Thyestes – Belvoir and The Hayloft Project

'After Seneca'. A long way after.

Overview

Sleeping with your mother. Killing your father. Eating your children. Usurping your brother. Greek theatre is full of the kinds of extreme acts of violence and wrongness that we may enjoy watching but don't often see as tied to our own world. That all changes when the Hayloft Project take the Greek tragedy that birthed all other Greek tragedies, Thyestes, and mine it for rich veins of the modern and the real.

This production already comes on the back of a wave of approval — from Melbourne theatregoers, who raved about it; from Belvoir, who afterwards recruited director Simon Stone to come to Sydney and make shows for us, to wit, The Wild Duck, Neighbourhood Watch and STC's Baal — and this review, sadly for contrarians, just can't find a voice of dissent. Thyestes is brilliant, a true shock and a thrill to watch.

The story of Thyestes, once by Seneca, is brutal even among its contemporaries. After killing their half-brother and triggering the suicide of their mother, brothers Thyestes and Atreus are meant to be sharing rule of Mycenae but instead vie for total control. Eventually, Atreus, out for vengeance, murders Thyestes' sons and, yes, feeds them to him as part of a feast (spaghetti and meatballs will not be appetising again for a long time). Things do not improve from here. An oracle tells Thyestes that a child by his own daughter Pelopia will one day kill Atreus, and eventually, after many more tragedies, this does come to pass.

It pays to learn the synopsis, for this production of Thyestes takes place around it rather than within it. It spends time in the set-ups to murders, the domestic lives that breed adultery, and the conversations over that dinner table. It might seem counter to the contemporary impulse to skirt the prime moments of brutality, but in doing so, this Thyestes finds a beautifully uneasy tension between overt violence, covert violence and nice chitchat that always threatens to spoil. The first scene, for instance, is an oddly charming buddy comedy as three brothers discuss naïve gestures of love, watching Water Rats dubbed into Spanish, wanting to sleep with the 'middle sister' from Hanson, and, um, being penetrated with a strap-on. When it ends, with the impending shooting of the innocent and unaware Chryssipus (Ryan), you dread that it will be him that goes. Plus, there's still blood, nudity and oral sex to spare.

If the Hayloft Project are looking for modern manifestations of the extreme behaviours that seem to have infected the ancients, they find it in the tyranny of Atreus (played with sick glee by Mark Winter). The character is a charismatic egomaniac who needs attention like oxygen, gets off on controlling everyone around him and commands followers. Very plausible. Getting power, it turns out, doesn't make him nicer. He's terrifying. It's nice to think that he does sort of get his comeuppance, but that isn't the moral of the story.

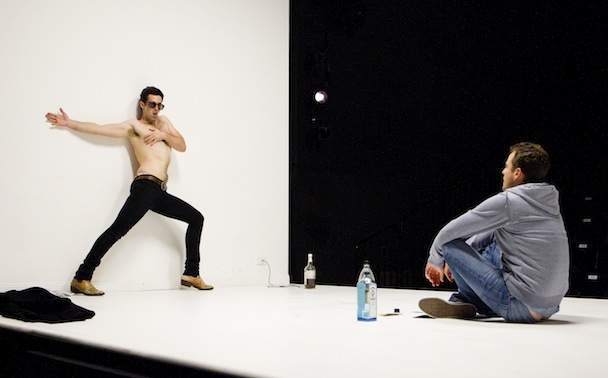

The stage design (by Claude Marcos), meanwhile, is a wonder. Its minimalist yet spectacular white cube creates an illusion of containment that is constantly broken by sweeping scene changes, and it also starts an interesting game of seeing how unconventional audience placement can affect experience.

In the emerging Stone oeuvre, this is still the most cohesive and clear of vision and purpose. Which is unexpected given the production's anarchic veneer. It's testament to the power of an exceptional group of long-term collaborators: Stone, Winter and co-writers/performers Chris Ryan and Thomas Henning devised this script together and continued to rip out and replace scenes well into the Melbourne season. May they dismember and reanimate many classics to come.