on the date visited, the exhibition was crowded with patient visitors. And it’s an exhibition that merits that sort of attention. It’s not, mostly, a fun exhibition. But despite reservations about its presentation, there is some powerful art on display.

Image: Anton Kannemeyer, In Heaven 2011. Courtesy the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg © the artist