Tehching Hsieh: One Year Performance (Time Clock Piece)

Marina Abramovic calls him a 'master' of live art, and it's probably because of this endurance piece.

Overview

"I don't think that art can change the world. But at least art can help us to unveil life," says Tehching Hsieh in conversation with academic Adrian Heathfield. This unveiling of life is imperative to Hsieh's performance art; he collapses the distinction between art and life in a way that is profound, pioneering and uncompromising.

In 1974, Hsieh arrived in New York City. Using the name 'Sam' to mask his illegal immigrant status, he abandoned painting and began exploring durational performance art. This involved embarking on five one-year-long works, unprecedented in their physical and psychological exertion.

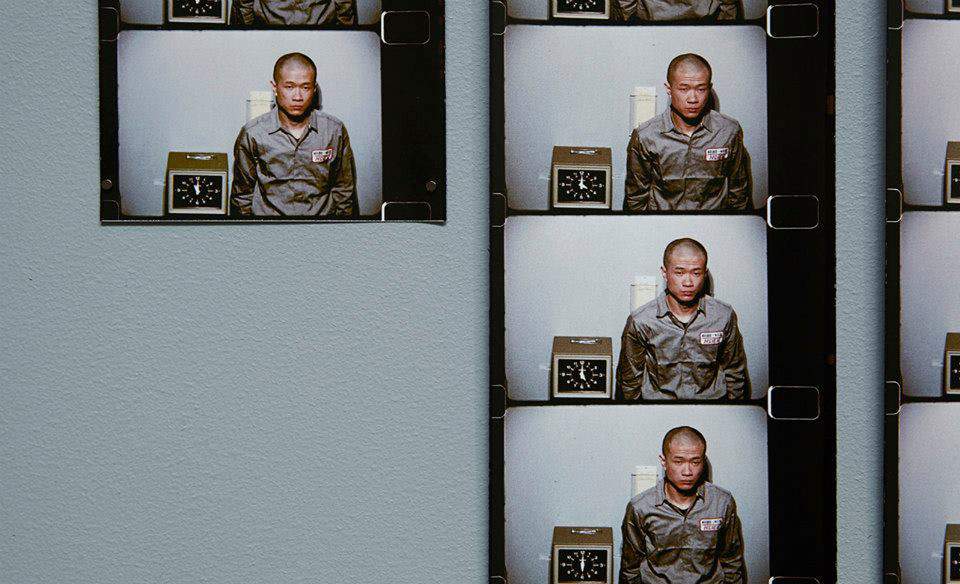

Carriageworks presents Hsieh's debut solo exhibition in Australia: a rigorous documentation of One Year Performance 1980-1980 (Time Clock Piece). For this work, he punched a time card, once an hour, every hour, for an entire year.

The installation consists of the grey uniform he wore, witness testimonies, an artist statement, the time clock, 366 time-cards, 8,621 photographs of himself punching the time clock, and perhaps what is most affecting, a 16mm film crunching the year-long experience into a gruelling six minutes — during which time, hair sprouts from his shaven head, growing to his shoulders.

Intuitively, many read this work as a critique of industrial labour and exploitation. Hsieh embodies the alienated worker, tethered to a relentless, repetitive action. Yet, he is not creating a product to be consumed in a conventional sense, in his own words, he is "working hard to waste time". However, Hsieh insists that although his work fits into a political framework, he is not a political artist. His quest is more philosophical, investigating the universal aspects of being. In a way, the idea of 'punching time' is akin to killing time — a way of dealing with its constancy and absurdity.

The methodical grid of 'mug-shots' wallpapering the space induces a feeling of claustrophobia. Over a prolonged time period, the execution of a simple instruction becomes a momentous task. Yet it's difficult to spot cracks of frustration or unrest in Hsieh's physical appearance. He is remarkably disciplined in the way he makes and documents his art, striving forward with self-punishing dedication.

There are only very subtle details that individuate the photographs, as he presents the same resolute expression and stands in the same position. Also, Hsieh's artist statements could almost be legal contracts. They clearly outline each step of the project, committing him for the stipulated time period. In saying this, there were a number of occasions where Hsieh failed to punch the time card. However, these elements of failure seem to humanise the work. Like reporting an absence, he scrupulously documents the reasons for these failures.

From working as an unfunded and illegal artist, Hsieh is now a seminal figure in the world of performance art. In recent years there has been a critical reappraisal of his work, with exhibitions at MoMA and the Guggenheim. Encircled by these hourly portraits, it's difficult not to be impressed by Hsieh's iron-clad determination. This is one work in an oeuvre of physical extremity and conceptual purity.

Hsieh made out list of ten crazy things people have done in the name of live art. Check out the other nine.

Image: Zan Wimberley.