Mia Madre

In attempting to replicate the chaos of grief, this Italian drama bites off more than it can chew.

Overview

Italian filmmaker Nanni Moretti is no stranger to death, or to examining the subject on film. It might be something most of us don't like to think about, however the writer-director understands the shadow mortality can cast, as well as the way that the act of mourning can overtake a person's life. After exploring the impact of losing a child in 2001's Palme d'Or winner The Son's Room, and then writing and starring in 2008's Quiet Chaos, he returns to the topic with Mia Madre. That the film's name means "my mother" in his native tongue is telling.

Taking a decidedly meta approach, the film follows a filmmaker in the midst of production while at the same time coping with the hospitalisation of her mother. It's not quite as autobiographical as it sounds: the director is a woman, Margherita (Margherita Buy), while Moretti plays her brother Giovanni, and veteran Italian actress Giulia Lazzarini plays their mother. And yet, in the way that Mia Madre hones in on the stress of simultaneous professional and personal crises, there's no doubting that the tale evolves from experience.

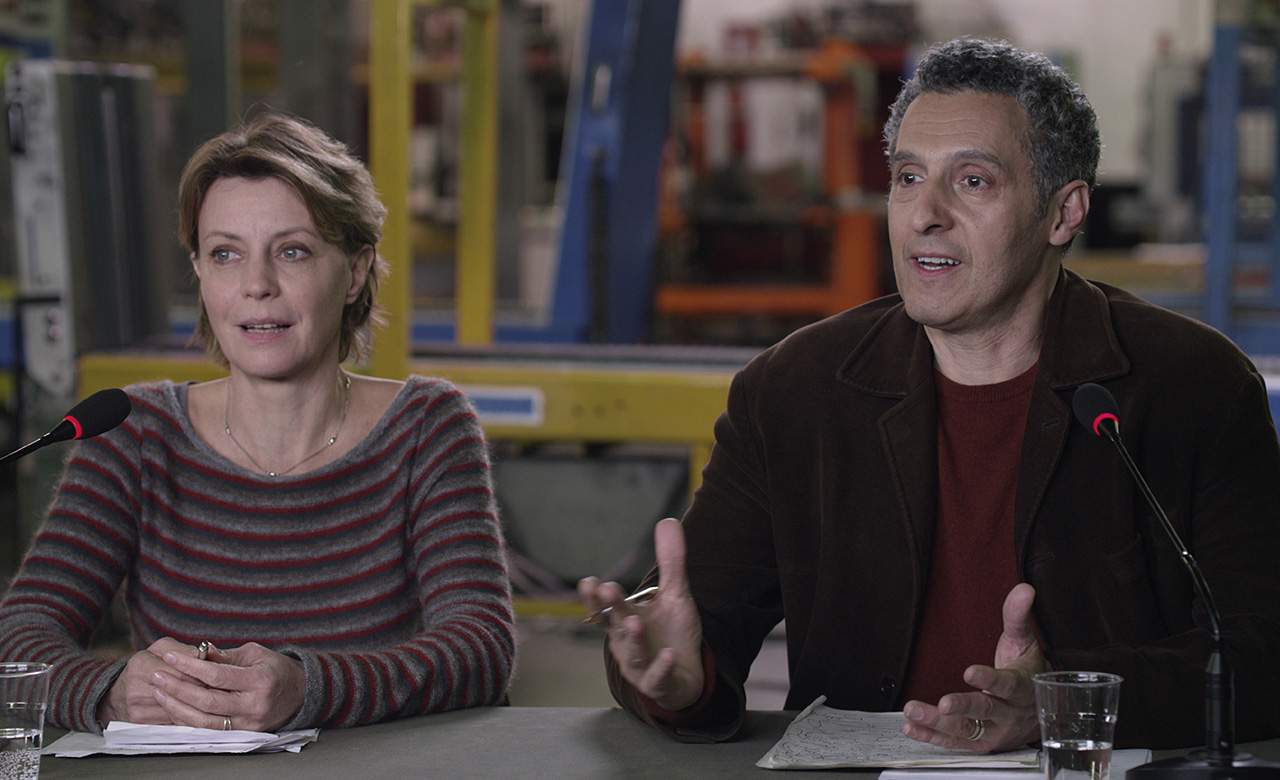

As her mother's health begins to decline, Margherita struggles to make her movie – about factory employees fighting for better working conditions – while also using it as a distraction from her troubles. Alas, her freshly arrived American lead (John Turturro) refuses to learn his lines or follow her directions, constantly derailing and delaying production. With her live-in lover in the process of moving out and her teenage daughter struggling at school, Margherita's home life offers little solace either.

Depicting many a balancing act, Mia Madre swiftly proves one itself. Moretti keeps searching for the right mix between quiet and anxious, dramatic and comedic, and contemplative and freewheeling. In fact, his film is more convincing in demonstrating how frustrating that can be than it is in finding any harmony between its competing elements. Of course, that's partially the point, with grief clearly painted as a disruptive and destabilising force. And yet, as accurate and authentic as the movie's messiness feels in an emotional sense, it also makes other contrasting factors — such as the patient camerawork and energetic performances — seem slight, a little convenient and sometimes out of place.

Indeed, it's always distracting when a specific actor appears as though they're in the wrong film, even when they're one of the best things about it. Turturro lights up the screen and brings a few well-timed comic moments, yet never completely fits in with his surroundings. That's not a criticism of his performance, or of the more restrained but similarly excellent efforts of Buy and Moretti. Instead, it's an acknowledgement that even in thoughtful, intimate accounts of something as complex and challenging as death, mimicking chaos and actually embodying it aren't quite the same thing.