How Photography in Australia Got from Gilded Copper to Ubiquitous Selfies

Given the effects of extreme heat, it's remarkable we took any photos at all.

In partnership with

From heavy equipment to smart phones, darkrooms to USB sticks and hour-long to instantaneous exposure, photography has come a long way in a few short centuries. The Photograph and Australia at the Art Gallery of NSW traces the origins of photography in this country.

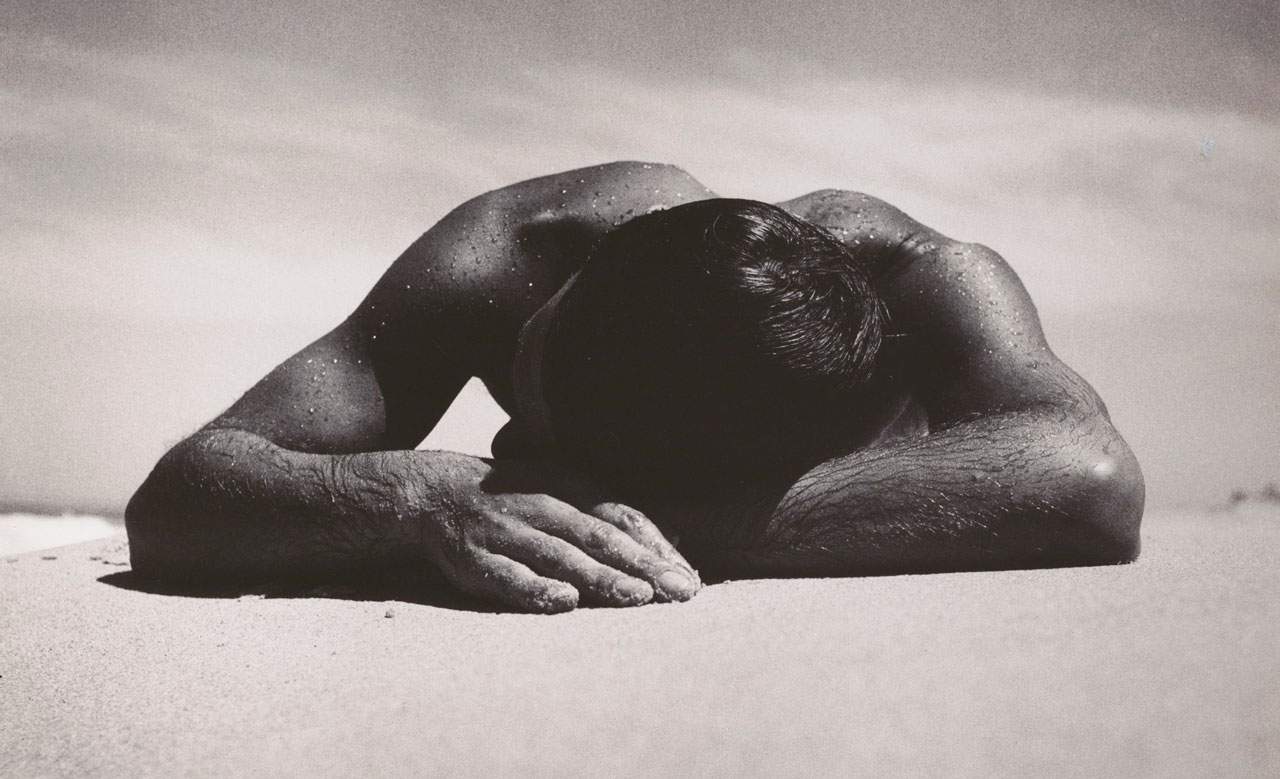

Parallel to the evolution of photographic technology is the story of a burgeoning national identity. The exhibition features iconic images such as Max Dupain’s bronzed Sunbaker and Mervyn Bishop’s photograph of the symbolic soil pour from Gough Whitlam to Vincent Lingiari in 1975. From documentary to conceptual photography, curator Judy Annear has dug up a vast collection of work from amateurs, artists, explorers and enthusiasts. “People know about Olive Cotton, Max Dupain and David Moore, but those artists make up a very narrow band from about the 1930s to '70s,” she says.

Once restricted to specialists and aristocrats, photography as a medium has been democratised over the years, and that's reflected in the exhibition. “Now photography is ubiquitous, it has changed our entire social fabric,” says Annear. “Most of the time images become recognisable not because they have some local flavour but simply because of the confluence between popular media and chance.”

PRIVATE MADE PUBLIC: THE DAGUERREOTYPE

One section of the show pays homage to the daguerreotype. One of the first types of photographs made popular, it was developed without the use of a negative and printed on a polished sheet of silver-coated copper. The daguerreotype camera came in a range of shapes and sizes, though it typically resembled a wooden box.

The tiny images featured from this era are cased in gilded frames and velvet covers. Looking at these little relics of intimacy, there are many unknown photographers and subjects. “I have to say, this is the hardest show of my entire career,” says Annear. “We all want stories to be nice and neat, but it’s like looking at your own family’s photo album; it never turns out the way you want. The whole thing is full of question marks.”

One of the striking characteristics of the show is the way Annear pairs together contemporary and traditional photography. “I think the exhibition offered a unique opportunity in terms of the technology and what was happening here in Australia; you do see things growing up and you do see adaptation,” she says. For example, the way Tracy Moffatt’s Warhol-inspired Beauties has been positioned suggests a reworking of the daguerreotype. Three photographs of an Indigenous stockman have been dipped in tints of cream, mulberry and wine, mirroring early attempts to integrate colour into the production process.

Image: Unknown photographer, Isabella Carfrae on horseback, Ledcourt, Stawell, Victoria c1855.

THE PROFESSIONAL PHOTOGRAPHER: OUT OF EUROPE AND INTO THE BUSH

Taking photographs of people was one thing, but the practical challenges of venturing into the harsh Australian climate was quite another. The period from about 1850 – 1860 witnessed the birth of the professional photographer. However, the extreme heat made the process of taking and developing photographs very difficult and often required a portable or makeshift darkroom.

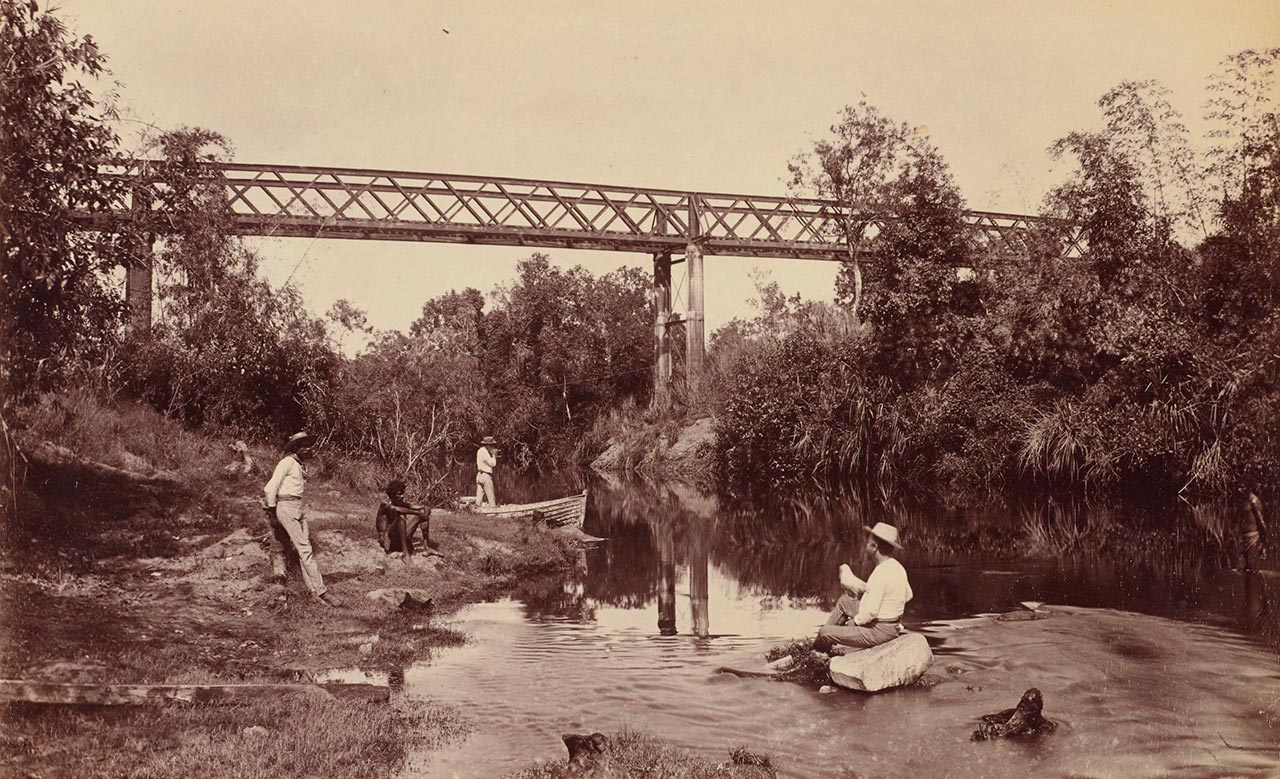

“The colonisers were working out how to make photographs at the same time as they were working out how to grapple with the Australian environment and build towns,” says Annear. “That’s why the nineteenth century is such a strong part of the show.”

"At the same time, the Indigenous people were trying to adapt to colonisation, since colonisation is never pretty," she says. The centrality of colonialism can be seen in the early ethnographic portraiture of Paul Foelsche and JW Lindt. The stilted quality of these images shows a romanticised version of Indigenous life. Complete with theatrical sets and costumes, the subjects are manipulated into artificial positions. While spontaneity is so easy to capture nowadays, these portraits are the product of painstakingly long sittings.

Image: Paul Foelsche, Adelaide River (1887)

THE TWENTIETH CENTURY AND THE RISE OF EVERYDAY LIFE

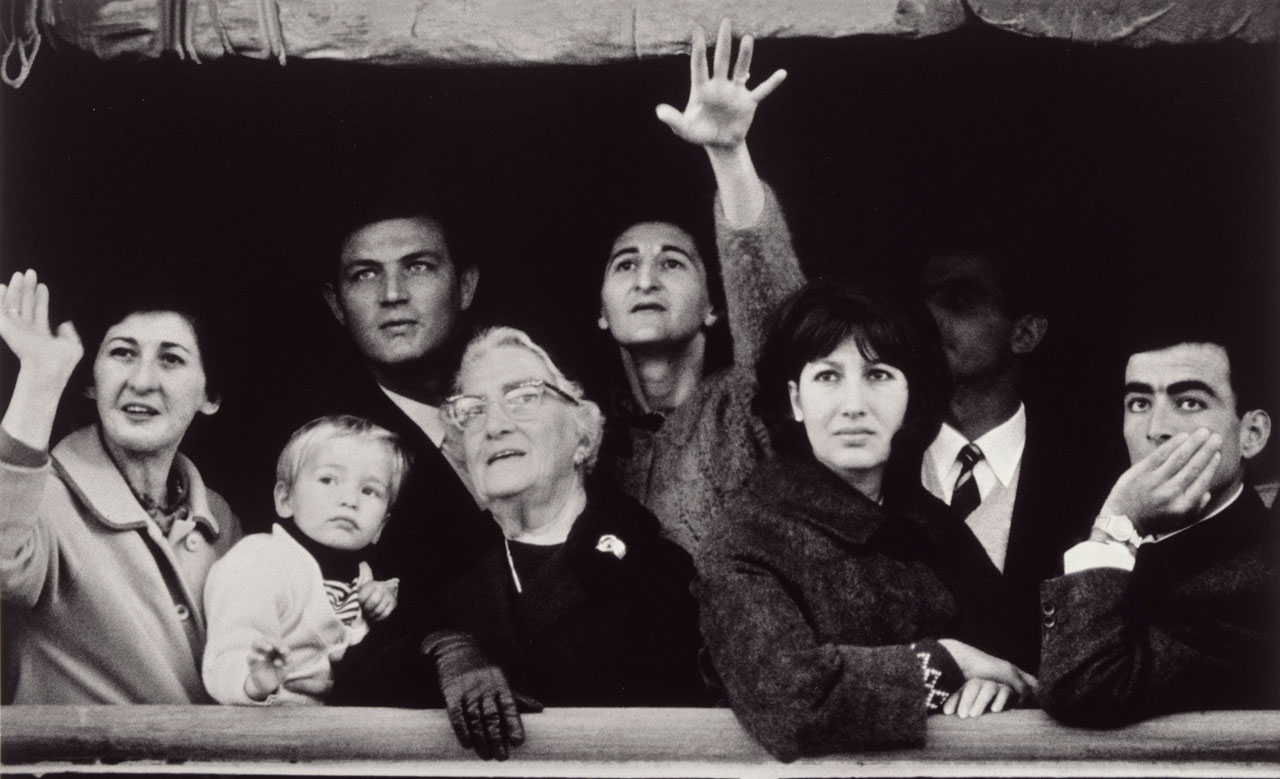

Prior to colour photography, images were touched up with oil paints or tinted with a single colour. From the '60s onward, the explosion of alternative lifestyles led to more recognition of amateur and conceptual photography. An easier process of reproduction meant a greater number of photographers. And importantly, the Single Lens Reflex (SLR) camera grew more sophisticated. Artists began to draw links to Australia’s migrant roots, Indigenous heritage and powerful women. In particular, the self-portrait became a vehicle for feminism in Australia, with artists such as Sue Ford and Carol Jones sharing snippets of their personal lives.

Although these images have less of an artificial character, Annear maintains that “there are at least two modes of constructing a photograph. There’s what was going on at the time and what we bring to it. We bring a lot to photography because we want it to be real. And it is so close to reality but it’s not, it’s just a piece of paper or something on a screen.”

Image: David Moore, Migrants arriving in Sydney (1966)

DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHY: PUTTING THINGS IN PERSPECTIVE

Often it can feel like 21st-century technology has no limits. Constantly connected to the web on a handful of different devices, we have instantaneous access to a whole world of images. The prowess of digital photography is showcased through the work of Simryn Gill and her aerial photographs of open-cut mines, exposing the geological history of Australia. It is particularly interesting to compare these vast holes in the earth to the bustling towns and erection of skyscrapers during the late 19th and early 20th century.

Reflecting on this history, the transformation of photographic technology and what it can capture has had a profound effect on how we experience time. For instance, there is the duration of an exposure, the working life of an artist, the age of our continent and the time it takes to upload a photo, to name a few. “With this exhibition, I wanted people consider that we are in the present looking at the past and it is a highly speculative, partial story,” says Annear. “It’s a complex story but at the same time you need to let your imagination roam a bit. It’s not an easy story – there’s no straightforward chronology.”

Image: Simryn Gill, Eyes and Storms #13 (2012), Art Gallery of NSW.

The Photograph and Australia is showing at the Art Gallery of New South Wales until June 8, 2015.

Top image: Max Dupain, Sunbaker (1937).