Moulding Life's Ups and Downs Into Moving Stop-Motion Animation Masterpieces: Adam Elliot Talks 'Memoir of a Snail'

No one makes movies like this Australian filmmaker, who returns to cinemas with his second feature-length clayography 15 years after 'Mary and Max'.

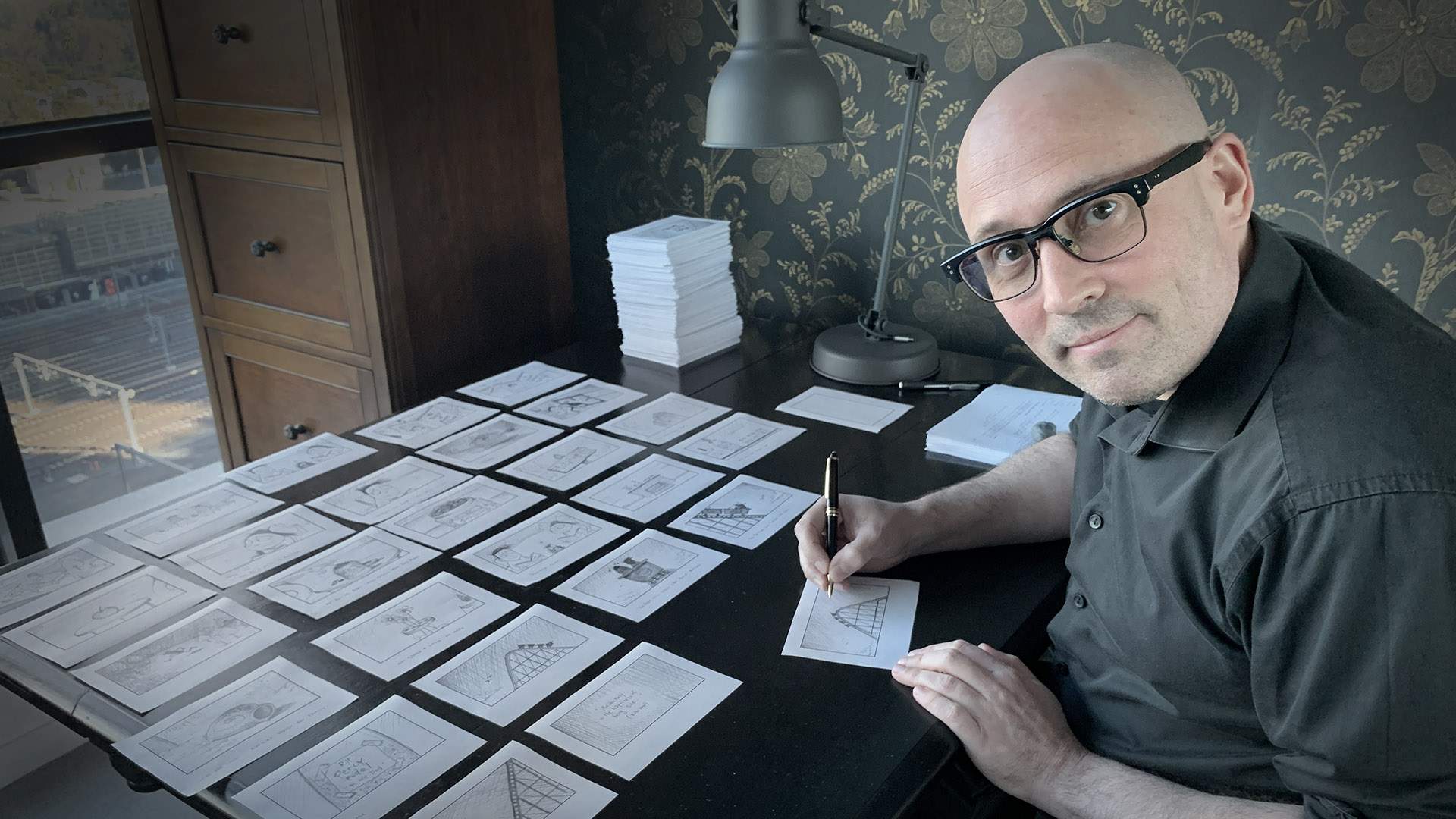

Although it's impossible for viewers to tell while watching it, as over 7000 handcrafted items that took around 20 different artisans 48 weeks to make bring Memoir of a Snail to glorious life — pieces that were used to animate the film's 310,000 individual movements, too — Adam Elliot's latest feature Memoir of a Snail is the result of compromises. Every movie by every filmmaker is, of course. Existence in general is a series of bargains and trade-offs anyway. But the Australian animator's output is so distinctive, so clearly the product of its guiding force's vision, and so deeply moving in its balance of laughs and darkness, that each one plays like it's been lifted from his brain wholesale.

It has almost been three decades since Elliot first made stop-motion magic with 1996's three-minute short Uncle, starting what he's dubbed a trilogy of trilogies. The plan: to make three short shorts, three long shorts and three features, all using his instantly recognisable style of animation. The fondness for brown and grey hues, the hand-moulded appearance of each clump of clay, the intricate character studies that see the ups and downs that life takes us all on: they've all continued through his two other short shorts, 1999's Cousin and 2000's Brother, and then in his lengthier efforts.

2024 marks 21 years since Elliot initially went slightly longer with the 23-minute Harvie Krumpet — and two decades since he earned one of filmmaking's highest and most-coveted honours, taking home the 2004 Academy Award for Best Short Animation. Then, six years later, came his debut feature Mary and Max, which continued adding to what's now a swag of more than 100 career accolades. The 21-minute Ernie Biscuit followed in 2015, but Memoir of a Snail arrives 15 years since Elliot first ticked off that debut full-length effort. It too has been boosting his prizes. Upon its premiere at the prestigious Annecy International Animated Film Festival in France, it was named the fest's Best Feature. At the London Film Festival, it won the event's 2024 official competition.

Memoir of a Snail also opened this year's Melbourne International Film Festival — aptly given that Melbourne plays a key part in its early scenes — on its many fest stops around the world. Unsurprisingly, it's been a whirlwind few months for Elliot when he speaks with Concrete Playground about the movie. "I think this is my seventh film and each one feels like a birth. You just want to make sure the baby has all its fingers and toes, and it's a pretty baby, and no one thinks it's ugly. So it's this sort of very precarious nerve-wracking period. It's no different for any other filmmaker. It's stressful for several reasons. It's not just 'will the film work?', but 'will I have a career to continue on with?'," he advises.

"But, I have to admit, not that I had low expectations, but our budget was so much lower than Mary and Max — and so we couldn't afford walking, so we had to do the Muppet technique, and there was a lot of compromises. Everybody worked on award rates. So I didn't think it would be as well received as Mary and Max, but it's still early days, but it seems it seems to be getting a better response than Mary and Max." Elliot continues. "I do find the pressure and the expectation with each film gets greater and greater. I mean, you try to block that out. But the reactions are very consistent. France, then Telluride Film Festival, Melbourne Film Festival and Spain, San Sebastian. And even with the language — France and Spain had subtitling — most of the jokes, excluding Chiko rolls, most of the jokes were understood. So that's a big relief. I think the word 'relief' is probably the word I've been using the most for the last couple of months."

With Succession star Sarah Snook leading the cast — and Eric Bana (Force of Nature: The Dry 2), Tony Armstrong (Tony Armstrong's Extra-Ordinary Things), Nick Cave (The Electrical Life of Louis Wain) and Magda Szubanski (After the Trial) among the others loaning their voices — Memoir of a Snail tells another of Elliot's outsider tales, focusing on the lonely Grace Pudel. The film unfurls as Grace's reflection upon her life, from her childhood in Melbourne with her fire-obsessed twin brother Gilbert (Kodi Smit-McPhee, Disclaimer) and their widowed father Percy (French actor Dominique Pinon, The Walking Dead: Daryl Dixon) onwards, as told to a snail named Sylvia. The movie's protagonist has long loved garden molluscs, literally wearing her love for them on her head. She's also largely been happy in her shell, until she meets and befriends the elderly Pinky (Jacki Weaver, Hello Tomorrow!).

Elliot coined the term 'clayography' to describe his films, which use his preferred medium to unpack rich stories about his chosen characters — figures that spring from real-life tidbits gleaned from a lifetime love of observing others. The folks in his frames are as detailed and idiosyncratic as anyone living and breathing, and his movies have always proven deeply resonant as a result. We also chatted with the writer/director about his process of building characters, and finding that mix of humour and heart. Similarly part of our discussion: Elliot's initial animation and filmmaking dream, the path to Memoir of a Snail, his approach to writing, casting the movie and more.

On Elliot's Initial Animation and Filmmaking Dream — and How Everything That's Come Since Stacks Up Against It

"Well, certainly an Oscar was never even in the realm of something I thought would happen, mainly because I thought my films were too arthouse or boutique, or for adults. I never have had a strong long-term ambition. I did come up with this pretentious idea of doing a trilogy of trilogies: three short shorts, three long shorts and three features. I never thought I'd be up to number seven, so I've really only got two left and then I can die.

I think I was very surprised at how universal the films have become, and that they haven't really dated. I still get people who have seen Harvie Krumpet for the first time sending me emails.

And I'm constantly aware of and surprised by how people's suspension of disbelief, how they really do invest themselves in these plasticine blobs. It's hard for me to be objective. I've got a friend who's a GP and she just can't watch animation. She can't pretend to believe these characters are real. I think it's quite humbling to know that people really do give over to the characters and their stories.

I thought at this point in my career that maybe stop-motion would be an artform that had disappeared. I was told that when I was at film school — I was told that stop motion was a dying artform and CGI would kill it, but the opposite has happened. Stop-motion is going through a bit of a renaissance or a golden period, and there's a lot of reasons for that, but it's alive."

On the Path to Memoir of a Snail

"I don't want to refer to Woody Allen, but I will. I've always liked his methodology of just finishing one and going straight into the other, and not getting caught up in the hype and the buzz. And, of course, you have to do promotion as an auteur. And you are part of the marketing campaign and strategy by Madman and the distributors and sales agents.

But I'm thinking to the next film, and you've got to practice what you're preaching. In Memoir of a Snail, I'm always talking about moving forwards, moving forwards — and it's literally back to the drawing board. I'm starting to think about the next characters. What are they going to look like? And more so narrative and the story and what type of film I want to do next.

I'm one of those lucky few filmmakers who hasn't had to revert to TV commercials or TV series or other forms. I've been very lucky that Screen Australia and the state funding bodies, VicScreen here, perpetually fund me. I know I'm lucky. And I know we're lucky in Australia, even having government support. So, I remind myself that quite often.

Having said that, I'm always prepared to criticise the funding bodies because I think they could be doing more. I'm very annoyed they no longer fund short films.

I do also worry, just quickly, that each film has a lot of references to previous films I've made, and there's a lot of repeated motifs I bring back. And I do start to worry my films are becoming formulaic and repetitive. I know somebody in IMDb posted a comment 'Adam Elliot's films are all the same'. They're right."

On Elliot's Entry Point Into His Films and Approach to Making Each One Stand Out From the Rest

"I do start each screenplay, I have to wait until I'm agitated by something or frustrated or extremely curious. And this film, I was going through the death of my father, the grieving process, and also getting rid of all his stuff. He had three sheds full of stuff, so I became fascinated by that.

So I do a lot of research. I'm a very slow writer and I have to be enthused and driven by something. I can't just force myself to sit down and write. And sometimes it takes a few years. But when I do start the writing process, I really do become obsessed with it, and I love rewriting and writing. I mean, I could just do endless drafts. I never really ever want to start making the film. I just want to keep writing.

I try to create films that I don't see and that deal with subject matter you don't see. And not that I'm trying to shock or deal with taboo subject matter, I just feel that there's things — there shouldn't be rules to animation. I don't want to offend, but I get annoyed when people think that animation is a genre. It's not, it's a medium.

There was someone in the audience last night, who was talking about 'oh this film's not for the young children'. The onus is not on me. The onus is on the parents. The film's rated M. And I never get this problem in France and Germany, when I go. They have a long history of adult animation, particularly in countries like Estonia and the Czech Republic, there's a lot of surrealist animation.

I think it's a job of a writer and a director to push the boundaries and push themselves. I'm very self-conscious of not just becoming stale. And if the artform of stop-motion has got to survive, it's got to move beyond Wallace and Gromit. It's got to move beyond family-friendly. And there's certainly many other stop-motion artists out there who would love to sink their teeth into an adult animation or an abstract stop-motion film, or an experimental.

But of course, the thing that prohibits all this is money. It's a very slow, therefore very expensive art form. And again, I'm one of the lucky few who — every year, there's probably only three or four stop-motion features made. There's only been three in the history of Australian cinema and I made one of the others, Mary and Max. So we're very, very rare."

On Finding Inspiration for His Characters in Real Life

"I'm self-diagnosed OCD. I haven't had a clinical diagnosis, but I know I am. I'm very, very, extremely neat, and I obsess about detail. And I start with the detail and work backwards. So I don't worry about the three-act structure and the plot and the narrative until much later. I just gather all my ingredients — and I have very detailed notebooks going back decades.

I collect quotes, I collect names, I collect sounds, I collect smells. I'm a hoarder of words, I suppose. And I just love going over my notes, and there's so many that I've forgotten that I've written. I also have very long descriptions of people I've just seen on the street.

And I invent stories. I write poetry. I went through a period during COVID where I would write a poem every morning before nine o'clock. And so if I ever lost these journals, I wouldn't know what to do because they're my recipe books. It's where I get all my ingredients.

I love observing people. I'm always staring at people on public transport. Even today, on the plane, I got caught staring at someone, so I'll probably get arrested, too.

'Why are they wearing those shoes? Why did they choose those earrings? I wonder what their backstory is.' I love backstories. Pinky has this whole backstory that no one will ever know about. It's mentioned briefly in the film, but to create very dimensional characters, I think you really have to go into every layer and dimension of them — because I'm aiming to create authenticity and believable characters. To give them dimension, you have to give them incongruities and contradictions.

And it's not a matter of just pinning the character full of all these quirks. They have to be human. They have to have contrast and contradictions. So I'm certainly character-driven more than I am plot- and narrative-driven.

On Elliot's Casting Process, Knowing Sarah Snook Was Perfect for Grace and Getting Lucky with Tony Armstrong

"Well, I collect voices as well. So I have long lists of people who I think have fantastic voices for animation, or I might be able to use in the future. So I had listened to Sarah's voice, one of her early films, These Final Hours, when she was just starting out. There was the quality I loved. There was a quietness and vulnerability about her voice. So she was in my head very early on.

But I did then listen to the Blanchetts and the Kidmans and the Wilsons and all the others, but none of them really ticked the boxes that Sarah did. But there's always a danger, too, that you might have this fantastic voice and then the animators do some lovely animation, and you marry them together and it just doesn't gel for generally an unknown reason.

A good example is the very first Paddington film, five or ten years ago, was originally going to be Colin Firth. And they paid him. They cast him and they put his voice to the animation, and it didn't work. So they had to let him go and then in the end, they got Ben Whishaw — and he works beautifully as Paddington.

So you never know. And you certainly don't want to have to tell an actor 'sorry, your voice doesn't work'. But I'm very intuitive and I also love non-actors. I do like getting people who — for example, Tony Armstrong, we'd already animated Ken, and I just couldn't find the person I wanted to voice Ken. And then I was watching ABC News Breakfast and Tony came on. And not only did he look like Ken, but he had that bass to his voice, that suaveness. And I thought 'oooh, I wonder if he can act?'.

So we got in touch. And my gut instinct was actually he'd work. And it did. But sometimes you can get it wrong. And also, too, with casting, they're not the actors — the actors are the animators.

I always remind the actors — I call them my voice, they're loaning us their voices, really, that's what they're doing. And they get paid a lot of money for only a few hours work. So you've got to make sure when they're in the studio, you get exactly what you want. So I do work my actors, my voice talent, quite hard, and we do many, many takes."

On Filling Out Memoir of a Snail's Voices with an Australian Who's Who

"It ends up being quite eclectic, and luckily we don't have to cast everybody upfront. So we only cast the voices where there's lip-sync. So it's quite leisurely in a way. My producer and I, Liz [Kearney, Sweet As], had a lot of time to go through every casting book and listen to every voice. We listened to everybody from Jimmy Barnes through to politicians.

Then in the end, I did some of the voices, Liz did a voice. It's just a lot of experimentation, actually — a lot of just closing your eyes and listening, and watching some clips of animation.

Certainly we got our dream cast, I have to be honest. We got pretty much everyone we wanted and thankfully it all worked out. But as I say, it's risky, and sometimes it goes pear-shaped."

On Balancing Lightness, Laughs and Hope with Melancholy and Tragedy to Make Audiences Both Laugh and Cry

"It's the thing that keeps me awake at night, is the balance, and it has been from day one. I often think 'gee, Adam, why don't why you just doing children's TV?' or 'why are you doing something like Bluey?'. Although Bluey has wonderful darkness at times as well, and is very clever. But yes, it is a balancing act and you don't want to depress the audience.

I read somewhere, someone, I think it was on Letterboxd or somewhere, said 'Adam's films are all trauma porn'. And I thought 'oh gee, maybe they are'.

I'd hate for my films to be called bleak. There's a lot of bleak Australian cinema. I do try to instil moments that are uplifting — and particularly my endings, I really want the audience to come out of the cinema feeling satisfied and relieved.

They might be melancholic. I love that Victor Hugo quote that melancholy is the happiness of being sad. And I wouldn't say my films are sad films, they're melancholic at times, but ultimately I'm trying for them to be life-affirming and uplifting and soulful. A word I use a lot is 'nourishing'. I really want to nourish the audience. What's that horrible quote? Chicken soup for the soul.

I think that's what I'm ultimately trying to do, it's empathy, that I'm trying to get the audience to put themselves in my characters' shoes and understand what it's like to be someone with a cleft palate. Or someone who, with Mary and Max, somebody who has Asperger's syndrome, who's being bullied and teased.

Bullying and teasing is something that is a thread that goes through all my films, and that's because I was bullied and teased. And in some ways, my films are not revenge but they say to the bullies 'what you do is incredibly hurtful and destructive, and there's a whole lot of us out there who've had to carry this with us our whole lives and deal with it, suffer the consequences'.

And I think there's so much animation out there doing other things, pure entertainment. I don't like getting lumped in with adult animation such as South Park and Family Guy. They are adult, but they're different, they're not trying to do the same things I'm trying to do.

I do feel often very alone with what I'm doing. I'm surprised there aren't more people doing what I'm doing. I think there's certainly a demographic out there. There's certainly people who really connect with the works. I often get emails — I got an email the other day from a woman who has a cleft palate saying it's the first film she's ever seen that dealt with someone having a cleft palate with sensitivity and truthfulness.

So you realise as a director and a writer that you have a degree of responsibility, and that films and cinema, they have a longevity, but they also can have an impact. I wouldn't say we save people's lives. I wouldn't go that far. But it's taken me a long while to fully understand that you can have an impact, and so you better be very mindful of that and be careful what you say."

Memoir of a Snail opened in Australian cinemas on Thursday, October 17, 2024.