This Year’s Ashes

Try as you might, you can't find closure in sauvignon blanc, the beds of strangers or cricket matches.

Overview

Imagine if the SBW Stables Theatre in Kings Cross were not the SBW Stables Theatre. Imagine if you climbed those creaky stairs and in place of one of Sydney's premiere performance spaces was just another of the area's utilitarian, asbestos-laced, '50s-era studio flats whose occupants are too unsettled to wholly furnish. Imagine if this flat, in this exact spot, held a story — of a young woman and her encounters with love, loss and cricket.

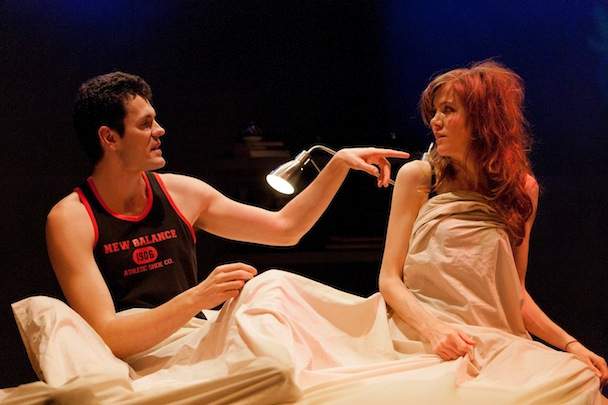

It's a slightly magic flat. Thick grass grows in place of some of the floorboards, and, on a few fuzzy mornings, a typically Cross-ian neon sign drops down to inform us, "This is not her place". Ellen (Belinda Bromilow), a Melburnian whose two years in Sydney have yet to bring friends or any sense of belonging, has taken to finding comfort in sauvignon blanc and the beds of strangers. They're all played by Nathan Lovejoy (an FBi Awards best performer nominee for Way to Heaven): Brian, an overeager Stanmore sharehouser; Tom, a pushy Woollahra work contact; Adam, whom she has accidentally brought back to her own place and ought to remember from somewhere. At the same time, her father (Tony Llewellyn-Jones) has emerged as a surprise house guest, and she regresses to childlike vulnerability and desire to please as they follow the summer's Ashes cricket matches — on the radio, as per their tradition.

Some say there are five stages to grieving. There also happen to be five tests that make up the Ashes. It's one of the most beautiful and yielding of this play's devices. The result is moving but graced with plenty of gentle humour — This Year's Ashes is proudly a romantic comedy, and it uses that generally derided genre's conventions to question as well as entertain. The new work is inspired by playwright Jane Bodie's own experiences struggling with a relocation back to Sydney, and the honesty embedded in it shines through.

The shine is dulled somewhat by moments of melodrama, which do not work in the play's favour and are amplified by lighting, sound and directing cues that try too hard to tell you how to feel (much like a mainstream romantic comedy would, come to think of it). It may be why the scenes between father and daughter don't quite knock you for six.

There's also that niggling reason why we don't often see modern romantic comedies on stage: the genre is built on fantasy (true love will rescue you, conquer all, etc, etc), and art, we often think, is for seeking out truth. That's not to say you can't go fossicking with such a tool and still unpick nuggets of trueness, but this outing could have come back with a heftier haul.