Sundown

Tim Roth plays a wealthy British man seeking a permanent escape in Acapulco in this contemplative, bleak and gripping film.

Overview

In Sundown's holiday porn-style opening scenes, a clearly wealthy British family enjoys the most indulgent kind of Acapulco getaway that anyone possibly can. Beneath the blazing blue Mexican sky, at a resort that visibly costs a pretty penny, Alice Bennett (Charlotte Gainsbourg, The Snowman), her brother Neil (Tim Roth, Bergman Island), and her teenage children Alexa (Albertine Kotting McMillan, A Very British Scandal) and Colin (Samuel Bottomley, Everybody's Talking About Jamie) swim and lounge and sip, with margaritas, massages and moneyed bliss flowing freely. For many, it'd be a dream vacation. For Alice and her kids, it's routine, but they're still enjoying themselves. The look on Neil's passive face says everything, however. It's the picture of apathy — even though, as the film soon shows, he flat-out refuses to be anywhere else.

The last time that a Michel Franco-written and -directed movie reached screens, it came courtesy of the Mexican filmmaker's savage class warfare drama New Order, which didn't hold back in ripping into the vast chasm between the ridiculously rich and everyone else. Sundown is equally as brutal, but it isn't quite Franco's take on The White Lotus or Nine Perfect Strangers, either. Rather, it's primarily a slippery and sinewy character study about a man with everything as well as nothing. Much happens within the feature's brief 82-minute running time. Slowly, enough is unveiled about the Bennett family's background, and why their extravagant jaunt abroad couldn't be a more ordinary event in their lavish lives. Still, that indifferent expression adorning Neil's dial rarely falters, whether grief, violence, trauma, lust, love, wins or losses cast a shadow over or brighten up his poolside and seaside stints knocking back drinks in the sunshine.

For anyone else, the first interruption that comes the Bennetts' way would change this trip forever; indeed, for Alice, Alexa and Colin, it does instantly. Thanks to one sudden phone call, Alice learns that her mother is gravely ill. Via another while the quartet is hightailing it to the airport, she discovers that the worst has occurred. Viewers can be forgiven for initially thinking that Neil is her cruelly uncaring husband in these moments — Franco doesn't spell out their relationship until later, and Neil doesn't act for a second like someone who might and then does lose his mum. Before boarding the plane home, he shows the faintest glimmer of emotion when he announces that he's forgotten his passport, though. That said, he isn't agitated about delaying his journey back, but about the possibility that his relatives mightn't jet off and leave him alone.

Sundown is often a restrained film, intentionally so. It doles out the reasons behind Neil's behaviour, and even basic explanatory information, as miserly as its protagonist cracks a smile. The movie itself is eventually a tad more forthcoming than Neil, but it remains firmly steeped in Franco's usual mindset: life happens, contentedly and grimly alike, and we're all just weathering it. Neither the highs nor lows appear to bother Neil, who holes up at the first hotel his cab driver takes him to, then starts making excuses and simply ignoring Alice's worried calls and texts. He navigates an affair with the younger Berenice (Iazua Larios, Ricochet) as well, and carries on like he doesn't have a care in the world. His sister returns, frantic and angry, but even then he's nonplussed. The same proves true, too, when a gangland execution bloodies his leisurely days by the beach, and also when violence cuts far closer to home.

Tranquility, bleakness, the ordinary and the extreme in-between: it all keeps coming throughout Sundown. Yes, life keeps happening, even amid the relaxed air that breezes through the movie's aforementioned introductory moments. When there's little on the Bennetts' minds except unwinding, their comfort literally comes at the hands of Acapulco's workers. In the streets, an incendiary mood bubbles well before bodies end up on the sand. The gap between the one percent and the rest of us always stays in plain sight. The fact that a getaway as luxe as this one relies upon not the kindness but the exhaustive labour of others never slinks away. Also, that Neil's family wealth springs from slaughter isn't subtle — animals, in the pork trade — but that's never been Franco's approach. Still, Sundown is a film to soak up, riding its twists and wading through its questions, including the plethora that keep springing about Neil's actions.

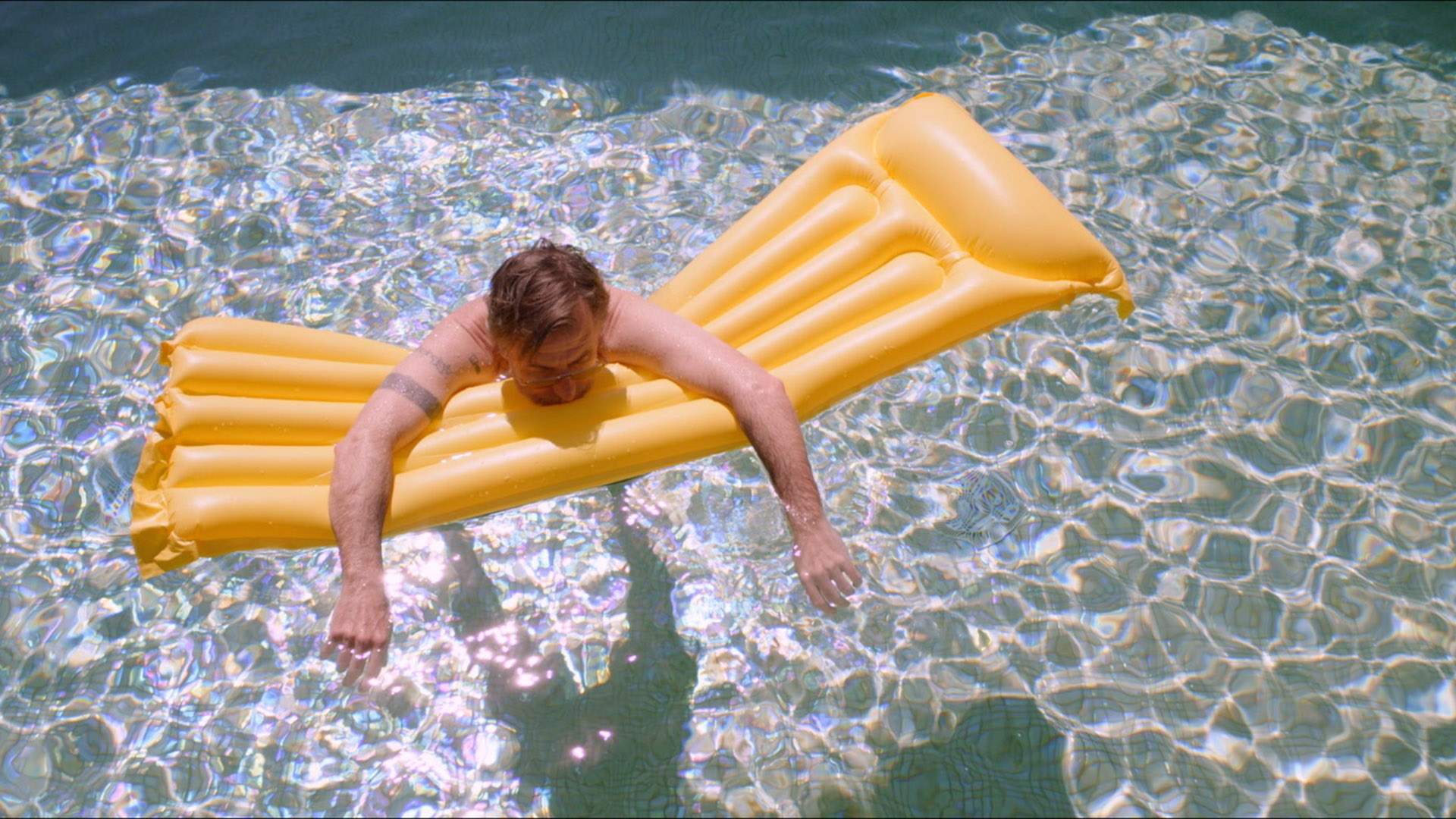

The last time that Roth worked with Franco, in 2015's Chronic, he turned in a mesmerising performance. Here, he's magnetic and absorbing as a man adrift by choice, through entitlement and also due to the cards he's been dealt. Some shots play up that idea with the director's characteristic lack of understatement — floating in a pool, for instance — but the point would've been plain via the film's central performance alone. Roth isn't coasting, or bobbing, or doing anything aimlessly. Sundown's audience can see Neil's behaviour as comic, heartless, troubled or arrogant, or a combination of all four and more, but Roth makes the sense of detachment and entropy behind the character's every move echo from the screen. His efforts prove all the more stark against the also-wonderful Gainsbourg, in a far smaller part. Unsurprisingly, Alice is anything but dispassionate, with her brother's subterfuge, selfishness and utter lack of care for everyone he's affecting earning her increasing exasperation.

For Franco, forgoing nuance means staring head-on at the tales he's telling, the people within them and the statements about humanity that are being made — and Belgian cinematographer Yves Cape, who has a number of the filmmaker's pictures to his name (plus entrancing 2019 French film Zombi Child as well), eagerly obliges. Roving your eyes over Sundown's patient frames is an exercise in careful observation, sometimes peering so closely that you can almost count Roth's pores, but usually with a sense of distance that mirrors the space that Neil cultivates around himself. Watching this ruminative feature also requires confronting existential woes — and pondering existence — both compellingly and unsettlingly so. Franco has never had any fondness for privilege, or much for human nature; with his latest penetrating film, he's as unforgiving as always, but also as committed to unpacking what it means to define your own path.