Sharing a Searing Gillian Anderson-Starring Production of a Stage Masterpiece: Benedict Andrews Talks NT Live's 'A Streetcar Named Desire'

This Australian playwright and director's UK theatre version of one of America's most-stunning plays was first performed in 2014 — and it keeps returning to cinemas.

Stunning art always endures, as A Streetcar Named Desire has for nearing eight decades now. Tennessee Williams' tale of Southern belle Blanche DuBois, her sister Stella and the latter's husband Stanley Kowalski first premiered via a Broadway production starring Jessica Tandy, Kim Hunter and Marlon Brando, and has repeatedly returned to stages since. Indeed, this southern-gothic heartbreaker has trodden the boards worldwide with everyone from Glenn Close (Black in Action), Cate Blanchett (Black Bag) and Frances McDormand (Women Talking) to John C Reilly (Winning Time: The Rise of the Lakers Dynasty), Joel Edgerton (Dark Matter) and Paul Mescal (Paul Mescal) in its cast. Four Oscars also came the way of Elia Kazan's 1951 film, where he adapted the play that he'd directed in theatres into a screen classic with much of its originating stage cast.

Spectacular theatre can make that leap to screens — but the stage productions themselves have historically only lived on via memory and reputation. No matter how immersive and exceptional, and how urgent and unforgettable as well, theatre performances are live and therefore fleeting. They're tied to a specific place and usually solely experienced in the moment. NT Live did its part to help change that over 15 years ago, when it began filming National Theatre productions in the United Kingdom — expanding to other companies, too — then beaming everything from new Shakespearean stagings and Danny Boyle's (28 Years Later) take on Frankenstein to Fleabag and The Importance of Being Earnest into cinemas globally.

In 2014 when he unleashed his Gillian Anderson (The Salt Path)-, Ben Foster (Long Day's Journey Into Night)- and Vanessa Kirby (Napoleon)-starring version of A Streetcar Named Desire at The Young Vic in London, Australian playwright, stage and opera director, and filmmaker Benedict Andrews was well-aware that he was taking on a classic, a masterpiece, and a play that ranks among the 20th century's best and has burned itself into memories. He'd done so before at the Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz in Berlin. He didn't initially know, though, that he'd be joining the NT Live ranks, that audiences worldwide would be able to catch it on the big screen, and that they'd still be watching 11 years later. In Australia, Andrews' Streetcar returned to cinemas from Thursday, June 19, 2025.

"The play is very dear to my heart, but the nature of theatre is usually that it's ephemeral," he tells Concrete Playground. "Theatre's usually ephemeral and that is its beauty — that it usually just exists in this brief compact with the audience and the viewer when the play comes to life nightly. So it's weird that it's released in cinemas again. It's great though — because I found during COVID, they re-released it for free online at some point, and it found a whole new generation of viewers," the Australian continues. "Not just people who didn't live in London or New York, so couldn't see it there, but I'm having conversations with people in in really far-flung and diverse places, and maybe of a different generation who are seeing it, and discovering the play for the first time through that production."

"I've had people tell me that — like a young actress tell me that seeing this production when she was in high school made her want to become an actress. So it's great it's out in the world again, and on cinema screens."

Gareth Cattermole/Getty Images for BFI.

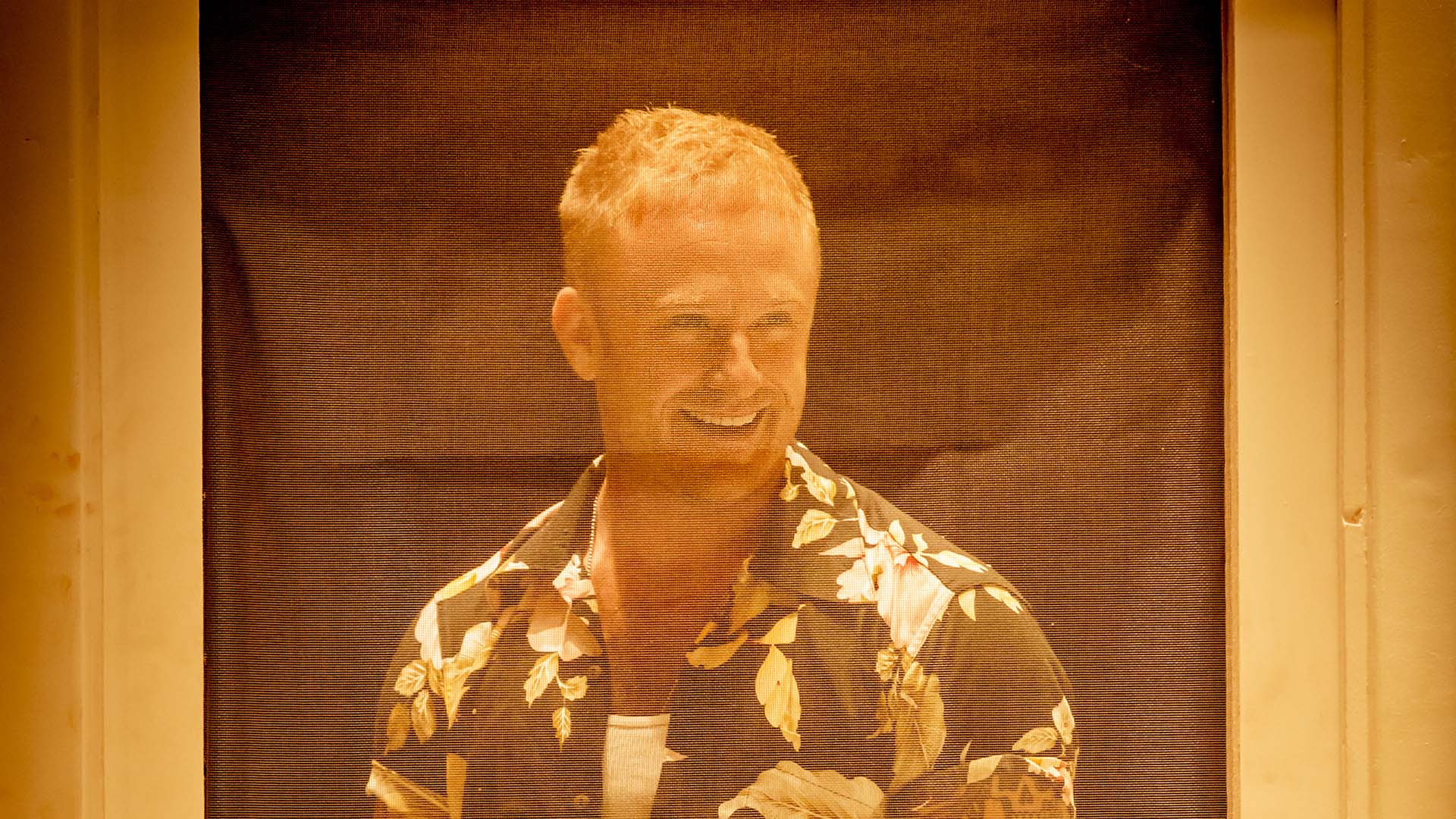

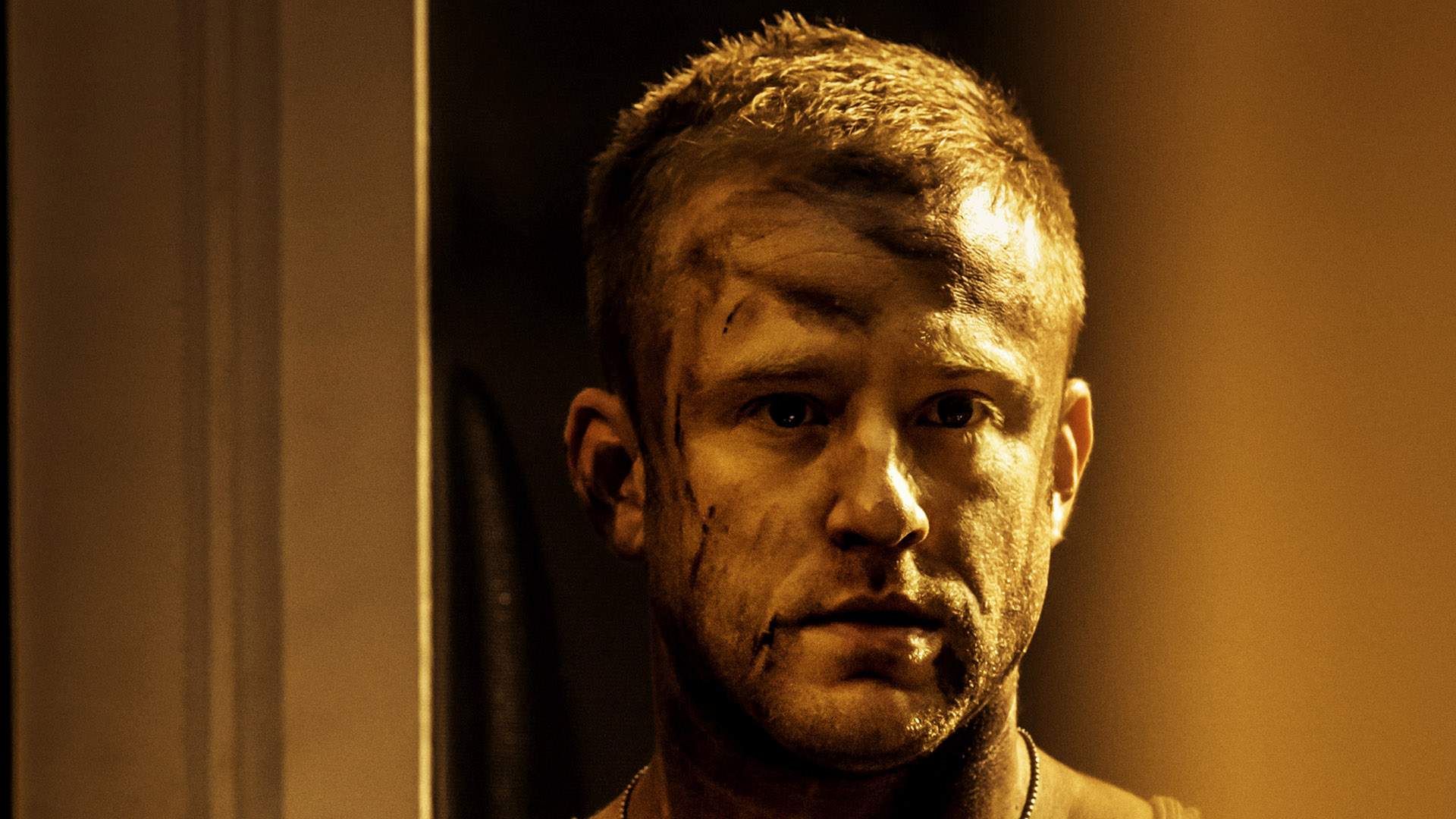

Complicated relationships, desire, raw emotions that can't be contained: these themes have recurred in Andrews' work. They all scorch and sear as Blanche's once well-to-do life keeps shattering, leading her to take the titular transport to Stella and Stanley's two-room New Orleans apartment, and to the toxicity — verbally, emotionally, psychologically and physically — of being in her brother-in-law's orbit. If you'd like to think of the trio's altercations, and those involving Stanley's friend and Blanche's hoped-for beau Mitch (Corey Johnson, September 5), as a traumatic merry-go-round, Andrews has taken that idea literally in this staging. Tying into Blanche's alcoholism and downward spiral, this aesthetically striking production is both in the round and revolves, the skeleton of the Kowalskis' powderkeg of a flat exposed to theatregoers as the show constantly rotates.

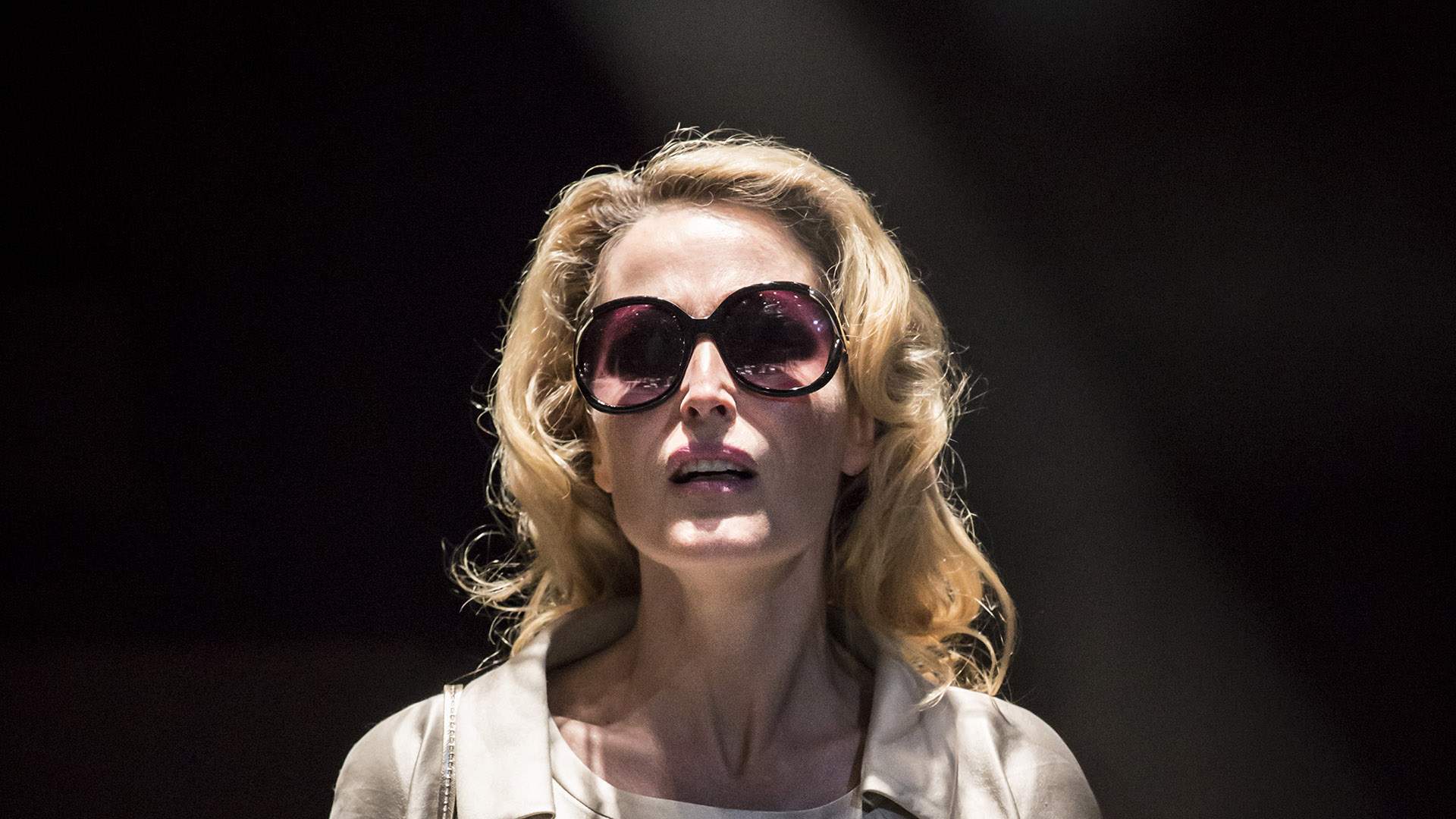

Sculptural sets, spaces that actors are required to interact with rather than just stand upon, are equally a regular element in Andrews' stage creations. See also: his Cat on a Hot Tin Roof in 2017, another dance with a Williams great for The Young Vic that was also immortalised by NT Live. Streetcar's iteration is arresting, but that label perhaps best applies to Anderson as its Blanche — a part that she'd been wanting to step into since she was 16. While she'll always be The X-Files' Agent Dana Scully, The Fall's DSU Stella Gibson and Sex Education's Jean Milburn, among the immense range of roles before and after always relying on the kindness of strangers, Anderson's portrayal here is one that you'll always remember her for as much as the above once you've seen it.

2026 will be three decades since Andrews kicked off his career as a theatre director with Wounds to the Face and Storm From Paradise in Adelaide. From the South Australian capital, he went to Sydney Theatre Company, Belvoir and Malthouse Theatre — and to London's stages, New York's as well with both A Streetcar Named Desire and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and also Munich, Berlin, Reykjavik, Copenhagen, Buenos Aires, Amsterdam, Frankfurt and more. Opera beckoned. On the big screen, he was behind 2016's stage-to-screen adaptation of Blackbird as the Rooney Mara (La Cocina)- and Ben Mendelsohn (Andor)-starring Una, then 2018's Kristen Stewart (Love Lies Bleeding)-led Seberg. Alongside digging into his Streetcar journey, including whether thinking about the cinema experience is part of directing a stage production that will be filmed and then show in cinemas, Anderson's stellar work, and ensuring that the play's themes and emotions are always bubbling, we also explored his path to here with Andrews in our in-depth discussion.

On Whether the Possibility of a Stage Production Being Filmed for the Big Screen Changes Anything About Andrews' Approach

"No, no, no, never. In the case of Streetcar, I didn't know. I guess NT Live branching out of the National Theatre stuff, because this was a Young Vic production, was fairly uncommon at the time.

I've had two productions filmed, I think, only — which have both been Tennessee Williams. They also filmed the Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. And no, I don't and probably I wouldn't at all.

Well, I've had a bunch of operas films since as well — and I never think about it. When I've worked with the team on it, I talked to them about it like they're filming a boxing match or a football game. So we discussed what their setup would be, and with them having watched the production. Obviously Streetcar is very special because of the revolving stage, and what that means to try to shoot that or capture that, but I discuss it with them more like they're going in to shoot that, to capture the live experience of it.

Rather than, because I'm also a filmmaker, rather than thinking about this filmmaking, I see it as much more of almost a functional recording that they happen to do very well — like if you watch boxing at the Olympics or you watch a well-filmed AFL game, you want it to capture the highlights and the moments, and give you the enhanced sense of being there. I think I'm trying to do that.

So then, when I'm in the rehearsal room, no, I'm not thinking about that at all. I often, when I'm in a rehearsal room, I give myself and the actors very fundamental challenges to work with and overcome. And those challenges, I think, are about — they're like a kind of drill to drill very deeply into the core of the play. Rather than just assuming we can access that play by selling this kind of difficulty, I think then it allows you to access the raw matter of the play in a new and immediate way.

So the revolve in the Streetcar production was exactly that. I felt it was the perfect metaphor for the play. It begins when she takes this schluck of alcohol. It reflects her addiction and the sense of what it means to be in her downward spiral with her.

But it also is very visceral. Every single audience member gets a different perspective on what's happening in that room, as it constantly — the in-the-theatre experience of it — moves in and out of long shot and closeup, and literally every seat is seeing a different way into this cage where this encounter is going on between Blanche and Stanley.

And we had that on throughout rehearsals. It's not some big decorative thing that's put on at the end. If it's going to be this drill, we have to learn to work with it. And the effect of it was so disorientating that the actors would go home and the room would be spinning. And I remember my apartment in London spinning when I went back after being it on all day. I think they would to take motion-sickness tablets, and so on.

Beyond that, it's just also: how do you use it? What does it mean to be on and off it? And all that.

So when you're so busy with the play and busy with helping the actors unlock it and find its raw heart, which all of them do, but particularly the four, the quartet, of Blanche and Stella and Stanley and Mitch, there's so much to be busy with in that that I'm not thinking about that.

But in a similar way, I'm not really thinking about the audience, even the theatre audience, when I'm making something — until I'm in previews. I'm sort of the first audience, and the other people in the room are the tuning rod through which the players get to charge through. And then you hope you get that to such a point of intensity and feeling that then it's ready to share with a larger body of people."

On How Staging a Play on a Revolving Set Gives Every Audience Member a Different Immersive Experience

"I'm constantly thinking about that. And part of this is the acceptance that you cannot control that it will not be the same for everybody.

To take the football analogy again, if you're sitting behind the white sticks at one end, you're seeing a different game from somebody sitting in the centre line, except then that it's moving, so you're rotating that perspective. But you have to accept that no audience member will literally ever get the same view of the show, so that even if audience member X bought exactly the same seat two nights in a row, just because of the slight variation in the motion of that thing, they're going to — maybe on a certain line, Blanche is going to be on the side angle one night, and on the next, she's going to be momentarily obscured by the shower curtain coming past.

But that was part of it — that enhanced voyeurism of that, but it's like an active voyeurism, like you're aware that you're watching this fight in this cage, but also this very, very painful to watch, at-times unraveling and madness, this coming apart, of this woman and this family, and the sexual violence when that begins. But I think it meant that the audience had to really lean in and be complicit with it.

So to answer your question, I'm thinking about the overall implications of that. Like if I was making a static picture from the front, that works — actually, that changes, the static picture changes from the position, the ideal centre-perspective position where the king used to sit, it actually changes as you move further away and the perspective disintegrates. So there's sort of something radical and democratic in how people watch it. That cinematic effect of the wipes, and that you would each see different perspectives — but in the end, everybody united in the same moment.

That's what I think is also really interesting. I think about it in the moment, when the Cat Power song plays at the end, when she walks out — one of the most-extraordinary moments in 20th-century theatre, this speech when she talks about, she's so broken after the rape and after knowing she's being evicted and her psyche can't cope with it anymore, but to cope with that she invents this beautiful fantasy of this man feeding her a grape on a on a boat. And she, her genius is that she invents this, and Tennessee Williams' genius at this most-broken moment, she invents and becomes the perfect actor, playing this dignified role of this woman going to meet her gentleman caller. When we know, and probably she does, that it's the doctor and nurse coming to take her to the mental asylum, which is just going to be fucking hell. A woman like that does not belong in a place like that. It's completely heartbreaking.

But the apotheosis when she invents this character, and walks out with such grace and dignity — and then in our production, where Gillian does that circle, that last circle to the Cat Power song, I think for the audience, having watched just this truly extraordinary thing that she goes through, the gift and self-sacrifice, nightly self-sacrifice of Gillian's performance, at that moment, the entire audience is just completely gathered and at one. So I think there's something about having fractured that perspective, then feeling them come together at that moment of apotheosis.

I think you're always thinking about that, how to activate that, whatever then the device you're using is. It's a bit of a similar thing in The Cherry Orchard that I just recently staged, where there's also an audience all the way around. But the actors don't have fixed positions. They change what they're doing nightly. So again, the show is constantly evolving and changing and organic, but at the same time, directorially it's still very tightly held.

Even if I'm fracturing that viewpoint in Streetcar between all these different viewpoints, I want, ideally, every viewpoint to be perfect — the perfect frame at every moment."

On Casting Gillian Anderson in a Role That She'd Wanted to Play Since She Was a Teenager — and Giving Her Another Iconic Part That She'll Always Be Remembered For

"This was my second time staging it. I staged it at the Schaubühne in Berlin a couple of years before, in German, and I always wanted to have another crack at it. And weirdly enough, that production of Streetcar was seen by David Lan, the then-Artistic Director of The Young Vic, where we staged Streetcar.

And from that, he invited me to come and work in London — and I did first an opera for him, and then a production of Chekhov's Three Sisters, which also had Vanessa Kirby in it as Masha. And Gillian saw that, and said to David 'I want him to direct me in Streetcar'. So when we met to talk about that, she told me how she'd always been thinking about Blanche and always knew she wanted to play Blanche, and I could sense that profound hunger in her to do that.

And I already had the plan in my skin. They're wildly different productions. We had a revolve in that, actually, but they're wildly different productions. But it was interesting to have that as a framework — so the first one was like sort of a rough sketch, and then the second one was much more elaborate.

So it was just a beautiful kind of confluence of me feeling very close to the play — really, really hungry to do it in English — and then finding, for me, the perfect actress for it at exactly the right time in her life to want to do it.

And it was a process and then a production just full of enormous trust and risk. I think from our very first meeting, we felt that we had found each other. I knew she trusted me to take her somewhere. And I knew she wanted to be taken somewhere.

I think she and we are very, very, very, very faithful to the play, but even in the UK at that period, at that time, even doing a non-period production of a classic that didn't look like all the other previous productions and all that — she also clearly had an appetite to be in a contemporary production.

I guess one thing I try, if I'm approaching a classical play, is to treat it as if it might be a contemporary play. And if I'm approaching a contemporary play, I treat it as if it should be a classical play and will be a classical play. And she clearly believed that there was no attempt to turn, to drag, the play or the production a safe place. She had, as I said, an enormous appetite for risk.

And you can see in the performance. So I think why it's memorable, as you say, is she puts herself on the line in every single performance. She's talked about that a lot, I gather, since — what that meant. And I think particularly when we were in New York, what that was like to get under Blanche's skin every night.

She's also talked about it, so I won't. But also, she's talked about a kind of confronting or accessing her own history of addiction in the role. And to really do Blanche, I think that is important, because it is the story of someone who is addicted to alcohol and addicted to sex, and trying to deal with the legacy and the brokenness of her own family and her own history through that."

On Ensuring That A Streetcar Named Desire's Senses of Guilt and Sadness Is Always Bubbling, and Its Volatility as Well, Alongside Its Exploration of Compulsiveness and Addiction

"I think ultimately that's about trusting the players. As such a loaded masterpiece, it is — every single moment of the play, he found such an extraordinary collision of these, of Blanche and Stanley. And I think two sides of himself, Tennessee Williams, but also two sides of his own desire, two sides of his own profound sexual hunger. And it means that everything under the play is just so volatile.

And I think often, too, these great plays — whether it's from ancient Athens or Elizabethan London or this — these great plays come at moments of huge historical change, often after major wars. And this play is a of flowering of that new America. It's the same time where the great Arthur Miller plays come as well. And in post-war America is a changing society that's becoming the kind of muscular empire we now see disintegrating.

And I think that everything in the play is really loaded. So it's about trusting that, encouraging the actors to access it. In this production, I guess there are a few structural things done, in that Blanche usually leaves the stage — and she does not leave the stage. She's briefly absent in the first minute, I think, before Stella runs out and then she arrives with the suitcase. And then she's very briefly gone the at the end. But even when she and Mitch go to the fairground or whatever, they're still onstage in this production.

So that was, I guess, part of also the compact with Gillian, was: what is it like to expose, to put every single moment of this woman's crisis under the microscope and not give her anywhere to hide? So, even during the scene changes, the costume changes between scenes, she's exposed and literally exposing herself while doing them, and she has to stay in that.

So I think it's also structurally thinking of the play as this last downward spiral of this, that's been going on for some time — maybe even generations within her family, and the legacy of slavery and corruption in her family. And then she's the last one left. She's the last queen of this ruined nation who comes into exile, into the camp of her enemy, Stanley.

And I think it's also been just about what that process in the rehearsal room is, and making sure that it's understood that every night they're going out there to chase it down. And when the play is big enough, then that process never finishes. They're going out to meet each other and the play and the audience afresh every night, and to play the game to the hilt."

On the Challenges of Live Theatre, and the Extended Run of Interrogating a Story and Its Emotions Night After Night That It Affords — and Andrews Once Saying That It and Film Are the Same Thing

"I'm not sure in the end they are the same thing, either. I think probably what I meant when I was saying that once is that they tap into the same place. And that that someone like [Ingmar] Bergman, who spent his artistic life moving between the theatre and the cinema and not making a binary between the two of them, but that they could be a conversation in which he's exploring ongoing questions — I think that is really, really an ideal for me.

But one thing that, of course, is entirely different is that cinema is made by a frame and a camera recording the world. And the shot of the poppy shaking in the garden, cut to the hand of the trembling actor, cut to something they say on their face: that creates the meaning, that creates the story, that creates your feeling. And you collect it during the shoot, but it is then cut up and reconfigured in the edit room, and that is the art and the architecture of cinematic storytelling. So the swaying poppy is just as important as their closeup on the actor's eyes.

In the theatre, whatever images there might be onstage or whatever — even if there's an emptiness onstage, even if the actor is absent, it's about the absence of that actor. The actor is everything in the theatre.

And it's where I come from first. It is my home and it is my emotional gymnasium. And it's this very beautiful, privileged space, like a little island where we go to reflect on the world and reflect on being human and reflect on being alive, to deal with emergencies and crisis — both political, personal, whatever — but within the permission of this safe room. So you can go into the places emotionally that would send you to the madhouse, like they do Blanche, or put you in prison like if you were to follow through with what happens in that room.

But it's a room where we then have permission to think through, play through, work through, together as a collective, without the big, beautiful apparatus — that was a Trumpian sentence — without the extraordinary apparatus that cinema has. You need, even if you're reduced, stripping it right down, it needs this village of people and technical equipment to make it. The theatre needs nothing in the end. Just a circle of viewers and the players.

And I guess as I then started to make — I made my first film just after Streetcar, I made Una in the months after Streetcar the first time — and as I've started to move more between the two mediums, I think it's become even more precious, this sense of the fragile, the gift of being in a room with people and exploring these things, but also the idea of this fragility and the idea that if I'm going to do theatre, I don't want to hide behind anything.

So my theatre was already pretty raw, but I think since then it's become even more about — in every show I've done since COVID and since my last movie, the audience has been lit. They are to a degree in Streetcar, but in recent plays like The Cherry Orchard, they're lit by this same forensic white light. You're very aware of them sitting there. The actors sit amongst the audience and step up and play from that.

So this essential liveness and this essential experiment of theatre, that it's a nightly process, an experiment, I think has become even more important to me — or, if you like, it's always there, it's always there in theatre, but it hides behind a lot of bullshit often."

On Whether Taking Either A Streetcar Named Desire or Cat on a Hot Tin Roof to the Big Screen as Films Appeals, as Andrews Did with Una

"Probably not with either of those. The Streetcar, the Kazan one, I'd rather film the play like this. I think it's different if it's a new play.

I think things have to undergo a transposition, right, and Una undergoes a significant transposition. It's not filmed theatre. You could even say some things that are closer to filmed theatre, like the Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? or something, still that makes a transmutation of form.

And so I think more, sometimes I think about two things. To take a story — and this is something I've talked to with some actors about; I've talked about it with Cate Blanchett, who's somebody I've worked with a few times, and also with Nina Hoss [Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World] separately, who, both of those who are great theatre actresses and great film actresses — this idea that if you've played a role in theatre, you've lived it so completely and you've explored it in so many different ways compared to [film].

This isn't comparative. I think they're both significant. But compared to filming for and performing for the camera, which is like you're doing these short little sprints — you're doing these little bits that are then cut up — but when you've lived it in the theatre, I think they recognise, the wealth of having done that, what it might mean to do that in another, to take all that, take the character, rewrite it for another form.

Weirdly, it happened when Cate had done Streetcar herself, right, for Liv Ullmann, and then did the Woody Allen film [Blue Jasmine]. She's sort of playing Blanche in that. And that's really interesting. To rather than say you're just copying the same thing, to say you grow a new creature from it, but using the same logic and ideas.

And then the other one that I'm starting to think about for a future project — and maybe this is because of the NT Lives. Like I said, they film them themselves and that's great, and they're really excellent things to have out there, and they reflect the moment of the theatremaking. But there's one where then I as a filmmaker and a theatremaker might take the production, and not make it as a film, like the Kazan version of Streetcar, but do my own cinema version of filming the production.

So like the Paul Schrader Mishima or something, right, which has that artificiality in it — but do bring the camera into the theatre space that's constructed, and make this boutique object from that. So I'm very curious about that. And I think NT Live proves that there's an audience for that as well."

David M. Benett/Getty Images.

On Andrews' Dream When He Was Starting Out as a Director Three Decades Back — and How Even Imagining NT Live Wasn't Possible

"No, I didn't. I mean partly, some of those things were impossible to even conceive of then. The world has changed so much.

Also, I think my ambition has always been of a different kind. I never began thinking 'oh, I would like to work in these places. I would do this'. I was always just obsessed with making work. So those first works in the Red Shed in Adelaide, they were all-consuming.

At the same time then, on the nascent internet or however, I was sort of Googling different — well, it was probably pre-Google — looking for radical theatremakers in the world. And in 1999, getting to travel and go and meet them and see their work.

So for me, it's always been a hunger for the work and about the work. And all of the opportunities that have come — right from, I guess, first going and working, being invited from Adelaide to become a resident at Sydney Theatre Company, then being invited to come and work at the Schaubühne in Berlin, and then going to London and so on — they have always come from the work, from somebody seeing the work, recognising the work and inviting me to build on that.

I've never looked and said 'I want to be working on these stages' or be there — other people work like that, but for me, it really comes from the work.

I think back then, I loved cinema very much and was very influenced by cinema, and thought that I would like to make a movie one day but was busy with theatre for a lot longer than I thought — and absolutely consumed with theatremaking, but I guess I always hoped that I would do that.

And to move between those two worlds — we mentioned Bergman — that still remains a goal. And to make a movie that can have the effect on people that Streetcar has, I don't think I've quite done that yet. That can be very, very true to itself — very true to itself — and also have audiences lined around the block to see it when we did it in London, and people still wanting to see it in the cinema.

I'd love to find that sweet spot in a movie, and I feel there's still a lot of work to do there — and that theatre is a place I can keep returning to for now. That's a really beautiful, safe home to explore in.

So it's always about the work for me."

NT Live's A Streetcar Named Desire returned to Australian cinemas from Thursday, June 19, 2025.

A Streetcar Named Desire images: Johan Persson.